Editor’s note: A version of this story was published on NBC News.

For more than a year, the coronavirus has flooded the world in successive, devastating waves, leaving grief and gaping loss in its wake. India is still reeling after a second surge of the virus hit the country in March this year. Researchers have estimated that at least 5 million may have died, according to Bloomberg News. The trauma that comes from hearing the constant whine of ambulance sirens, working to save lives, watching funeral pyres burn nonstop in the distance, and fielding panicked calls from neighbors and friends is profound and specific. As with any disaster of this magnitude, the most marginalized groups bear the brunt, women among them.

In America, the wide availability of vaccines brought hope. But many remain unvaccinated, and the threat of another surge caused by the highly contagious delta variant still looms on the horizon.

Related coverage: Gasping for Breath: Women Provide A Glimpse Into India’s Covid Disaster

According to researchers, this dangerous strain could drive an increase in deaths this fall that could take America back to where it was a year ago. Those in the U.S. with ties to India have to reckon with dual, interconnected realities: grappling with uncertainty and fear for themselves and those immediately around them, and for those loved ones across the world.

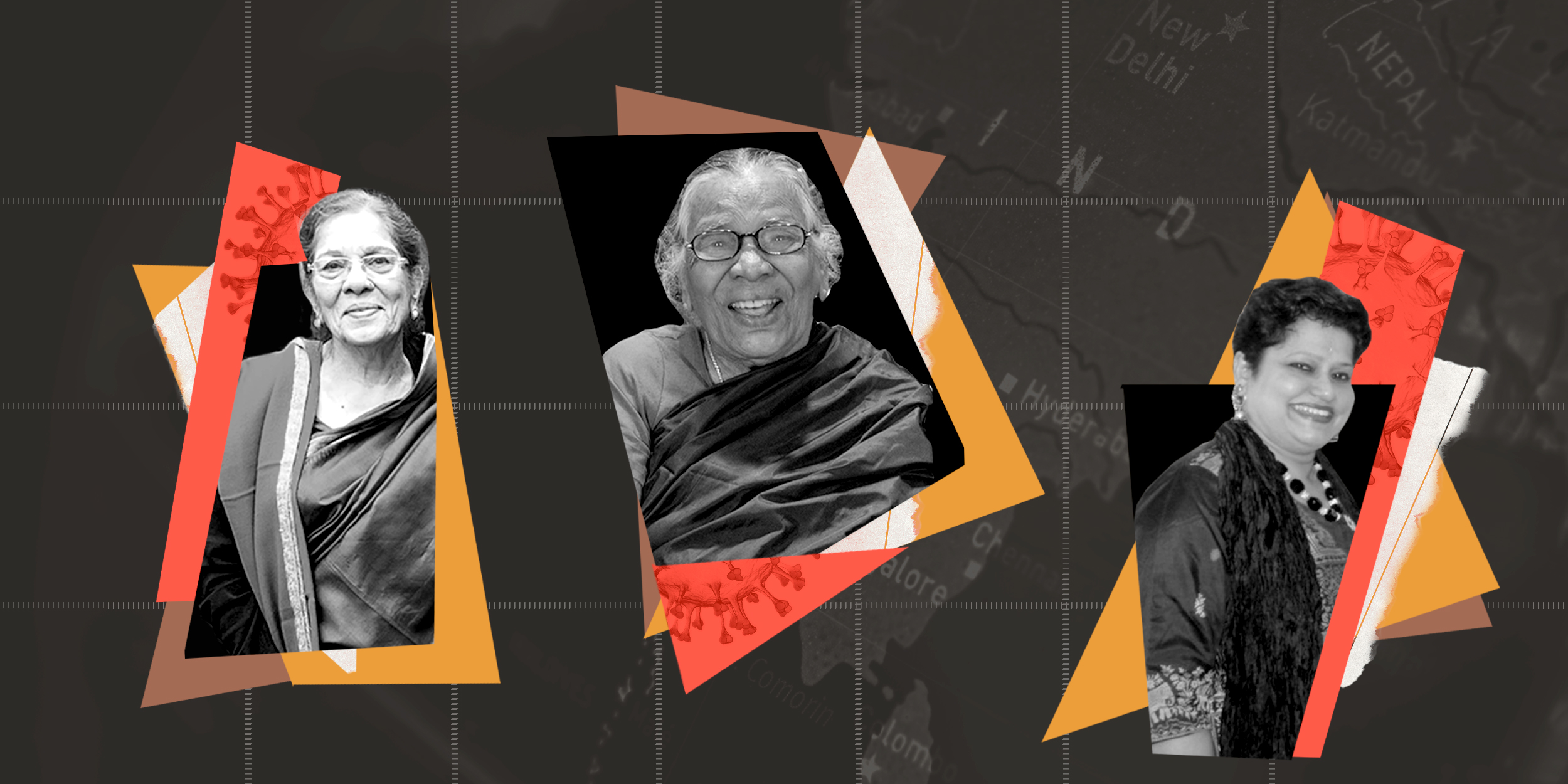

NBC News and The Fuller Project asked Indians in America to share tributes to female friends and family back home who have been touched by COVID-19 in some way. Below are stories of five such extraordinary women who either died during the pandemic or had their lives greatly affected by it.

Benson Neethipudi remembers his grandmother Manimma Kambham

The last time Benson Neethipudi saw his maternal grandmother, Manimma Kambham, in person was at his wedding in January 2020 — just before the pandemic hit.

She was dressed up and jubilant. He remembers joking with her at the time: “Till now you were saying: ‘Will you get married before I die?’ and now that we are getting married, you’re saying ‘When I die, will you come?’ You can’t keep pushing the goalposts.”

Kambham celebrated her 83rd birthday on March 1, and then two months later, on April 29, she died of cardiovascular arrest in Gannavaram, a small town in the Krisha District of Andhra Pradesh. It was at the height of India’s second Covid surge and strict protocols had to be followed.

Kambham had been a quiet fighter all her life. She lived in the shadow of her much more famous husband — the late K.G. Satyamurthy, a leftist, anti-caste revolutionary and literary figure. Satyamurthy started a guerrilla group that sought to overthrow the elite and was wanted by the local authorities. He ultimately went into hiding for many years, leaving Kambham behind to raise their kids on her own.

Living as a Dalit woman alone in a village without a husband was no small feat. In Indian society, Dalits, formerly labeled as “untouchable” according to the caste hierarchy, are subject to individual and systemic dicrimination, exclusion, and violence. Women are vulnerable to sexual attacks by upper-caste men. To feed, clothe, and educate her children, she herded buffalos and worked as farm labor.

“You just fight, you have to project that persona of being tough,” Neethipudi said of his grandmother. “So I have always wondered, if with her grandchildren, she was that soft person because she didn’t have the opportunity to be soft with her children.”

“That gentleness she showed to her grandchildren? Perhaps it was something she might have wanted in her life, but she could not get it,” he added.

After learning of Kambham’s death, Neethipudi’s mother, a retired doctor, along with her other siblings tried to make funeral arrangements at the local Christian cemetery where her mother wanted to be buried. But, with COVID-19 burials increasing around them, the cemetery had run out of space. They had to ultimately dig a new grave in the same plot as that of Kambham’s son, who had died a few years prior.

Neethipudi, a recent Columbia University graduate who lives in New York City and works as a public sector consultant, could not be there — he tried to witness the last rites via a grainy, halting video on Whatsapp.

“It was all logistical,” said Neethipudi. “They barely had the time to grieve, it was all about trying to get things in order.”

Neethipudi feels that both his grandmother and his mother chose to become buffers between him and a world hellbent on breaking them. And they did it without pomp or ceremony.

“For me to be able to be successful at this level is because my grandmother and mother chose to be those absorbing elements of trauma,” Neethipudi said. “And they never passed the trauma to us — or, they tried their best not.”

Lata D’Mello remembers her sister Sudha Manjrekar

Growing up, Lata D’Mello mimicked everything her older sister Sudha Manjrekar did. She wore the same clothes, adopted the same mannerisms, and embraced the same friends. “So my mother would joke: ‘Oh my God, I hope you don’t decide to want her husband as well!’” D’Mello said.

As adults, the two sisters forged distinct paths. Manjrekar, a teacher, got married and had two children in India. D’Mello migrated to the United States in the 1990s and now works in Iowa City, Iowa, as a program director of an organization serving Asian survivors of gender-based violence. She never married, but became a second mother to her niece and nephew — Manjrekar’s children — when they later moved to America for higher education.

In April, during the second COVID-19 surge in India, Manjrekar contracted the virus when she was visiting relatives. By the time she was transferred to a hospital with an available intensive care unit days later, her condition had regressed. She died of a heart attack on May 6 at the age of 63.

D’Mello recalls fondly the time they spent together when she traveled back to India — the sisters loved theater and would line up a marathon of local plays to watch. On such a visit a few years ago, they strolled down Mumbai’s Marine Drive after a date at the theater. As they walked hand-in-hand, taking bites out of their roasted street corn, they joked at how they blended into a steady stream of romantic couples trickling through the promenade.

Like their love for theater, their shared passion for social justice was passed onto them by their father, who fought against British colonial rule. But unlike some “freedom fighters” of eras past, Manjrekar was no ascetic. She loved to shop and would regularly doll up for outings, nails freshly done and lips bright with color.

She was a diva, said D’Mello, who would lightly tease her sister for these indulgences, only to get a quip in return: “She would be like, ‘Oh, no, not like you, dressed raggedy that way,’” D’Mello said.

D’Mello could not go back to say goodbye because of travel restrictions and because her family discouraged it. Instead, she flew to California to be with her niece and nephew in an informal long-distance vigil. Manjrekar’s clothes and jewelry still retain her distinctive scent, D’Mello’s other siblings tell her.

“She was 63 years old and she was looking forward to doing so many things, so I’m angry that she missed those opportunities… but it’s not an anger directed at anyone,” she adds. “I have a general anger towards or critique of governments that do not take care of their own and demand that people vote for them.”

Back in Iowa City, D’Mello has thrown herself into her work. But she is unable to engage in activities that remind her of her sister — like shopping, or listening to old Bollywood songs about sisterhood, love, and destiny. “I can’t even think of her as someone who used to be,” D’Mello says. “Even though I am very often practical, and fatalistic; it’s very hard when it really comes down to it that she is no longer around.”

Afraz Khan remembers his grandmother Shamin Humayum

Shamin Humayun was visiting her son’s family in Switzerland when the pandemic hit. As months in lockdown rolled by, the 77-year-old matriarch started feeling restless. She yearned to go home, see her friends and family, run her own home, and make her own schedules, said her grandson Afraz Khan, who lives in Los Angeles and whose mother is Humayun’s eldest daughter.

Against the wishes of her family, Humayun returned back home to Lucknow. At that time, Indians had started letting their guards down and resuming their pre-pandemic lives. For a while, it seemed that she, too, was home free. But then in April, both she and her husband became sick. For the first few days, Humayun breathed through an oxygen tank a relative had procured for her, but soon it became necessary to take her to the hospital. In her last 10 to 12 days, her family felt their hearts rise and fall in conjunction with her oxygen levels.

On a Thursday evening in Los Angeles, Khan’s family were about to break the fast they observed during the holy month of Ramadan, but his mother didn’t want to eat. She told Khan that she had a feeling something was wrong.

“I don’t know what that sixth sense was, but literally two minutes later, my great aunt calls… and she says, you know, Nani Ami is in a better place now,” he said. “I can’t even explain to you the state [my mother] was in, but I’ve never seen her that unstable and fragile — and she’s someone who is so good at remaining so strong for our family.”

Khan announced the death on an extended family group chat, requesting that relatives don’t immediately text or call to give his family some room to process their loss. But almost immediately, his mother regained her composure and told him that it was her job to comfort others who were also grieving for Nani Ami. She could not turn those people away.

Khan remembers his grandmother as someone who resisted the norms of her time. She refused to get married until she finished her education, ultimately earning two Master’s degrees. She played badminton like a pro. And even years later, when she first came to Los Angeles to visit Khan’s family, she made it her mission to learn how to navigate the new, alien city. She familiarized herself with all the bus routes, signed up for aerobics classes at the local senior center, and took computer lessons at the adult school nearby.

“The thing about Nani Ami is that she’s someone who would always tell us, ‘always ask … never accept the status quo. Always try,’” Afraz, who is an MBA student at UC Berkeley Haas School of Business, said. “For someone at her age to always be so fearless inculcated within my sister and me that drive of never taking the status quo as what needs to be accepted.”

It is in that spirit, that when Khan last visited her in Lucknow in December 2019, they attended the mass protests against the citizenship laws that had just been passed in India, which multiple human rights groups said discriminated against Muslims.

“In our faith tradition, there’s this idea that the dead are not truly dead, that their souls are still alive and the ways in which we, who are still living, connect with the souls that have passed away is through doing acts of service in their name,” said Khan, who set up a COVID relief fund in Humayun’s memory. “Through any good we do that was taught to us by those who passed away, it further elevates their souls in the next realm.”

The official Covid death toll in India is upwards of 400,000, but is considered a gross undercount. Even as the number of daily deaths decline, the struggle continues for many serving as frontline workers to combat the pandemic or grappling with indirect fallout of the virus.

Vaidehi Gajjar remembers her mother’s sister, Suchi Shastry

Vaidehi Gajjar hasn’t seen her mother’s sister, her maasi Suchi Shastry, in 10 years. But one of her favorite memories is eating mangoes and hunting for peacock feathers with her aunt behind her mother’s ancestral home in Sidhpur, Gujarat.

When Gajjar visited her mother’s family in India as a child, she often got sick. It was her aunt who would care for her. “She was equal parts strict with me, but also, you know, fun,” Gajjar said.

Shastry lives with osteoporosis, a disease that weakens bone matter. In recent years, she has suffered falls and fractures, and displaced disks in her spine. She is almost entirely bedridden and has needed surgery for a long time, but because of COVID-19, her procedure keeps getting delayed.

As the rock of her family, the one everyone comes to for help and advice, being bedridden and dependent on others has been frustrating.

“She wishes that she could do more because she has been there for everybody so much, and she’s used to being the person that everyone relies on, not the other way around,” Gajjar said. “It has been hard on her mentally.”

Shastry is too rooted in her ways to want to come to America, and even if she did, it would be hard to travel with someone who is in her condition because of pandemic restrictions. So, there’s nothing her family can do but wait and hope for the best.

“I am in health care, I see daily what the pandemic is doing,” Gajjar said. “It feels very helpless, like not being able to do anything and just essentially having to sit back and watch your family members suffer.”

Fatima Husain pays tribute to her sister Dr. Farah Husain

After Dr. Farah Husain returns from the hospital in Delhi, where she works as a critical care specialist, she still finds time to bake a cake with her 5-year-old twins, have a cup of tea with her parents, make dinner with her husband, and finish up writing coronavirus reports for the government.

“Somehow, she also manages to binge watch Netflix shows in the midst of all this,” said her youngest sister, Fatima Husain, who works in venture capital in the San Francisco Bay area. “I genuinely think she has extra hours a day than the rest of us in this world. Doing all those things, I think, is quintessentially Farah.”

Farah, who is eight years older than Fatima, is the oldest of four sisters. Beyond being an accomplished doctor and the most responsible family member, according to Fatima her eldest sister is goofy, loves to sing, and volunteers to help people who are more vulnerable. Behind her no-nonsense exterior, Farah is a softie who loves animals: In her home live cats, turtles, a variety of fish, and maybe soon, a puppy.

The humans in Farah’s household include not only her husband and children, but also her parents and elderly grandparents, so balancing the risks of her work with the safety of her family is an immense challenge during the pandemic — one that she tackles with her signature matter-of-fact resolve.

On her first day in the COVID-19 ICU unit at her hospital last year, Farah had to rush in to help a colleague whose vitals were plummeting and who had to be intubated. The colleague died, and then Husain got sick herself.

For months during the lockdown that followed, she would observe a strict protocol at home, even after she recovered — she wore a mask around her high-risk family members and ate her meals separately. When the government rolled out its halting vaccination drive, she made sure her family was vaccinated.

And yet, they could not escape the second surge. She, her parents, her husband, and even her children contracted the delta variant this year. They were sick for many days and her husband was briefly hospitalized. As her own family battled the virus, and bodies piled up around them, Farah nevertheless found the time to describe the goings-on to the world: “The situation on the ground is nothing short of an apocalypse,” she said on CNN in late April. In very few words, she was able to convey a lot.

Her sisters Fatima and Nazia in the United States watched anxiously from afar. Nazia, also a doctor with two children, kept up with the research on the new variant. Fatima did wellness checks on each member of the family, video chatting with them as they holed themselves up in separate parts of the house.

“Nazia and I feel helpless sitting here, and again, just like, ridiculously grateful for the fact that Farah is there and can make quick side decisions,” she says. Now after the storm, “things are on the mend,” Fatima added, “but everyone’s nervous about the third wave coming about.”

CORRECTION (Aug. 2, 2021, 12:03 p.m. ET): A previous version of this article misstated Dr. Farah Husain’s COVID status after her colleague died from the virus. It’s not clear that she caught the virus, as her COVID test at the time was inconclusive.

Tanvi Misra

Tanvi Misra