Before war forced her to flee Ukraine, Myroslava Marchenko worked as an OB/GYN at a private clinic in Kyiv. Her first question to a new patient was always, “How do you feel about this pregnancy?” While she didn’t perform abortions herself, the procedure is generally legal and accessible in Ukraine, and if a patient wanted to terminate their pregnancy, Marchenko could refer them.

The 32-year-old doctor now volunteers on a helpline offering reproductive health advice to fellow refugees in Poland, which has some of Europe’s most restrictive abortion laws. It allows termination only in cases of rape, incest, or where the mother’s life or health is in danger – something most of the refugees Marchenko counsels were unaware of before they arrived. Her work with the helpline, run by Polish reproductive rights organization The Federation for Women and Family Planning (Federa), has her taking calls from women who have survived rape, left partners behind on the front lines, or who simply cannot fathom giving birth while war rages at home. During her last four-hour shift, three women had called in asking how to get an abortion. “Nobody knew that it’s very difficult here,” Marchenko said. “Nobody knew.”

Related coverage: Poland’s abortion rights protests lead to a louder call for gender equity

More than 5 million Ukrainians have left the country since Russia invaded, according to the United Nations refugee agency, around 90% of them women and children. Of these refugees, nearly 3 million crossed into Poland, although it is not known exactly how many have stayed there. Both Federa and Abortion Without Borders, an umbrella group that helps women from Poland access abortion, have received dozens of phone calls from Ukrainian women asking for information on how to terminate a pregnancy in the country. Abortion Without Borders said that as of April 21, it had received requests for help from at least 158 women.

Marchenko summarized what many of the women who call the helpline tell her: They are strapped for cash in a foreign country, have no means of sustaining themselves, and can’t get support from their families or husbands who had to stay in Ukraine. Many already have children. “It’s always the same story, just the person changes,” Marchenko said. “The reasons are the same.”

Poland provides Ukrainian refugees with state-funded healthcare, and they are eligible to apply for a benefit for every child that amounts to about $120 per month. But even before the war, Poland’s healthcare system was strained and the childcare benefit wasn’t going very far due to rising costs of living. The turmoil around Russia’s invasion of Ukraine has increased these pressures – inflation hit a two-decade high in March, while rents have risen as much as 30% or 40% in large Polish cities in the first six weeks of the war.

I can’t keep this baby, it reminds me all the time of what I’ve been through.

— Ukrainian woman who says she was raped by a Russian soldier

Growing reports of sexual violence by Russian soldiers in Ukraine have added fresh urgency to the situation. There are no exact figures, but rights groups and Ukrainian authorities point to dozens of documented and reported cases in areas from which Russian troops had withdrawn as evidence that the invading forces are using rape as a weapon of war.

In the last week of April, Marchenko got a call from a woman who couldn’t stop crying. The woman came from an occupied region near Kyiv, where she said she had been raped by a Russian soldier. She arrived in Poland with her 14-year-old daughter and some other relatives, but told Marchenko none of them knew she was pregnant. “I can’t keep this baby, it reminds me all the time of what I’ve been through,” Marchenko said the woman told her. “I just want to forget and start my life from the beginning.”

While it’s legal to perform an abortion in cases of rape in Poland up until 12 weeks of pregnancy, doing so is far from straightforward. It requires a prosecutor to certify that the pregnancy was likely the result of a crime – something that rarely happens, according to a 2021 Council of Europe report. In 2018, only one abortion on these grounds was carried out in Poland, and in 2019, there were three.

According to the Polish women’s magazine Wysokie Obcasy, a group of 120 women who reported being raped by Russian soldiers in Bucha, where large numbers of civilians were killed, had planned to travel to Poland until they heard about the restrictions on abortion. The Fuller Project was not able to independently verify the story. The journalist who wrote the story said the women had since received medical care in Ukraine.

“Unfortunately abortion in Poland is a luxury.”

— Urszula Bertin, Activist

Marchenko has received private messages on her social media from other women who say they’d been assaulted by Russian soldiers. One was just 16, another 25, and both were ill-equipped to deal with the bureaucracy around securing a legal abortion in Poland. Federa head Krystyna Kacpura said her organization had received requests for help from several young women in a similar situation. “When we heard, we immediately saw that they had access to emergency contraception, which would still work in their cases,” she said. “They got psychological help. We don’t know any details because they were unable to speak about what happened.”

A group of Polish opposition politicians demanded on March 25 that the government expedite and simplify the legal abortion process for victims of Russian war crimes. When asked about the request, the office of Poland’s prosecutor general and the health ministry both said that the same law that applied to Polish women, applied to refugees. Women’s rights groups have also called on the government to provide sexual and reproductive health care for Ukrainian refugees without success.

In the absence of government help, the onus has fallen on non-governmental organizations. The US-based Center For Reproductive Rights is working with Federa and other local groups in countries bordering Ukraine to put pressure on the European Union to include sexual and reproductive health in their refugee aid solutions. “It’s important to remind these decision-makers that these are some of the most hostile contexts in the European region for reproductive rights,” said Leah Hoctor, the Center’s regional director for Europe, adding that the situation in Poland is the worst.

Poland has had restrictive abortion laws for decades, but a 2020 court ruling that held abortions even in cases of fetal abnormality were unconstitutional led to a dramatic tightening. Reproductive rights groups say the ruling has created an atmosphere where doctors fear prosecution for terminating a pregnancy even when the mother’s life is in danger. At least one pregnant Polish woman has died, reportedly because doctors waited too long to abort the fetus.

“Unfortunately abortion in Poland is a luxury,” said Urszula Bertin of Ciocia Basia, a Berlin-based organization that is part of a network of groups arranging doctors and travel for women in Poland to get abortions abroad. Underground abortions are available in the country, but only to those with the connections and money that most refugees lack, Bertin said, so her organization has helped several Ukrainian refugees who arrived in Poland terminate their pregnancies in the German capital.

Those early enough in their pregnancy can order abortion pills from organizations abroad, such as Women on Web or Women Help Women, to take at home under remote medical supervision. But they must do so alone, because anyone facilitating an abortion could face criminal charges. One doctor from another country in the region suggested to Federa’s Kacpura that they’d send abortion pills to Poland. “I started laughing,” she said. “I could see it: they send us a hundred pills and we immediately get arrested.”

The threat of prosecution is real. Justyna Wydrzyńska of Aborcyjny Dream Team, the leading abortion rights group in Poland, was charged with “helping with an abortion” after she provided medication to a woman suffering domestic violence. The woman’s husband denounced Wydrzyńska, who is a domestic violence survivor herself. She faces three years in prison if found guilty at a trial due to be held in July.

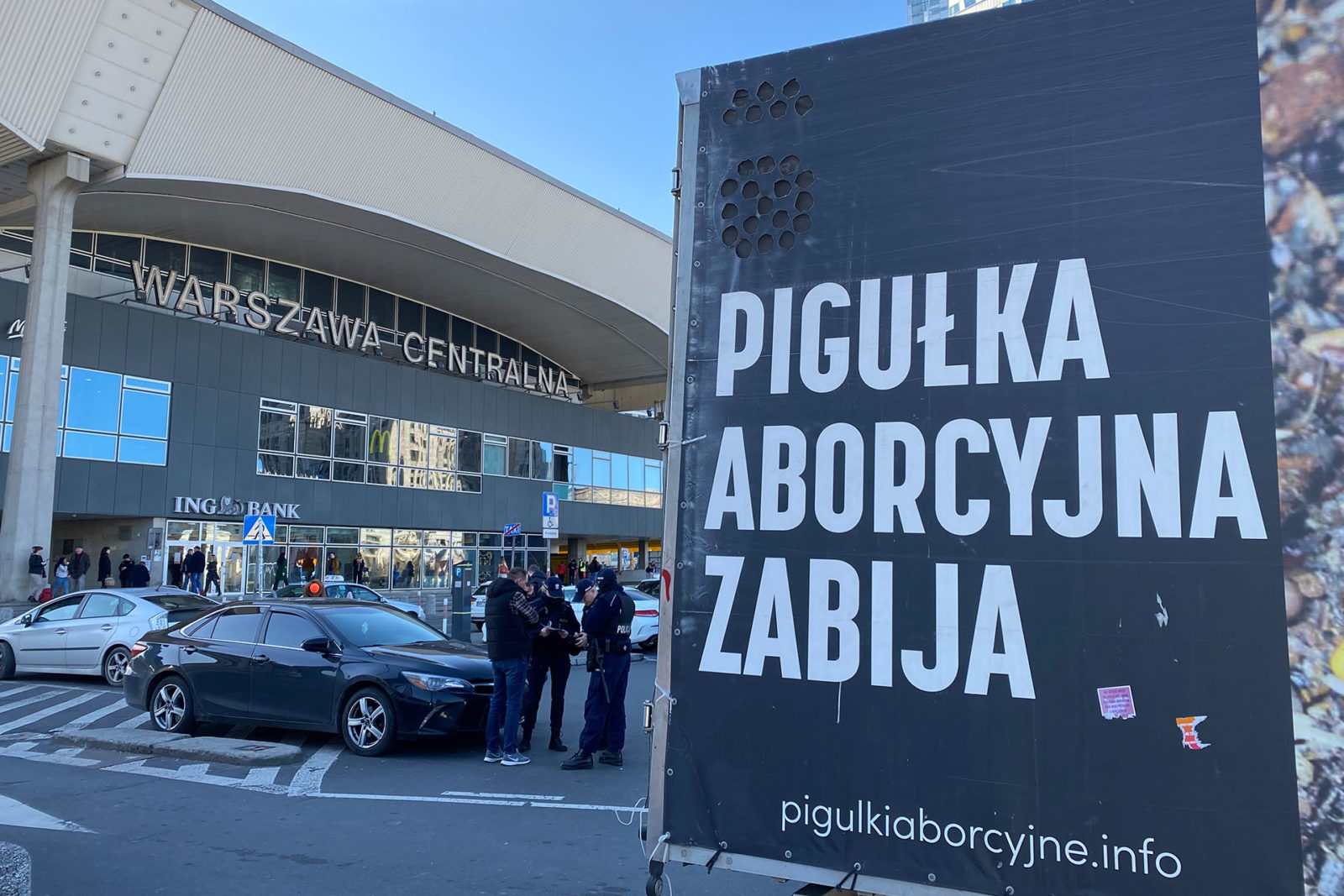

Compounding the challenges they face, Ukrainian women crossing into Poland are being met with anti-abortion campaigners. A truck bearing graphic images of a dead fetus has been parking outside train and bus stations in Warsaw, transit hubs for many refugees arriving in the country.A loudspeaker recording plays anti-abortion slogans on a loop, which a volunteer at Warsaw’s main train station said unsettled the traumatized refugees. A foundation run by the well-known Polish anti-abortion activist Kaja Godek has also been distributing flyers that bear the Mother Theresa quote, “I feel that the greatest destroyer of peace today is abortion.” The flyer, which is printed in Ukrainian and Polish, warns that doctors who provide abortions in Poland may be prosecuted. The foundation did not respond to a request for comment.

None of this has deterred Marchenko, the Ukrainian doctor. Nine weeks into the invasion, refugees are arriving in Poland in smaller numbers, but Marchenko says the hotline is getting an increasing amount of callers asking about abortion. While many of the refugees who came in the earlier days of the war were from safer areas of the country, which generally meant they were more affluent and had connections, Marchenko notes the latest wave of refugees are escaping from combat zones in the eastern regions. Their situation is often more dire, she said: “They have no money and they don’t know how long the conflict will continue.”

Hanna Kozlowska

Hanna Kozlowska