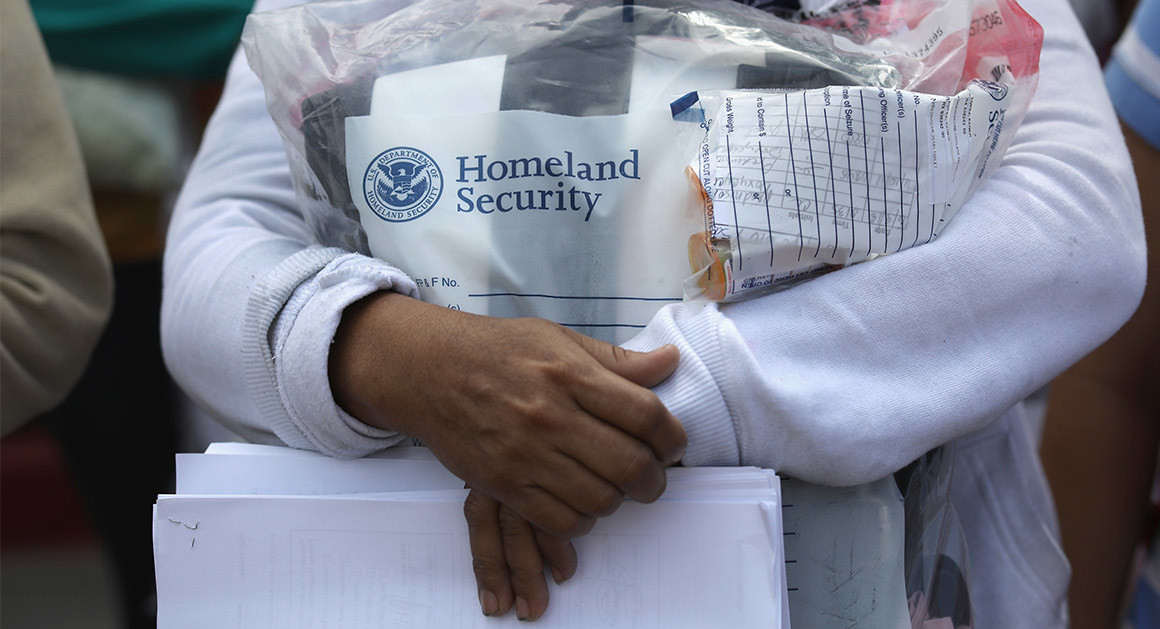

If you’re a migrant seeking asylum in the United States, hope for a female judge.

According to an analysis of data from Syracuse University, which collected outcomes from asylum decisions made by 293 immigration judges from 2015 to 2017, male judges denied asylum in 66 percent of cases. Female judges denied asylum in just 50 percent of cases.

The same data show that migrants are more likely than not to present their cases in front of a male judge. In the sample of 293 judges, which represents approximately 85 percent of all immigration judges, 60 percent were men. And the disparity is getting only worse under President Donald Trump. Trump’s appointments to the judicial bench have been 81 percent male, according to an analysis by The Associated Press last year.

Gender imbalances in the justice system have been well documented, from law enforcement up to the highest levels of the judiciary. But less explored is what effect that is having on how justice is dispensed in the United States.

It’s hard to know how much of the disparity between denial rates from male and female judges is due to gender and how much is a product of other factors. For example, one of the variables most highly correlated with asylum denial is if a judge has a prosecutorial or other enforcement background—and that is a group that tends to skew male. The volume and kinds of cases assigned to a particular judge matter, too. But differences by gender exist even within the same court, where cases are randomly assigned and less subject to caseload variations. Male judges in Chicago, for example, denied asylum 60 percent of the time. Female judges did just 40 percent of the time. In San Antonio, the difference was even starker. Male judges there denied asylum 80 percent of the time and female judges did 35 percent of the time. These findings, while not uniform across all immigration courts, are consistent with a 2007 study, one of the few to look at the gender disparity in immigration courts, which found that “an asylum applicant assigned by chance to a female judge … had a 44 percent better chance of prevailing than an applicant assigned to a male judge.”

While it’s tough to untangle gender from all of the other variables that come into play, the marked disparity in asylum outcomes for male and female judges suggests that gender matters in asylum decisions, even if it works in tandem with other variables.

This gender disparity could be reinforcing a six-year trend toward permitting fewer refugees and migrants into the United States and new efforts by the Trump administration to further curtail the granting of asylum. In 2012, less than half of asylum applications were denied. By 2017, that number was 62 percent. On Monday, Attorney General Jeff Sessions issued guidance directing that domestic violence, along with gang violence, should generally not be considered grounds for asylum, reversing 2014 precedent set by the Board of Immigration Appeals that gave asylum to a Salvadoran woman on that basis.

The idea that women might judge differently than men is an uncomfortable proposition for those who believe that a judge’s job is an inherently impersonal one. But the proposition has at least one prominent defender. In a 2009 interview with USA Today, Supreme Court Justice Ruth Bader Ginsburg commented on a decision by her eight male colleagues, who in a ruling said they were untroubled by the strip search of a 13-year-old girl by school officials who accused her of hiding ibuprofen pills. Ginsburg deadpanned, “They have never been a 13-year-old girl.” According to president of the American Bar Association, Hilarie Bass, it’s impossible to consider every legal matter in a vacuum. “Everybody brings their life experiences to every decision they make.”

Read article here.

Rikha Sharma Rani

Rikha Sharma Rani