When the coronavirus struck, hospitals around the world faced a crisis like no other. The knock-on effect is likely to be as catastrophic, with delays to cancer, heart and stroke services as well as patients avoiding treatment altogether in a bid to stay away from Covid-19 hotspots.

We’re already seeing the impact: Globally, millions of women have missed breast cancer screening appointments because of paused services during the height of the pandemic in March and April. This means thousands of cancer cases could lie undetected and the diagnosis delayed, say breast cancer charities.

In Kenya, where breast cancer is the most common type of the disease, the picture is equally alarming. Across the country, the uptake of cancer screening services when it’s offered is eye-wateringly low.

Last year, only 1% of eligible women were screened using mammography, the X-ray test used to spot cancers at breast screenings, despite equipment being available in most county referral hospitals (cost, awareness and enough knowledge to operate the machine all play a role). Only a quarter of women aged 14 to 49 say they have conducted a self-breast examination, and 14%t have had a doctor or healthcare provider carry one out, according to the Kenya Demographic and Health 2014 survey.

Advanced stages

And this was before the pandemic. Now, the number of women receiving check-ups or screenings is even lower, says Dr. Miriam Mutebi, a breast surgical oncologist and Assistant Professor of Surgery at Aga Khan University Hospital. When more than half of cancer patients in Kenya are diagnosed at advanced stages — and there’s fewer than 50 oncologists for a population of 54 million — it becomes all the more important for women to be able to spot any early warning signs.

We spoke to Dr. Mutebi about the challenges she’s seeing and why now, more than ever, a breast self-examination might just save your life.

What impact has the pandemic had on breast cancer screenings and treatment?

Unfortunately, we’ve taken a hit. During the lockdown period, many patients couldn’t travel into the city or were a little stranded in terms of accessing care or treatments. Now, I’m seeing a number of people who found a lump back in February or March but are only just coming into the hospital now.

Initially, there was so much uncertainty and confusion around the Covid-19 rules. I think the message that a lot of people received was; you go to the hospital, you get the coronavirus, you die. A lot of people just thought: “I’d rather wait.” Towards the end of July, patients slowly started to come back, but it’s worrisome. In the oncology community, we talk a lot about how COVID-19 has pretty much stopped everything except cancer — the cancer cells are still growing.

What kinds of cases are you seeing?

It’s a mix. We’re still seeing people who find a lump and come in within days or weeks. But quite a number of patients are coming in when the disease is more advanced, and they need something called neoadjuvant chemotherapy upfront, which is used to try and shrink the tumor ahead of surgery. I’m also seeing more and more cases where the disease has already spread to different areas of the body.

This trend is unfortunately likely to continue, especially with a potential second wave. People are still concerned, and again not traveling to Nairobi and other major towns where most of the main breast cancer services are located. For patients who live outside the capital and have received a diagnosis, I try to redirect them to the closest healthcare facility where they can get treatment.

You mention redirecting women — what are some of the barriers to accessing treatment?

Pre-COVID, one big barrier was that patients would need to routinely travel several hours to access radiotherapy at the main referral hospital in Nairobi. And radiotherapy isn’t a one-off. You’ll likely need at least three to four weeks’ worth of treatment and you need to pay for accommodation in a strange city. Quite a number of people say, “you know what, I can’t afford this.” If we’re able to bring these services closer to patients, that’s a huge win.

Regarding screening and early detection, one of the major challenges we are trying to address is health-seeking behavior. Often the thinking is; ‘there’s nothing wrong with me, why would I go looking for trouble?’ The message we’ve been trying to get across is, paradoxically, if you go to a screening and find something, that’s the stage you want to catch it. Not only is it treatable then but potentially curable, too.

Socio-cultural barriers are also relevant. Women may rely on a partner or spouse for support and in some cases permission, to access care, which translates into delays in diagnosis and treatment.

And the cost, too?

Unfortunately, patients are still having to pay out of pocket. The National Hospital Insurance Fund (NHIF) helps to cover some of the care and treatment fees, but it currently doesn’t stretch to mammography, which can cost between Sh1,500 and Sh6,500. That’s a huge sum for lots of people and means the cost of screening for and treating cancer remains out of reach for many households in Kenya.

The National Cancer Control Program (NCCP) has just started to disseminate country specific screening and early detection guidelines. But there is no established national breast cancer screening program — and a lot of what we do is opportunistic screening.

During October’s Breast Cancer Awareness month, for example, extra screenings are often available and there’s an uptick in women going for check-ups. It helps that most of the major hospitals in Nairobi will drop their mammogram prices during this month, and NGOs will offer free or subsidized clinical breast exams or other screening services.

Screening is not an end point in itself. It’s what happens next that counts. It would be incredibly cruel to tell women: “we’ve found a concerning lump — you figure out what to do next.” Screening and early detection must go hand-in-hand with strengthening health systems to better support the entire spectrum of diagnosis, treatment and survival rate of cancer patients.

Does this uptick in awareness reach women across the country?

No, this represents a very small fraction of the population. The average woman in the rest of Kenya is not necessarily going to be like; “hang on, I need to get my breasts checked.” That’s why it’s critical to strengthen the outreach for these screening and early detection services on a primary health care level — people should be able to access these services without traveling to a large hospital or an urban area. Any woman visiting her local health centre for an antenatal check, or family planning clinic, should ideally be able to have a clinical breast exam and discuss breast awareness with a trained nurse or healthcare provider.

Why is it important for women to be checking their own breasts?

A lot of referrals come from women themselves – they’ve detected a lump and decided to get it checked out. The self-breast exam is part of a wider breast awareness strategy — being aware of your breasts and any change — and it’s definitely one of the tools that will aid in early detection. The earlier the condition is found, the better the chance of surviving it (and you’re less likely to need to have your entire breast removed). We want to give women the tools to be aware of their breasts and empower them to take charge of their own health.

How to do a breast self-exam in 6 easy steps

by Dr. Miriam Mutebi

Look

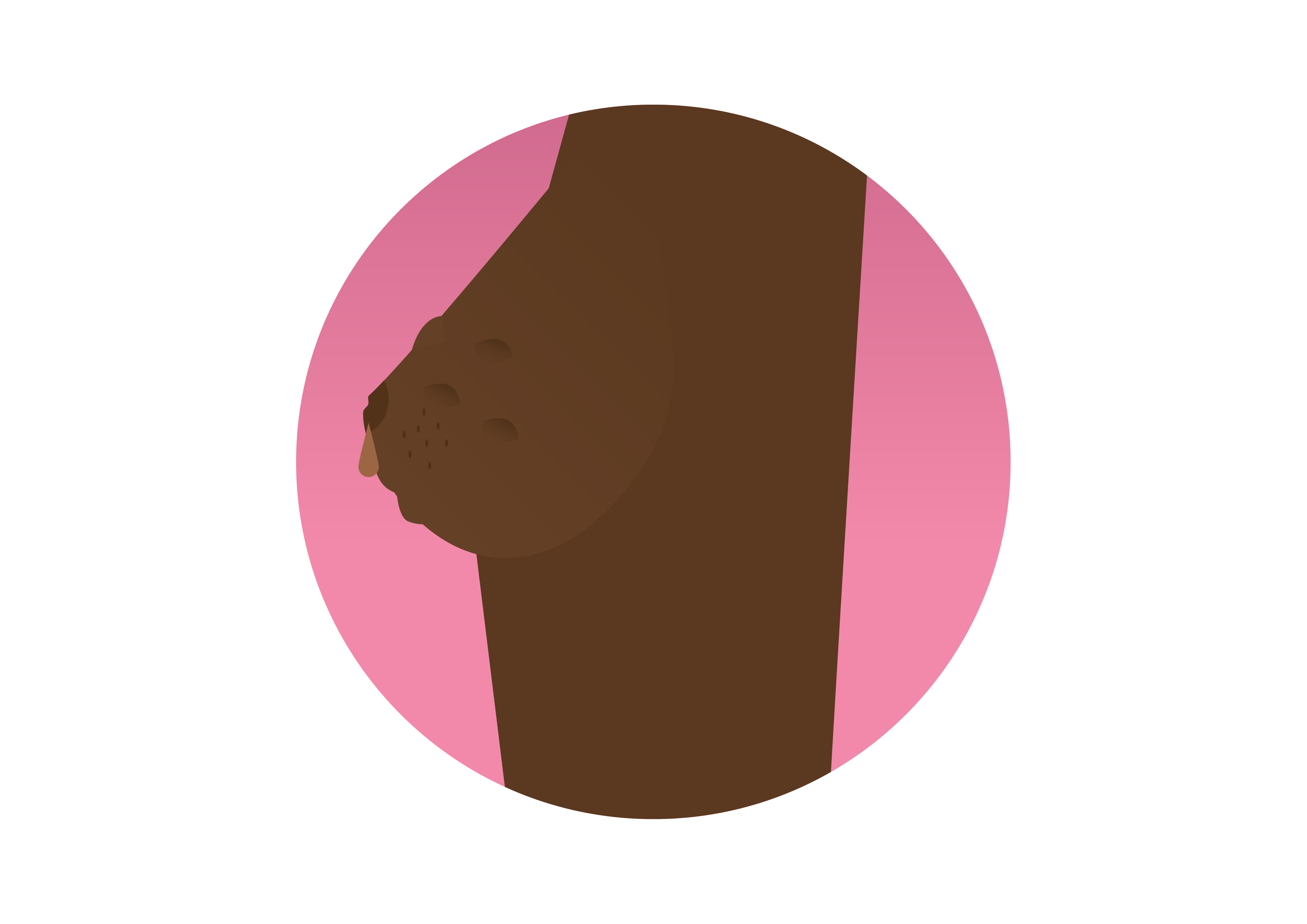

2. Check for any skin changes; any lumps, swelling, dimpling or thickening. Check for any changes in the nipple; discharge or a nipple that looks like it’s getting inverted/being pulled inwards (and wasn’t before) should raise alarm bells. (Sarah Ijangolet/The Fuller Project)

Move

Feel