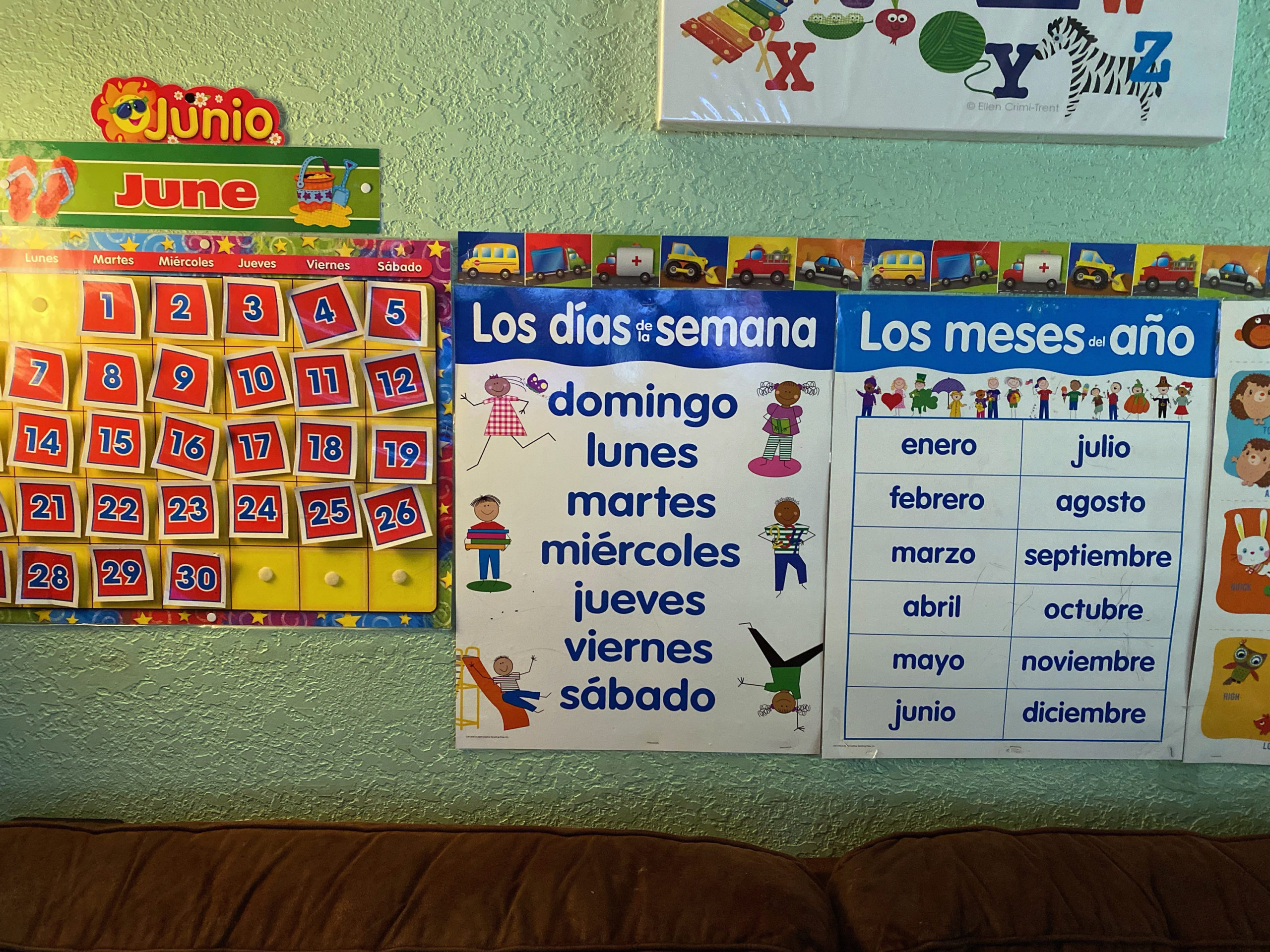

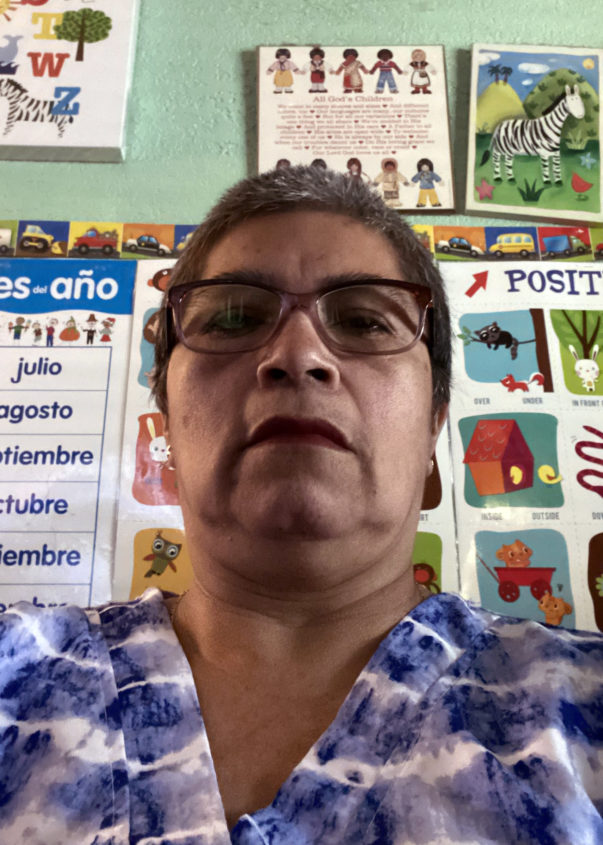

Pictures, toys and learning materials for young children fill Julieta Baxin Pucheta’s basement in Minneapolis, where, for the past 10 years, she has cared for her grandchildren and the children of relatives and friends. Even though she lacks a license to provide child care, Baxin Pucheta, who immigrated to the U.S. from Veracruz, Mexico, in 2001, says she works hard to give the same at-home early learning quality as her licensed peers.

Family, friend and neighbor, or FFN, caregivers like Baxin Pucheta, who are generally exempt from licensing and regulations, provide informal child care primarily to family members and children in their communities. Baxin Pucheta, like many other FFN providers, relies on payments from parents who pay her only when they can afford to, and because of the pandemic they have been unable to pay her on a regular basis.

Related: The Pandemic Devastated Home-Based Child Care: ‘I Don’t Know How We Bounce Back’

However, unlike licensed providers in home-based settings and centers, Baxin Pucheta, 52, and other FFN caregivers have been generally ignored in child care relief efforts, she said. Access to the licensed system, which could help her get access to better pay and resources, is particularly fraught for Spanish-speaking immigrants, she said.

“It’s discrimination,” Baxin Pucheta said. “A lot of times someone in [my] position won’t have all of the requirements … and they’ve created a lot of obstacles in the process.”

Many of the forms she would need to fill out to sign up for a license are in English, a language in which she isn’t comfortable doing important paperwork. She also said buying equipment she would need to meet regulation requirements is far too expensive, which she said is true for many of the Hispanic immigrant women in her community.

Baxin Pucheta, who said she is committed to continuing to provide child care, said that as of June she was over a month behind on her bills, including her mortgage.

Despite the prevalence of FFN caregivers, who are disproportionately women of color, Baxin Pucheta and others say they remain nearly invisible to policymakers, leaving many of them in dire economic straits as more money has moved across the child care infrastructure during the Biden administration.

For Spanish-speaking immigrant communities that use and prefer FFN care and were disproportionately affected by the pandemic, the impact of Covid-19 has been felt even more deeply, and the barriers to support for FFNs are often even greater.

The pandemic “was very hard for FFN child care providers because they lost kids … because families lost jobs, everything was closed and the economy was very low,” said Ruth Evangelista, a co-founder of La Red Latina de Educación Temprana, an organization focused on primarily Spanish-speaking FFN providers. “Because they don’t have a license, it was very hard to get resources.”

FFN caregivers care for about 7 million children under age 6 in the U.S., making it the most common form of nonparental child care, according to a report this year from Home Grown, an organization that supports home-basedchild care providers. Information about the demographics and immigration statuses of FFN caregivers is scant, said Natalie Renew, executive director of Home Grown, because of a lack of investment in research and because most FFN care takes place in private.

A 2015 analysis from the Migration Policy Institute, a nonpartisan think tank, found that about 18 percent of child care workers are immigrants and that immigrants are significantly more likely than native-born providers to be employed in family child care settings like FFN care. The study also found that Spanish speakers in early childhood education were more likely to work in family child care. About 25 percent of family-based providers in the U.S. identify as Latino.

‘Big in the community’

Latino families tend to have higher levels of parental employment and lower levels of income than the average family in the U.S., the National Research Center on Hispanic Children & Families reported in 2019. Latino families are also disproportionately more likely to live in child care “deserts,” according to a 2018 report from the Center for American Progress, a progressive policy institute. Put together, those factors make access to affordable types of child care like FFN crucial.

And experts say that in immigrant communities where Spanish or other non-English languages are predominantly spoken, FFN care is often preferred.

“FFN care is very positive and big in the community, because families have someone who they know will care for their children the same way that they would,” said Wendy Maldonado, 40, an FFN caregiver in Arizona who primarily works with children with disabilities in her neighborhood.

Maldonado said that in addition to caring for many neighborhood children unpaid and developing curated lesson plans for her students — some of whom she helped through pandemic-era online learning — she connects with about 35 families a day about resources and support. “It’s kind of like a family within a family,” she said.

Evangelista said that by tying significant pandemic-related support to licensing, states have shut many Spanish-speaking immigrant providers out of the formal system, leaving them unable to afford even basic necessities. For providers who are undocumented or who live in mixed-status households, immigration status can negatively affect becoming licensed, said Richfield, Minnesota, Mayor Maria Regan Gonzalez, a co-founder of La Red. “People think about their family first and getting separated from their kids,” she said. “And so, obviously, those things take precedence over going through the licensing process to be a licensed child care provider.”

Carolina Hernandez, 38, an FFN provider in Arizona, said that the Spanish-speaking parents she serves trust her because she has training; they take comfort in her ability to give them detailed updates about their children’s progress and to teach their children in a way that honors and fosters their culture and home-language skills.

She doesn’t have a license, so she is ineligible for a lot of pandemic support services for child care providers, including technical and financial support. Hernandez said she has worked with other providers in similar situations to share access to resources — including food — and has continued to stay up to date on early education training.

She said resources should be available to all providers regardless of language barriers or immigration status issues. “They’re all providing the same type of care, and they all care about the kids, and it would be beneficial to them as professionals to grow in their business.”

Related: As Attention Turns to Child Care, the System’s Unsung Heroes Ask for Recognition

Most states allow unlicensed child care providers to participate in federal or state funding programs, but a report in January from Home Grown found that the accessibility and amount of funding unlicensed providers get varies. Most states require household-wide background checks to receive subsidies, which experts say can make it less likely that undocumented providers or providers in mixed-status households will apply for assistance.

“Even in states where FFN providers can access subsidies … it’s unlikely that this is accessible to the majority of FFN providers who may not speak English, who may have less than a high school degree, who may also not be culturally connected and know that these subsidies are available,” said Maki Park, senior policy analyst for early childhood education at the Migration Policy Institute, a nonprofit U.S. and European organization. “Even more so when we’re talking about emergency funding.”

Finding solutions

Some states and nonprofit organizations have turned their attention to finding long-term and immediate solutions. For example, All Our Kin, a nonprofit group advocating for family child care providers in Connecticut and New York, helps Spanish-speaking FFNs navigate the licensing process and helps FFN providers who aren’t looking for licenses to get access to other resources.

Several states, including Nebraska, Louisiana and Oklahoma, also shifted their approaches to pandemic-era FFN care funding, said Renew of Home Grown. Oklahoma created a program for essential workers to use subsidy payments to pay relatives for care.

But for the most part, few states have given significant funding to FFNs or given funding directly to community-based organizations. It has been difficult for groups on the ground like La Red in Minnesota or Home Grown, which partnered with organizations in five communities to provide emergency funding to family child care providers, to get and distribute public funding, Renew said. The organizations have primarily relied on private philanthropy.

Getting funding and help with licensing is crucial for many FFNs. So, of course, is child safety. Addressing both is a balance and a top concern for FFN care support organizations, said Karen Schulman, an expert on family child care at the National Women’s Law Center.

Groups like WHEDco, a New York nonprofit organization focused on family child care providers, tackle the issue head-on by working with both English- and Spanish-speaking unlicensed providers to meet and monitor health and safety standards, help them secure child care subsidy funding and provide support in the licensing process.

Ensuring that FFNs in Latino immigrant communities get support is critical to ensuring that women participate in the workforce after the pandemic, said Patricia Lozano, executive director of Early Edge California, a nonprofit organization focused on early education. “If FFNs are not able to [work], then it’s going to be harder for families to go back to work, especially women,” she said.

Baxin Pucheta, the caregiver in Minneapolis, said recognition of providers like her is the first step toward change. “More than anything,” she said, “I wish that the government would recognize what I’m doing.”

Translations provided by Judith Paredes, supervisor at Candelen. Additional translations provided by Gregory Taylor.

Editor’s note: We did not press sources to disclose immigration status and have not included the immigration status of the women interviewed for this story to protect our sources from deportation or other negative immigration-related impacts.

Jessica Washington

Jessica Washington