VYONGWANI, KENYA – Mwaka Chimera sits on a worn-out leather couch outside her two-roomed house in Vyongwani village, in southeastern Kenya, cradling her newborn daughter.

“I dropped out of primary school, and for my first five pregnancies, I never attended a single antenatal clinic. I would just show up at the hospital when it was time to give birth,” Chimera, 31, says in Swahili. “The difference in how I’ve cared for my last two children is remarkable, all thanks to what I learned in the group.”

Through her local mother-to-mother support group, Chimera says she’s learned the importance of prenatal checkups and key screenings, including HIV testing. The group was part of Stawisha Pwani, a $47-million project that began in 2021 and was due to be completed in June 2026, but came to an abrupt end when, after the aid freeze in January, the U.S. State Department announced in March that it would be stopping all but a small percentage of projects funded by the U.S. Agency for International Development (USAID).

According to data provided to the International Aid Transparency Initiative (IATI), Stawisha Pwani was delivered by LVCT Health, a Kenyan nonprofit that implements health programs, in partnership with local governments. Its mobile clinics, doorstep care for mothers in remote areas, and life-saving medicines have transformed access to health services in the coastal counties of Kwale, Mombasa, Kilifi and Taita Taveta in southeast Kenya.

“The program has truly transformed lives in this village,” she says as she gently rocks her baby. “I only wish it could continue – for the mothers who still need this support, for the babies yet to be born.”

$9.2 million of the original project budget is left unspent.

Painting a picture of dependency

To get a sense of the global impact of the aid freeze, The Fuller Project analyzed data submitted by donor countries to the Organisation for Economic Cooperation and Development (OECD) and focused on four key sectors that disproportionately affect women: reproductive health, including pre- and postnatal care, delivery, infertility treatment and post-abortion care; family planning, including the provision of contraceptives, counseling and education; ending violence against women and girls; and supporting women’s rights organizations, movements and institutions. Reporters then combed through IATI data to identify specific programs, like Stawisha Pwani.

The data revealed that, while the U.S. has long been the largest donor of foreign assistance – contributing just over one-fifth of the world’s aid in 2023 – its commitment varies by sector and region.

The U.S. contributed more than half – 54% – of the foreign assistance provided by all countries for family planning and 45% of the total for reproductive health care in 2023, the last year for which figures are available, according to a Fuller Project analysis. In the same year, 26 countries received more than half of their family-planning aid from the U.S. – 19 of them are in Africa.

Kenya itself received approximately 27% of all its aid from the U.S., including more than 60% of its family planning and reproductive health care funding. Since the aid freeze, local health officials have been scrambling to continue to offer what services they can.

“As part of our immediate plans, we have requested approvals [from the local assembly] to absorb half of [approximately] 122 members of staff from the Stawisha Pwani project onto our payroll to ensure project continuity,” says Peter Mwarogo, health executive in Kilifi, one of the counties where Stawisha Pwani was implemented.

Against the backdrop of calls for Africa to seize this opportunity to rethink its reliance on aid, the Government of Kenya says it needs $522.16 million to sustain primary healthcare, procure essential medicines, and cover the funding gap left by USAID’s withdrawal. The Treasury is set to present its 2026 budget in April.

“We are reviewing current budget allocations to ensure that essential services in health, education, governance, and food security remain a priority,” Treasury Minister, John Mbadi, told parliament in March.

In the meantime, global health experts warn about the damage the stop-work order will cause, both to individuals and to health systems.

“Unfortunately, the fallout from these funding cuts will hit women the hardest, as they make up the majority of primary healthcare consumers, not just in Kenya, but across Africa,” says Dr. Stellah Bosire, executive director of the Africa Center for Health Systems and Gender Justice.

“Funding cuts don’t just disrupt reproductive health; they unravel entire healthcare systems,” Bosire adds. “These policy shifts widen funding gaps, putting millions at risk of losing access to essential healthcare services and jeopardizing vital work that has taken years to build.”

Her words are echoed by Evelyne Opondo, Africa Director at the International Centre for Research on Women.

“The progress we’ve fought so hard for is now at risk,” Opondo says. “Urgent action is needed to safeguard the lives of women and children, who will be the hardest hit by the ripple effects of USAID funding cuts.”

Back in Vyongwani, Musa Omar Mlamba, one of only two male ‘community health promoters’ at Vyongwani Health Centre, is deep in preparation for the next bi-monthly training with his group of 15 women.

“This session will focus on child nutrition, best breastfeeding practices, and maternal health. I’ll emphasize the importance of eating five balanced meals a day to ensure enough milk production,” he explains.

In a field dominated by women, he stands out – not just for his gender but for the trust and connection he has built with the mothers he serves.

“Empathy is everything in this job. My support group is thriving [because] I listen and I show up for them when they need me,” he says with pride.

But uncertain times lie ahead. For now, Mlamba has been able to continue working because he was on Kwale County’s payroll before the Stawisha Pwani program began. He hopes the county will still provide monthly stipends as before, but with Kenya’s health care system likely to be hardest hit by USAID cuts, as reported in February, it’s impossible to say how secure his employment is.

“No one has told us whether we’ll be retained or if we’ll even be paid,” he says. “With my children in school, I genuinely don’t know what to do. Who will support those who have dedicated themselves to supporting others?”

Methodology:

Data analysis for this story relied on two primary sources of information on U.S. and international aid spending: the The Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development’s Creditor Reporting System database and data published by donors to the International Aid Transparency Initiative (IATI).

OECD data (accessible via the OECD’s Data Explorer) was used to put in context the U.S. contribution to total aid and for sectors that disproportionately affect women and girls. This data was extracted in constant (inflation-adjusted) prices to be able to look at aid over time.

IATI project-level data (accessible via the d-portal.org website) was used to identify specific projects, within these sectors, likely to be affected by the U.S. aid freeze.

Credits:

Data journalist: Claire Provost

Reporters: Allan Olingo and Jodi Enda

Data visualization: Claire Provost and Erica Hensley

Editors: Eliza Anyangwe and Maher Sattar

Additional data researchers: Allan Olingo, Louise Donovan and Erica Hensley

Photographer: Kevin Odit

Editor’s note: the story was edited to clarify that 83% of USAID projects were cancelled in March.

In April last year, classrooms at the Asa Primary School in eastern Kenya fell silent as the worst drought to hit the region in four decades forced children to stay home. When the October rains came, the lively chatter of children was restored, but with a marked difference – this time, there were hardly any girls.

When the drought was at its worst, “everyone was in survival mode,” said Roba Racha, a local government official. “The devastation caused by the drought in the area forced many children to leave school.”

After the worst was over, the boys began to return. But many of the girls never came back, said Racha, whose district southeast of Nairobi, near the Somali border, is home to pastoralist communities that depend on grazing for their livelihoods.

“You could walk into the classroom and find only boys,” Racha said. As the drought took its toll, school numbers more than halved. One head teacher in the area said his school had classes without a single girl.

It is a story repeated in many parts of Kenya, with girls much more likely than boys to have to drop out of school to help struggling parents when natural disasters like droughts or floods hit. And the changing climate is making those a more frequent occurrence.

In recent years, Kenya has been hit first by severe drought that left millions hungry and destroyed the livelihoods of pastoralist communities, then by large-scale flooding that displaced many thousands and washed crops away.

Experts in the region say girls’ education is often the first thing families sacrifice when faced with the effects of climate change. In a drought, some girls take on the back-breaking task of fetching water over ever-longer distances, while others take care of things at home as their parents seek grazing for their herds. Some are married off as children to bring income in the form of a dowry and reduce the number of mouths the family has to feed.

Their marriage potential makes girls a sort of “life insurance” for pastoralist families that have lost their livestock to drought or floods, said Jedidah Lemaron, who runs a foundation that supports girls in southern Kenya’s arid Kajiado region, home to the Maasai pastoralist community.

“The education of sons is given priority over that of daughters,” she added, with girls more likely to take on the burden of household work during periods of additional stress following a drought or a flood.

Kajiado resident Susan Nakimoru was married in 2022 aged 16 after her father lost his animals to drought. Her parents told her that if she got married, she would save her family and allow her brothers the opportunity to do the same – without animals to give away as dowry to a bride’s family they would be unable to wed.

“I was not ready to get married, but my father insisted,” said Nakimoru, fiddling nervously with the traditional Maasai yellow shawl she wore draped over her shoulder.

Research published last year by the Education Development Trust in six pastoralist regions in Kenya prone to both drought and flooding found that climate shocks typically result in increased responsibilities for girls compared to boys, leaving most out of class. The research, based on interviews with local school principals and community members, found that with each cycle of climate shocks girls were more likely to miss school and lose learning time.

It’s not just a Kenya problem. Climate-related events prevented at least four million girls in low- and lower-middle-income countries from completing their education in 2021, according to a report from the Malala Fund, an education advocacy group. If current trends continue, by 2025 climate change will contribute to at least 12.5 million girls being prevented from completing their education each year, it said.

In 2022, 15 million children in the Horn of Africa were out of school because of the drought and another 3.3 million children were at risk of dropping out, according to UNICEF estimates.

Angela Nguku, executive director of White Ribbon Alliance Kenya, a local NGO that advocates for girls’ rights warned that the substitution of unpaid care work for education is hurting the future of these girls.

“In both extremes of climate change, girls are pulled out of school to take on the role of caregivers at home. It is a never-ending cycle at the expense of their education,” she said.

Research published in 2020 by another non-profit, the International Center for Research on Women (ICRW), found that giving families cash or other support in the form of uniforms or school supplies as long as their girls attended school boosted educational outcomes.

Meanwhile, Kenya’s education ministry is building more boarding facilities in drought-prone areas to allow children to stay in school when their parents have to move to feed their livestock.

The culture around girls’ education, however, may be harder to build.

Last year Mary Enkaroi, 16, had to drop out of her school in Kajiado to help look after her younger siblings when her father left the family to seek grazing for their animals further afield. She never went back.

“There was no rain in our community. We had to walk more than five hours every day to fetch water while my father went to Tanzania to find pasture for the animals,” she said as she walked home carrying a 20-litre bucket filled with water, taking its heavy weight on her head.

“In school, I loved science and wanted to be a nurse, but I now don’t know what my future will be.”

A contractor at the centre of a BBC investigative report exposing the sexual exploitation of women working on tea plantations in Kericho, Kenya, has been allowed to contest in an election for a key tea agency, causing an uproar among Kenyan women leaders, rights activists, and international tea lobby groups.

John Chebochok, who was sacked by James Finlays Kenya (now Browns) in February 2023, is contesting for election on June 28, as a regional director of the Kenya Tea Development Agency (KTDA). KTDA is a private entity with over 600 smallholder farms in 16 tea-growing counties in Kenya.

Chebochok and other managers were filmed by the BBC’s Africa Eye and Panorama programmes in February last year, exploiting female workers in exchange for contract extensions and better working conditions. The programme included detailed testimonies of sexual exploitation by workers, as well as undercover footage implicating Chebochok as a key perpetrator.

After the programme aired, Finlays said it had fired Chebochok and others and banned them from its tea estates. It also reported the suspects to the police for investigation, but so far, no prosecutions have taken place.

Now pressure groups, led by Kenya women parliamentarians, have come out to protest against Chebochok’s candidacy, saying that allowing him to contest in the KTDA director elections is an injustice to his victims.

“We are expressing grave concerns about Chebochok’s candidacy,” said Leah Sankaire, chair of the Kenya Women Parliamentarians Association.

Given the nature of the allegations against him, she said it was imperative that his suitability be scrutinised.

“Electing him to this position will pose a risk to his juniors, especially women workers, who may be vulnerable to further exploitation under his leadership,” she said.

The Coalition Against Sexual Violence (CASV), a lobby group of 13 human rights organisations in Kenya jointly said Chebochok’s candidacy was “a grave injustice to the courageous survivors of sexual violence who have come forward to hold him to account.”

The potential election of this individual, the group said, poses a reputational risk to Kenya’s tea sector.

“We have already seen managers dismissed for similar offences rehired by other tea companies, perpetuating a culture of impunity and discouraging victims from speaking out about their abuses,” they said.

UK-based Ethical Trading Initiative (ETI), a leading alliance of trade unions, NGOs and companies working together to promote human rights in global supply chains, also condemned his candidacy and called for Chebochok’s removal from the election process.

“His candidacy undermines the work of concerned stakeholders across the Kenyan tea industry to address the endemic sexual exploitation and gender-based violence that too many workers face,” ETI said in a statement.

Ethical Tea Partnership (ETP), another UK-headquartered tea lobby group said it had written to Kenya’s electoral body, the KTDA, and the Tea Board of Kenya to express its concerns about Chebochok’s candidacy.

“We call for swift and clear action to ensure that apparent perpetrators of sexual exploitation, abuse and harassment are not employed in positions where they can continue to facilitate physical and economic exploitation and abuse,” the lobby group said.

Kenya’s electoral body, the Independent Electoral and Boundaries Commission (IEBC), is expected to hold elections for directors of the 54 smallholder tea estates managed by the KTDA.

According to KTDA, eligible candidates for the directorship must, among other requirements, have an Ethics and Anti-Corruption Commission (EACC) clearance and a valid police clearance certificate.

The police clearance certificate is issued by the Directorate of Criminal Investigation (DCI) to those who have no pending criminal investigations or convictions. The EACC certificate is also issued to those who do not have any questionable ethical and/or corruption background.

Women in East African countries are facing new tax measures that will affect their daily lives as their parliaments debate and approve budgets for 2024.

From new taxes on sanitary pads, diapers, second-hand clothes and fuel, finance ministries in Kenya, Uganda and Tanzania have proposed new tax measures that will affect the basic cost of goods and services, some of which will hit women hard.

In Kenya, women received temporary reprieve in the amended Finance Bill after parliament removed proposed additional taxes on locally manufactured sanitary pads and diapers. However, for the kenyan women, they will still have to bear with higher costs for imported sanitary pads and diapers, that is majority used by the women given production constraints of the locally manufactured one

This comes even as Tanzania increased taxes on diapers and on second-hand clothes (mitumba), a trade dominated by women.

The changes to Kenya’s Finance Bill came after weeks of pressure from activists and citizens on online platforms calling out the government’s proposals for these taxes, which they argued would push more girls and women out of the affordability of sanitary pads.

“The bill proposes a new eco-tax on sanitary pads, making them even more expensive for millions of women and girls. This move is particularly insensitive given that many already struggle to access affordable menstrual hygiene products,” reads part of a petition against the bill on change.org.

On Tuesday, in a partial victory for women, the Finance Committee of Kenya’s National Assembly bowed to pressure from various stakeholders and dropped a number of controversial clauses in the Finance Bill 2024, including the eco-tax on sanitary pads and nappies.

Kimani Kuria, the committee chairperson, said locally manufactured products will not be subject to the eco-tax as it will only apply to imported finished products.

“Consequently, locally manufactured products including sanitary towels, diapers and others that we had highlighted will not attract the eco-tax. The eco levy will only be chargeable to imported finished products,” Kimani said.

The controversial proposal had sparked an outcry, particularly from women’s groups and activists, who called on the state to address period poverty.

But nominated Senator Gloria Orwoba and period shaming campaigner pushed back against the pressure, pointing out that Parliament was not trying to impose any form of tax on sanitary towels.

“In fact, even the eco-tax that will be imposed on manufacturers will not affect local manufacturers of sanitary towels and nappies,” says Ms Orwoba.

On the contrary, Ms Orwoba says, the Finance Bill proposes to remove a policy that prevents manufacturers of zero-rated products, including sanitary towels, from charging VAT.

Kigumo legislator Joseph Munyoro had condemned the move to charge a levy on diapers saying it would burden women and mostly young mothers.

“What do young mothers do now that you want to impose a levy on diapers? Are you asking them to go back to using napkins?” Munyoro posed.

Tanzania has also proposed to increase the duty on baby diapers from the current 25 percent to 35 percent to encourage local production of the products. It has also reduced the 25 percent tax on raw materials used in the local production of these diapers.

It has also proposed to zero-rate fabrics and garments made from locally grown cotton. It has also reduced taxes on vitenge from 50 percent to 15 percent.

On second-hand clothes, Tanzania is now proposing a 35 percent tax on second-hand clothes, shoes and items. It previously charged 35 percent or $0.4 per kilo, whichever was higher. But it has siince done away with the per kilogramme limit, meaning traders will pay more depending on the volumes they bring in.

It now joins Uganda, which in January increased rates by 3 US cents per kilo from $1.16 to $1.19.

But the commissioner of customs at the Uganda Revenue Authority says they had considered changing the rates earlier in the year, but shelved the idea. We usually review the rates at the beginning of the year but we have shelved the proposal.

However, the Uganda Dealers in Used Clothing and Shoes Association says the new tax change is in place and has already forced some traders out of business.

“We are seeing most of our members dropping out,” said Lydia Ndagire, the association’s vice chairperson.

Kenya has also proposed to further increase the road maintenance levy on petroleum products from Sh18 ($0.14) to Sh25 ($0.19).

“This is expected to further increase the cost of doing business and particularly hurt informal businesses – the majority of which are run by women,” Thomas Kinyonda, an economist at Atlas said.

It has also proposed a 3 per cent export and investment promotion levy on liquid fuel (kerosene) stoves, which is expected to hit women in informal settlements and the low-income group hard.

In 2023, Kenya increased VAT on petroleum from 8 per cent to 16 per cent, which the Kenya Gender Budget Network (KGBN), the National Taxpayers Association and the Collaborative Centre for Gender and Development (CCGD) jointly said “has the greatest negative impact on marginal small and micro enterprises (SMEs) – mostly informal businesses where women are in the majority”.

The 2024 Finance Bill also proposed to increase the excise duty on mobile money transfers to 20 percent. In 2023, this had been increased to 15 percent from 12 percent. At the time, women’s groups said this was likely to create a barrier to accessing financial services, particularly for women SMEs that rely heavily on mobile money services.

However, treasury CS Njuguna Ndung’u dropped the proposed increase and maintained the current 15 percent.

In Uganda, the Ministry of Finance had also proposed in April, through the Excise Duty Amendment Bill, 2024, to increase taxes on its petroleum products to Ush1,550 ($0.42) per litre of petrol and diesel, and a further Ush550 ($0.15) per litre of kerosene, a product largely used by women in the poor and low-income bracket, from Ush200 ($0.05). However, this proposal was dropped by parliament after public outcry.

However, after weeks of protests, Kenya’s President William Ruto said on Wednesday that he would not assent to the new tax proposal and sent the Finance Bill back to parliament. However, the tax proposals remain active (not yet law) as they have already been passed by parliament. It is now expected that in the coming weeks an amendment will be presented to lawmakers to delete the entire tax bill. It will then become null and void.

It was just before Christmas. A family tradition, the first for 8-year-old Gloria Moraa. She sat holding a broken mirror in her hands, watching her aunt paint her coily hair with chemicals that would straighten every strand.

“All the young girls would get matching hairstyles for the holidays, and relaxers were fashionable back then,’’ said Moraa, who lived in Mombasa, Kenya at the time.

With each application of the relaxer, the chemicals began to irritate her scalp, and Moraa started to cry. But she said it was worth the pain when she had straight, shoulder-length hair for the first time, like the little girls on the Venus relaxer box.

“Everyone was admiring our hair, and that encouraged us to keep it relaxed,” she said.

Today, Moraa, 28, lives in Nairobi and alternates between faux locs and natural hair styles. Over the years, she said she used almost every relaxer on the market, from TCB Naturals to Dark & Lovely.

When she relaxed her hair, she had one goal: The product had to make her coily hair silky. The ingredients didn’t matter.

“I did not have the time or the expertise to discern the effects of listed ingredients,” Moraa said. “I am a consumer, not a chemist.”

She said she quit straightening her hair only recently because it seemed relaxers caused it to thin.

Growing evidence suggests the products might have far more serious consequences.

In October 2022, the U.S. National Institutes of Health found women who used hair relaxers more than four times a year were at higher risk of developing uterine cancer.

The study became a tipping point in the conversation in the United States, building on more than a decade of scientific research linking chemicals known as endocrine disruptors in hair relaxers to uterine and breast tumors. Endocrine disruptors are chemicals that interfere with hormones that regulate a range of functions such as mood, appetite, cognitive development, puberty and reproductive health.

While many Black women in the United States are rejecting chemical straighteners — and filing thousands of lawsuits against manufacturers in the wake of the study — sales of the products in some African countries continue to climb.

Tunisia, Kenya and Cameroon were among the top five countries in sales growth for perms and relaxers from 2017 to 2022, according to Euromonitor, a global market research firm. Sales in Tunisia and Kenya jumped as much as 10% over the five-year span. South Africa and Nigeria also saw growth.

“People still use hair relaxers as much as they did in the past,” said Joseph Kiemo, who runs Kiemo Hair and Beauty Studio in Nairobi.

Africa is a lucrative business market for many industries, including cosmetics. It has the youngest and fastest growing population of any continent, with an expanding middle class and a flourishing community of millionaires. With an eye on the future, companies are developing more hair and skin products to meet the needs of the continent’s primarily Black consumers.

The global hair relaxer market is expected to grow from $718 million in 2021 to $854 million annually by 2028.

The companies at the center of the U.S. lawsuits produce some of Africa’s most popular relaxers. Dark & Lovely, owned by L’Oreal, is the top relaxer in Nigeria. ORS Olive Oil No-Lye Relaxer, produced by Namaste Laboratories LLC, is in second place. In Kenya, TCB Naturals is a popular relaxer owned by Godrej Consumer Products Ltd., which describes itself as the “largest player globally in hair care for women of African descent.”

For many Black women, chemically straightening their hair is a rite of passage informed by unspoken Eurocentric definitions of beauty that favor long, straight hair and are rooted in colonialism and racism. But women also say manageability, flexibility and social acceptance drive the decision to straighten their hair.

It’s a shared experience throughout the African diaspora.

“We understand that Black women use hair relaxers for a range of reasons, some within their control, some not,” said Seyi Falodun-Liburd, co-director of Level Up, a gender justice organization in London. “And so, for us, it’s not about shaming any Black woman about making whatever choices she makes.”

Instead, it’s about government and corporate accountability, said Falodun-Liburd, who led a campaign to get L’Oreal, one of the world’s largest beauty and cosmetics companies, to remove its hair-straightening products from the market following research in 2021 linking relaxers to an increased risk of breast cancer.

Governments should do a better job of banning dangerous ingredients, she said, and they should require companies to disclose their products’ potential health effects.

In May 2022, before the National Institutes of Health study, Level Up released the findings of what it says is the first research about Black women’s experience with relaxers in the United Kingdom, surveying more than 1,000 women. The research was done in conjunction with Treasure Tress, a subscription service offering products for naturally curly and kinky hair.

Falodun-Liburd wasn’t surprised by results of one survey question asking whether respondents were aware that long-term use of some relaxers was tied to a 33% increase in breast cancer: 77% said, “No.”

“I think most Black women would not consciously decide to put something on their head that would harm them, and the issue is that most Black women don’t know [what’s in the products],” she told The Examination in an interview.

Ikamara Larasi, a campaigner with Level Up, said the study confirmed why the producers of hair care relaxers should be transparent about their ingredients.

“The price of Black women’s beauty should never be Black women’s health,” Larasi said.

‘Now it makes sense’

Mary Cunningham of New York City is among thousands of people suing the hair-care companies. Her daughter, Telichia Cunningham-Morris, died of uterine cancer more than two years ago after years of using relaxers.

When Cunningham-Morris was a little girl, she wore her relaxed hair in three pigtails that skipped past her shoulders. That was her favorite hairstyle.

Her mother started chemically straightening Cunningham-Morris and her sister’s hair when they were 6 or 7. Relaxing her daughters’ locs made managing their hair and a busy family life easier for her, Cunningham said. She typically straightened her daughters’ hair every six to eight weeks.

Kiddie Kit was the name of their first relaxer. The brand is long gone. But in an old photo from the 1980s, the relaxer box is decorated with drawings of an adolescent Black girl, her thick straight tresses sweeping her shoulders as she swims, bikes, and cartwheels with a young male admirer. Also on the box, the words Mild. Gentle. Safe.

Cunningham-Morris used relaxers for decades, then about six years ago, she and her sister made a pact to go natural, influenced by growing discussions about the harms of relaxers. But her time styling her natural hair was short-lived. On June 15, 2021, she died of uterine cancer at age 50. She spent her last days in her mother’s home in Jamaica, Queens in New York City.

Cunningham, 75, and her younger daughter, Travias Cunningham-Case, 52, believe chemicals in the relaxers caused Cunningham-Morris’s death — and their hysterectomies. Cunningham had surgery to remove fibroids nearly a decade ago; Cunningham-Case’s surgery was for endometriosis.

“It just seemed like all three of us had some kind of female problems all the time. Now, it makes sense to me that's where it came from,” said Cunningham, reflecting on the price she believes her family paid for straight hair.

Regulations lagging around the world

Some of the most concerning ingredients in hair relaxers, scientists say, are formaldehyde, a known carcinogen, and phthalates, parabens and Bisphenol A — chemicals known or suspected to be endocrine disruptors.

Bisphenol A, which appears under various names on relaxer boxes, is used to produce plastics. Phthalates make plastics more durable and parabens help preserve ingredients in cosmetics.

The Examination found that products sold in some African countries contained parabens and fragrances. Phthalates are often found in fragrances and aren’t included in the list of ingredients other than as “fragrances.”

Scientists say the cumulative effect of a combination of chemicals in hair care products, from relaxers to hair dyes, is especially concerning.

Despite more than a decade of research about the adverse health effects of chemicals in relaxers, regulation varies across Africa and the globe.

The European Union bans some endocrine disruptors in cosmetics and has proposed prohibiting the chemicals in other products, including toys. The EU says it hopes to “phase out the most harmful chemicals in consumer products” by 2030.

The United States does little to regulate cosmetics as a whole, including hair relaxers. While Brazil, Canada and other countries banned or restricted formaldehyde in relaxers years ago, the U.S. Food and Drug Administration only proposed to ban the carcinogen last fall. The agency could make a decision this month.

Some African countries, such as Nigeria, have warned consumers to avoid using hair products that contain formaldehyde.

Most countries worldwide require companies to list ingredients on product boxes. Health experts, however, say listing ingredients doesn’t mean consumers understand the potential harm of relaxers.

“The more we educate [people] about what these chemicals are and the potential adverse health effects that may be associated with them, perhaps people could make more informed decisions about whether to use these products,” said Adana Llanos, an epidemiologist and professor at Columbia University’s Mailman School of Public Health and co-author of a 2022 article suggesting policy changes to reduce exposure to potentially harmful hair products.

Llanos is working with investigators at the state-sponsored Kenya Medical Research Institute to study hair and personal care product use in Kenya.

Women in the U.S. began to sue relaxer manufacturers by the hundreds shortly after the publication of the 2022 NIH study. The lawsuits claim the companies failed to warn consumers that relaxers could increase risks of uterine and breast cancer, fibroids and endometriosis.

The companies denied wrongdoing and claimed the plaintiffs’ injuries were not caused by their products.

In November 2023, a federal judge in Chicago ruled that thousands of claims against a number of companies, including L’Oreal, Revlon, Namaste and Godrej could proceed, opening the door for a massive court battle that industry observers are comparing to the Johnson & Johnson talc-based baby powder lawsuits. More than 50,000 plaintiffs accused Johnson & Johnson of failing to inform consumers that the powder, which was heavily marketed to Black women, had been linked to risks of ovarian cancer. The company replaced the product but hasn’t settled with the plaintiffs.

Godrej, Revlon and Namaste did not respond to The Examination’s request for comments.

A L’Oreal spokesperson criticized the NIH study in an email saying it was based on “a small number of uterine cancer cases” and “does not conclude that using these products causes certain health outcomes, such as uterine cancer. Tellingly, the study states that ‘more research is warranted.’”

Additionally, the spokesperson said: “Our hair relaxer products do not contain any ingredient defined as an 'endocrine disruptor' by the World Health Organization.”

The WHO considers parabens to be “potential” endocrine disruptors. It is expected to update its definitions next year based on research from the past decade.

International advisory and regulatory bodies have long wrestled with product testing and identifying endocrine disruptors and other potentially harmful chemicals, according to scientists who study the hormone system. They note that parabens — contained in most hair relaxers — are widely considered endocrine disruptors.

Previously, Revlon told Reuters the company did not “believe the science supports a link between chemical hair straighteners or relaxers and cancer.”

Kate Akpabio, a seamstress in Lagos, Nigeria, was washing her braided hair in a salon on a hot Saturday afternoon in December. Akpabio, who has been straightening her hair with Mega Growth relaxers for seven years, had read on Facebook about the study linking frequent use of straighteners with cancer.

“It doesn’t change my attitude towards relaxing my hair,” she said. She didn’t know about the U.S. lawsuits against hair-care manufacturers.

Favour Godwin didn’t know about the lawsuits or the NIH study. Godwin, a former trader at Computer Village in Lagos, had experienced a burning and itchy scalp from some relaxers. But she said she hadn’t heard anyone talk about the health risks in Nigeria and that she didn’t plan to quit relaxing her hair.

“I can’t even cope without relaxing my hair every two months,” she said.

Opting for natural look

Even before the lawsuits against hair care manufacturers, sales of relaxers in the U.S., the most lucrative product market, were declining as a natural hair movement began to flourish nearly a decade ago.

In the United States, relaxer and perm sales declined by about 9% between 2017 and 2022.

Sales of relaxers will probably continue to dip, according to Caro Bush, a research analyst for market research firm Euromonitor. “Consumers are apprehensive of the chemical composition of these products and their impact on health,” Bush said, adding that the lawsuits intensify mistrust of relaxers in the United States.

She says the U.S. demand for natural hair care products that don't chemically alter hair texture is presenting a market opportunity.

Large companies have acquired some of the small natural hair care brands in recent years. Last year, Procter & Gamble bought Mielle Organics, a Black-owned natural hair care company. And some global companies have created products. More than two years ago, L’Oreal launched Dark & Lovely Blowout, a hair cream that says it protects natural hair from straightening with a flat iron or other heated styling tool.

In Africa, interest in natural hair products is growing alongside the sales of relaxers.

Leshme de Bruyn, who lives in Cape Town, South Africa, sells her line of natural hair care products called Miss L - Embrace My Roots.

A bad experience with hair dyes and relaxers inspired her company motto: “My products will bring you back to the natural hair you had before it started to get chemically damaged.”

De Bruyn said in an interview with The Examination, “Nowadays, they don’t do the blow dry and curls and flat irons. Younger people are saying, ‘This is the hair I’ve been born with, and I’m going to embrace it.’’’Julie Ouandji, raised in Cameroon and France, hopes to discourage African women from straightening their hair through her social media website, NappyFrancophones. Ouandji, 38, founded it to write about hair tips and inspire Black women from French-speaking countries to go natural after she quit relaxing her coily hair almost a decade ago. She had read early studies questioning the health effects of chemicals in relaxers.

Today NappyFrancophones has 218,000 followers on Instagram and 85,000 on Facebook.

“I love this name because it's like being natural and happy,” Ouandji said of the word nappy. “I want to encourage Black women to love their hair and be happy about their hair. So, that's why this name was meaningful to me.”

“I was like, ‘I’m not sure it’s going to suit me,’” she said, reflecting on how her definition of beauty was synonymous with straight, long hair. “It’s really interesting to feel that way when I think about it. It’s your natural hair. Obviously, it’s going to suit you.”

As a girl, Ouandji was influenced by the women she saw on French and American TV, none of whom had natural hair.

“I think it's really important for our generation to have more Afros in the media so our daughters and granddaughters will want to keep their natural hair,” said Ouandji, who has a three-year-old daughter.

“I would like all women to stop relaxing their hair,” she said. “But that’s utopia.”

Additional reporting by Blessing Oladunjoye from Nigeria’s BONews

The Examination is a new nonprofit newsroom that investigates global health threats. Sign up to get The Examination’s reporting in your inbox.

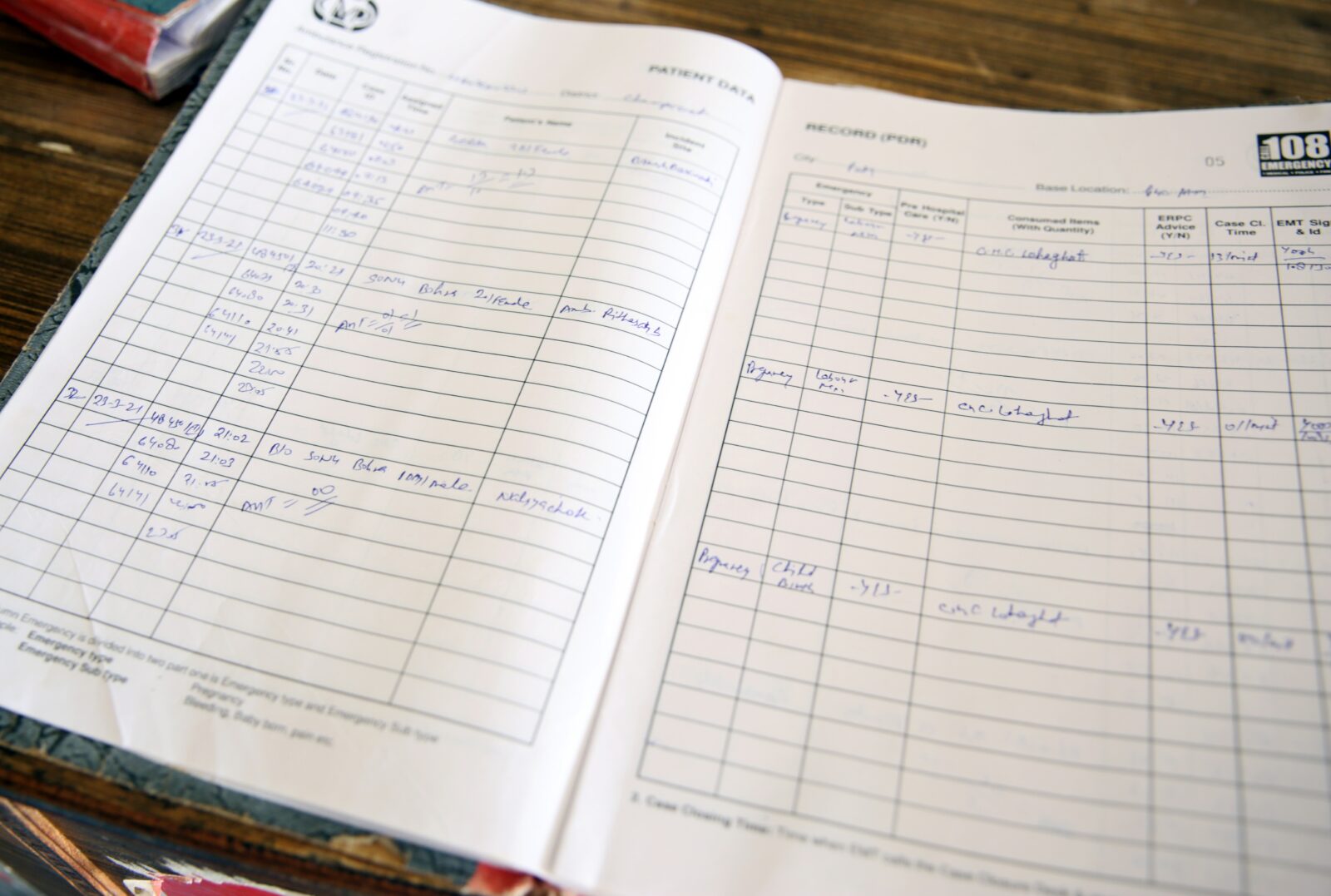

Sonu Bohra’s first pregnancy coincided with one of the longest dry spells she had seen in her home village, high in the Indian Himalayas. By the time she went into labor, it hadn’t rained for almost six months and the taps had run dry for days.

When her waters broke, an ambulance came to take her to the medical center in the nearest town. But they refused to admit her, saying they’d run out of water. The ambulance driver decided to take her to the next center, 55 kilometers away – a drive of several hours on the poor roads. But when they arrived, they discovered the same problem. They set off for the next health center, but it was too late – the baby was coming. In the end, Bohra gave birth by the roadside, helped by the ambulance driver.

As she watched her healthy two-year-old son playing and shrieking with joy outside their home, Bohra recalled the excruciating pain she endured giving birth to him. She knows it could all have ended very differently.

“I was terrified,” she says. “Other pregnant women have died. Everyone knows that these [maternal] deaths are high in this area. When the first hospital said no, I was worried that I might end up dying as well, like the others I’ve heard about. I started praying. My biggest concern was that the child inside me should remain alive and well.”

For nearly two decades, India has been working to transform its record on maternal health. It has expanded maternity units in rural areas, provided free ambulances to ensure women can get to them safely, and set up a vast network of community health workers known ASHA (Accredited Social Health Activist) workers to provide advice, organize antenatal check-ups and coordinate transportation to hospital when women go into labor.

The proportion of women delivering their babies in hospitals or clinics rather than at home has more than doubled, from just over 40 percent in 2005-06 to nearly 90 percent in 2019-21. India’s maternal mortality rate (MMR) has dropped from 400 deaths per 100,000 births in 2007-09 to 97 per 100,000 in 2018-2020, meeting a government target to bring it below 100 by 2020.

It’s one of the country’s biggest public health victories of recent decades and has won international praise. Yet as Bohra’s experience shows, the strategy of encouraging institutional deliveries has hit an unexpected hurdle – climate change.

India has 18 percent of the world’s population and just 4 percent of its water resources, according to the World Bank. It is the world’s largest user of groundwater, exceeding the U.S. and China combined, according to a United Nations report published in October that warned its north-western region would experience critically low groundwater availability by 2025.

As a changing climate has brought more erratic rainfall patterns that are less easy to predict than they were, water shortages have made it impossible for hospitals in drought-hit parts of the country to operate year-round. Even in major cities, some are having to delay planned surgeries during the driest times of the year – the hot months ahead of the monsoon rains, when water reserves run low. And unlike a planned surgery, labor cannot be postponed.

In 2019 the southern city of Chennai – home to about 5 million people – came close to completely running out of water, threatening essential services and forcing authorities to bring supplies in by train.

In mountainous areas like Uttarakhand – the north Indian state where Bohra lives – the problem is particularly acute because the terrain makes it challenging to build and maintain infrastructure like water pipes or truck in water by tankers, according to Parmanand Punetha, chief engineer at the Uttarakhand water department.

The main hospital in Uttarakhand’s Champawat district has struggled for years with water shortages. The main aquifer that its piped water supply comes from dried up at the height of the summer, when it has to rely on supplies coming in by truck. The hospital needs 25,000 liters of water a day, but the trucks only deliver about 10,000 a day, if they get there at all – sometimes they are blocked by landslides. A new pipeline was installed this year that draws water from a different aquifer. But with extraction outpacing the rate at which these underground sources naturally replenish, that will not last forever. “More springs are running dry with every passing year,” says Punetha.

On a hot day during this year’s dry season, a long queue of pregnant women were waiting to be seen. Rukmani Devi, 33 and six months pregnant, said she usually found the washrooms at the hospital were closed. “I really worry about giving birth here,” she confided. “There’s nowhere even to wash yourself after giving birth.”

The hospital’s Chief Medical Officer Dr KK Agarwal says he’s aware of other cases like Bohra’s, but couldn’t put a figure to it. “We have been raising this issue [water supply] with the authorities for years now,” he said. “Any project that needs government approval has to go through a long chain of paperwork for approvals… It takes time.”

With no data showing how often water-related maternity ward closures occur, it is difficult to know how many women have been impacted. But there is anecdotal evidence that it is happening elsewhere in India as overexploitation of groundwater has led the water table to drop, making it harder to source water during the summer.

Dr Rakesh Kumar heads a small government health center in the eastern state of Bihar that relies on water deliveries by tanker during the dry season, but receives far less than it needs to operate at full capacity. The center has been forced to turn women away fearing infection if hygiene standards cannot be maintained.

“We perform a minimum of 200 deliveries a month here,” he said. “But during peak summers, the centre receives only one water tanker a day. Most days we have to ask patient’s attendants to bring water from the nearby hand pump, or are forced to send them away for delivery if we cannot manage to get water.”

In neighboring Jharkhand state, one health worker said her local primary healthcare center had suffered consistent water shortages in recent years. “The submersible pump at the health centre stopped working a few years ago as the ground water dried up,” she said. “The washrooms are never open. Women here now prefer to deliver babies at home. We have to spend a lot of time and energy convincing them to go to the nearest hospital for delivery.”

Dr. Margaret Montgomery, the World Health Organization’s lead on water, sanitation and hygiene in healthcare facilities, said closed washrooms would put women off going to health facilities. “If toilets do not work, women do not want to go to a facility; this is a real disincentive,” she said. “India has made huge gains in reversing MMR but climate change and missed indicators into national health system monitoring and unsystematic review into budgeting will compound health risks for mothers and newborns.”

Globally, 16.6 million women give birth in hospitals and clinics every year without adequate water, according to WaterAid. The international charity’s advocacy advisor for health Annie Msosa said that more than 11% of all maternal deaths and 26% of neonatal deaths can be attributed to unclean births. “Every two seconds, a woman gives birth in a facility without adequate water. Yet, there does not appear to be specific data regarding maternal health, even though the World Health Organization (WHO) resolved in 2008 to do more research on the impact of climate change on health,” she said.

Even where hospitals have adequate supplies, water shortages are impacting pregnant women’s ability to access care. Hospitals in drought-affected parts of Kenya have recorded a drop in deliveries as local nomadic or semi-nomadic communities have deviated from their traditional migration patterns in search of pasture for their livestock, taking them further away and making it harder to get to hospitals on time.

Dr. Antony Apalia, who heads the government’s health work in the worst-hit county of Turkana in northwestern Kenya, said that during the worst of the drought this year, only around one in four births there were attended by a registered nurse – well below the 70 percent recorded in October 2022.

To address the problem, authorities in arid and semi-arid areas of the country have deployed mobile health facilities using vans or even camels. They are also using chips placed in the bracelets that young women traditionally wear to track the location of new and expectant mothers and try to ensure they can access pre- and antenatal services.

In India, reducing maternal mortality remains a key policy goal, as does the impact of water shortages. But the connection between the two has received little attention, experts say. A 2019 report on water management by India’s public policy think-tank noted that at least 200,000 Indians die every year from the lack of sanitation that results from water shortages, yet its main policy focus was agriculture. Maternal healthcare was not mentioned.

“We keep hearing news reports of how a pregnant woman miscarried while carrying water home or was refused admission due to shortage of water. Yet, there is no comprehensive analysis,” says Anant Bhan, a global health researcher in bioethics and health policy.

If current trends continue, India will not meet the global target of bringing maternal mortality below 70 per 100,000 live births by 2030, warned the WHO’s Dr Montgomery.

“The problem of maternal and newborn mortality caused due to inadequate water can be solved. It’s just a matter of political will and leadership,” she said. “But if we go by the current trends, the world will fall short in ending preventable maternal mortality by more than 1 million lives.”

With additional reporting by Allan Olingo in Kenya

KERICHO, Kenya, and SAVAR, Bangladesh—Rose Nyunja was just 18 when she began working in the tea plantations of Kericho, Kenya’s biggest tea-growing region and a major source of employment for poor women in the country. For decades, she toiled away in the tea gardens, picking the leaves by hand.

Then came the harvesting machinery. Women like Nyunja started to lose their jobs by the thousands to machines that could each replace more than 100 workers.

One evening in 2020, Nyunja returned to the staff quarters to find her front door barricaded. She’d been fired. Nyunja pleaded with her supervisor to save her job — and her home. Instead, company security ejected her from the compound.

“My 26 years of service meant nothing to them,” she says, fighting back tears. “I was given one hour to remove my household items and leave. I have never experienced such humiliation and embarrassment in my life. I worked diligently for over two decades and what have I got? Nothing.”

As Kenya’s tea estates automate to improve productivity, workers like Nyunja represent a broader global trend: women are more likely than men to lose their jobs. A 2019 study from Britain found that 70 percent of jobs at high risk from automation are held by women. And this April, a University of North Carolina study found that almost 80 percent of the female workforce in the US will be affected by advances in generative artificial intelligence, compared to 58% of men.

While recent advances in generative AI have sharpened concerns about loss of jobs for white-collar workers, job losses due to companies ramping up automation have been taking place for years, as seen in Kenya. Kweilin Ellingrud, a director at McKinsey Global Institute, says her research shows that automation is fourteen times more likely to impact low-wage workers than high earners.

“I think the reason it’s grabbing headlines is because it is also affecting higher wage jobs for the first time,” says Ellingrud. “I think now generative AI is focusing and impacting jobs across the spectrum — it affects your job, it affects my job. Some of us, myself included, aren’t used to thinking: ‘How will my work have to change? How will my job change?’”

In Kericho, Roselyne Wasike, a tea picker, says her income has fallen by almost half, from $150 a month to $80 a month, as the machines take over larger shares of work on the plantation. Even those who have managed to keep their jobs cannot escape the impact of automation. Many of them are widows and single mothers.

“These machines have disadvantaged women by making them redundant instead of giving them other tasks within the tea estates,” Wasike says.

The Kenya Plantation and Agricultural Workers Union says that 30,000 women have lost their jobs as a result of automation in the past five years. About 60 percent of the 75,000 workers currently employed in the tea sector are women, down from an estimated 75 percent in 2017, according to Dickson Sang, the secretary-general of the union.

The resentment towards the machines boiled over into violence this May. Kericho residents torched nine harvesting machines worth $1.2 million in a plantation owned by Ekaterra, the producer of Lipton and TAZO teas. The clash resulted in two deaths and the arrest of Kericho’s governor. Ekaterra suspended operations for two weeks, leaving more than 16,000 employees without work.

One of the areas of dispute had been a provision in the industry’s collective bargaining agreement that workers, most of whom are women, would be kept on as machine operators. Labor leaders say multinationals have “flatly refused” to implement this.

“I do not condone the destruction of property. But these workers are now fighting back because the tea firms keep moving the goalposts,” says Sang.

Ellingrud says 85 percent of jobs impacted by generative AI will be concentrated in four job categories: food services, customer service and sales, office administration, and manufacturing. The first three are dominated by women. Even in manufacturing, women workers like Nyunja are vulnerable compared to men, who have a higher chance of being re-trained for roles involving automation.

The COVID-19 pandemic showed that women are more likely to lose jobs during periods of economic upheaval, and are slower to return to the workforce, Ellingrud says: “Women’s unemployment is more sticky.”

Her research at McKinsey has found that 12 million people will need to switch jobs by 2030, and that women are 1.5 times more likely than men to have to change their occupation. She says this means governments and businesses need to urgently take targeted actions to re-skill and up-skill women.

Automation has also radically changed the make-up of Bangladesh’s garment industry, once hailed for transforming women’s employment prospects. Women once made up over 80 percent of the garment workforce today they account for less than 60 percent. In 2019 the government projected that half a million garment workers, mostly women, would lose their jobs to automation.

At Moni Garment and Training Center in Savar, a garment hub north of the capital Dhaka, Mizanur Rahman drills his trainees on how to operate machines used for weaving and knitting. A former garment worker himself, he says being sensitive to small areas of concern goes a long way towards making women feel more comfortable.

This includes hiring female instructors for female trainees and offering flexible hours so that women can show up before or after taking care of household chores. He says the confidence women gain from their training can lead to increased recognition at work.

“Many of my trainees perform well and are promoted to supervisor or line chief positions,” Rahman says.

Supervisory roles and roles operating automated technology are likely to be among the key jobs that survive in a post-automation landscape. Both tend to be dominated by men. In Bangladesh’s garment industry, women have long made up less than 5 percent of supervisors despite being a significant majority of the workforce.

There have been some signs of success. The Gender Equality and Returns project, run by the World Bank’s International Finance Corporation and the International Labor Organization, says 60 percent of its trainees have been promoted to supervisory positions, and the number of female supervisors in the industry has jumped to 12 percent since the program began in 2016.

Abdullah Hil Rakib, a director at the Bangladesh Garment Manufacturers and Exporters Association, the country’s largest trade association for the industry, says the key obstacle to women thriving in supervisory or machine operator roles is psychological.

“It’s a barrier in our mindset,” he says. He points out that automation means less physically strenuous work for both men and women, eliminating one barrier that would have previously made some jobs less accessible for women.

“Even when a man runs a heavy automatic cutter machine, he only pushes a switch on and off. He does not need to do more,” Rakib says.

Ellingrud says about 10 percent of jobs created every year tend to be new roles that didn’t exist before, but women take up these jobs at a lower rate than men. People won’t be losing their jobs to AI, she says, but to people who know how to use AI; women who are unable to adapt risk being left out of the new economy.

Adaptation feels like a distant prospect in Kericho, where Nyunja hawks vegetables on the street to make ends meet.

“I used to be able to take care of my family and pay my children’s school fees,” Nyunja says. “Now my future looks bleak. I can barely pay my rent, let alone send my child to school.”

Maher Sattar contributed reporting from New York.

Pilot Lenaigwanai covers her mouth as she speaks. She is trying to hide her broken tooth, a bitter reminder of all she endured before finding refuge at a shelter for abuse survivors in northern Kenya.

The mother of three arrived here in July after being forced from her home by escalating violence. Her husband was abusive even before the drought that’s now ravaging Kenya’s arid north, the worst in decades. When the family’s 68 cattle — their only means of survival — died, the abuse became impossible to bear.

“He was visibly frustrated and turned the heat on me and my children,” she says. “I just think he wanted us out, because he could not provide for us anymore.”

Lenaigwanai is one of the dozens of women who have arrived at the Umoja refuge in recent months fleeing violence that they say got worse as each successive year of low rainfall plunged their families deeper into poverty. Her semi-nomadic Samburu community of pastoralists are particularly vulnerable to drought because they depend on the livestock whose emaciated corpses litter the barren lands that once provided plentiful grazing.

For these and many other women around the world, the threat of violence could become more common as climate change makes extreme weather events more intense and frequent.

Scientists have long warned that climate change disproportionately impacts the world’s poorest and most vulnerable, and negotiators from wealthy countries at the U.N. Climate Change Conference in Egypt pledged to do more to help poorer countries already grappling with its devastating effects.

Until recently, relatively little attention has been paid to its disproportionate impact on women and girls. But this year the U.N. Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change identified a link between climate change and violence, citing the growing evidence that extreme weather events are driving domestic violence, with global implications for public health and gender equality.

A 2021 study of extreme weather events in Kenya by researchers at St. Catherine University in Minnesota found the economic stresses caused by flooding and drought or extreme heat exacerbated violence against women in their homes. The research, which used satellite and national health survey data, showed that domestic violence rose by 60 percent in areas that experienced extreme weather.

That analysis, and 40 others published this year as part of a global review in the journal The Lancet, found a rise in gender-based violence during or after extreme weather events.

Terry McGovern who heads the department of Population and Family Health at Columbia University’s Mailman School of Public Health, called the scientific evidence for this connection “overwhelming.”

“Heat waves, floods, climate-induced disasters increase sexual harassment, mental and physical abuse, femicide, reduce economic and educational opportunity and increase the risk of trafficking due to forced migration,” said McGovern, who added that the data remains limited on some fronts, including on psychological and emotional violence and attacks against minority groups.

Several academics, activists and humanitarian workers said the links between violence against women and extreme weather events need more research. Unlike the hard science of climate change, they said, the complex drivers of violence cannot easily be captured in numbers.

“The climate discourse is all about the numbers, but the evidence on violence and changes in power dynamics cannot be captured that way, and so it is not given the same weight,” says Nitya Rao, a professor of gender and development at the University of East Anglia in the U.K. “It is very difficult to make a linear connection.”

In Umoja, no one is in much doubt that the drought is driving up violence — its swelling numbers are proof enough. Jane Meriwas, whose nonprofit organization the Samburu Women Trust helps women who have fled abusive homes support themselves, says the number of women at Umoja has doubled to 51 in the last year.

“As communities and families lose their livelihoods and suffer hunger, there is increased experience of weak or broken family structures,” Most are now engaging in dangerous activities to get a meal,” she said, such as sex work and bootlegging.

With their semi-nomadic lifestyle, Samburu women are particularly vulnerable. They have little or no stable access to health facilities, police protection or support services, Meriwas said, making it harder for them to report abuse. “They are really suffering in silence.”

‘The violence peaks during the floods’

In eastern India, more frequent downpours and devastating floods are what’s driving violence. Poverty is exacerbated by sudden economic stress, and societal inequality often traps women with abusive partners or other family members because they have nowhere else to go and cannot rely on authorities for help.

A mother of five who asked to go by her middle name, Devi, to protect her identity, said she doesn’t know anything about climate change. She just knows that whenever floods come to her village in Bihar state, her husband comes home angry and violent.

With her husband working away from home much of the year as a farm hand, each season can be challenge. But the monsoon season, Devi said, is by far the toughest. That is when the rivers in her low-lying village downstream from the melting Himalayan glaciers swell to bursting, flooding large swaths of land and making farming impossible. With no prospect of work until the floods recede, her husband returns home and takes his frustration out on his family.

“The violence peaks during the floods. Everything gets worse at that time — the hunger, the stress. We have snakes coming into the house,” says Devi, 40.

“The anger gets taken out on me. There’s a lot of stress during those times and I can’t sleep because of all the tension,” she says, wiping away tears as one of her young sons leans in closer.

Devi, who shares her small thatched-roof home with her mother-in-law, has little privacy to describe the nature of the violence. But when the older woman went out of earshot, she said her husband beats her and verbally abuses her “day and night” during the floods.

Shilpi Singh, who works with women in India’s poorest state as director of a grass roots organization called Bhoomika Vihar, said she sees the connection between floods and violence as straightforward.

“It comes down to economic distress. When there is no food to eat in the house, the men vent out their frustration by beating the women, who are raised with the belief that leaving is not an option.”

For Devi, the floodwaters themselves trap her. When they surround her home, they cut her and her family off from the outside world, increasing her vulnerability even further. As she talks about her situation, she repeatedly invokes a well-known Hindi phrase that translates roughly as “I endure,” which almost always refers to women’s suffering.

“If my daughters find themselves in this situation, I will tell them, they must endure,” she said. “If there are bad days, good days must surely follow.”

Lessons from a typhoon

Scientists emphasize that extreme weather events do not cause domestic or gender-based violence, but instead exacerbate existing pressures or make it easier for perpetrators to carry out such violence.

The mass displacement that follows disasters can expose women to greater danger, according to studies in Bangladesh and parts of India.

The Philippines ranks as one of the world’s most disaster-prone countries, suffering frequent earthquakes and storms that are becoming more intense as the world warms. Nine years ago, Typhoon Haiyan — one of the strongest cyclones ever recorded — flattened entire villages in the Philippines, killing more than 6,000 people and displacing around 4 million.

When Typhoon Rai hit the Philippines in December 2021, the country was better prepared. The relatively low death toll — in the hundreds — has been attributed in part to improved early warning systems and other measures put in place by local authorities. But it caused nearly as much property damage as previous storms. Just over a year later, many victims are still living in makeshift shelters after losing their homes, and in many cases, their crops and livelihoods.

Rommel Lopez, spokesperson for the local social welfare department, said these stresses often acted as triggers for abuse within families in a country where violence against women is common. One in every four Filipina women aged 15 to 49 has experienced physical, emotional or sexual violence from a husband or partner, according to a 2017 demographic survey conducted by the Philippine Statistics Authority.

“When there’s a calamity or disaster or conflict, that can put families in difficulties. The situation at evacuation centers is a contributing factor,” Lopez said. “It makes them agitated. It adds to their frustration. When someone is frustrated, they could reach a certain point and that could trigger [violence].”

Aira Nase, 37, has been running away from violence all her life. Her mother suffered beatings from her partner and as a young girl, Nase vowed never to be like her. She was proud of raising her three children alone, taking on jobs in Manila, the capital, to provide for them.

When covid hit in 2020, she decided to leave the city and take her family back to her home province of Southern Leyte on the eastern side of the archipelago that makes up the Philippines. She got together with a local fisherman, and for a time the couple enjoyed a quiet life. They would occasionally quarrel over his drinking, particularly after Nase became pregnant in 2021, but never got into physical fights.

All that changed after Typhoon Rai made landfall shortly before Christmas 2021, devastating swaths of the country and destroying the couple’s home. They spent the holidays in a school library that doubled as an evacuation site, remaining there until May.

Her partner began drinking more frequently and the couple fought daily. Then Nase’s breast milk dried up, but the couple could not afford formula for their two-month-old baby. Her 16-year-old daughter gave birth to a premature baby who died after they could not afford hospital care.

The tensions between the couple peaked in February, when Nase’s partner returned drunk and rowdy to the library, disturbing other evacuees. Nase said she tried in vain to quiet him down. When she went to leave, he kicked her before rushing out of the room. Nase passed out and when she regained consciousness the next day, he was in jail.

“It was a very stressful time for us. We were broke and jobless. He was hotheaded and often drunk,” Nase said. “I told him: you’re not the only one who suffered from the storm, our neighbors did too. If you have a problem, why don’t you talk to me?”

There’s no official data showing how extreme weather disasters affect levels of violence against women and girls in the Philippines. One study, based on in-depth interviews with 42 people including survivors of Typhoon Haiyan, aid workers and government officials found reports of domestic violence, sexual violence and incest had increased in its aftermath. A separate survey of more than 800 households in the affected area carried out by the International Federation of the Red Cross and Red Crescent Societies (IFRC) found increases in both early marriage and domestic violence.

Humanitarian organizations working in the Dinagat Islands, which were badly hit by Typhoon Rai, sought to break this pattern. They launched a poster campaign highlighting where women can go for help if they are facing violence at home, along with a phone number to call.

For the Samburu women at Umoja, escaping the twin pressures of violence and drought has become key to their survival.

Rose Lairolkek sat in the little remaining shade afforded by the cluster of traditional mud-roofed huts that make up the refuge. She recounted how her husband came home angry after discovering all his cattle had died and attacked her, and how she still bears the scar on her right shoulder more than two years later.

“It almost cost me my life.”

Related Stories:

Lessons from Texas: Advocates Warn of Extreme Weather’s Link to Domestic Violence

DANDORA, Kenya– As Winnie Wanjira rifles through mountains of waste at the Dandora dump in Nairobi, it’s not the discarded needles that most bother her. Nor the metal scraps that could shred her skin like paper. It’s not even the hot sun that beats down on the rancid rubbish, making the 36-year-old feel so dizzy she struggles to fill her sack with plastic bottles.

Today, the mother of six is anxious about her period. It’s heavy, she says. So heavy she spent the last two days lying down in her windowless, single-bedroom home, unable to move. “The bleeding… is no joke,” she tells The Fuller Project and VICE World News. “I cannot come to work, I cannot go anywhere.”

Now, on the third day, she’s back, hoping the jumper tied around her waist will cover any stains. “And it’s, like, black, not even the normal colour of periods,” she says. “That place… It kills. It really kills.”

As far back as 2007, the United Nations Environment Program warned that Dandora posed a serious health threat to those working and living nearby. Yet while it is understood that exposure to the toxic chemicals found on dumpsites can result in cancer, respiratory problems and skin infections, scientists and environmental campaigners say relatively little attention has been paid to their impact on the reproductive health of waste pickers, who are often women. Materials such as plastic and e-waste contain a cocktail of chemicals that studies show can disturb the body’s hormone systems. As ever-higher volumes of trash continue to end up in landfills, informal workers like Wanjira will be on the front lines of what scientists are calling an emerging issue of global concern.

For years, acrid smoke has billowed across this sprawling dumpsite, which covers an area of the Kenyan capital the size of 22 football pitches. On windy days, clouds of smoke engulf the nearby neighbourhoods. “You can’t breathe,” a woman who works in a nearby pharmacy tells The Fuller Project and VICE World News.

It’s not just an issue at Dandora. Across Kenya’s dumpsites, a potentially toxic mix of everything from empty milk cartons to old tyres are being destroyed through open burning, according to a 2017 report by the government and the United Nations. Around the world, many of the estimated 20 million waste pickers in countries such as India, Ghana and Vietnam likely face similar health concerns. Estimates vary, but studies show this informal workforce is often mostly women.

“This is a global problem,” says Griffins Ochieng, executive director for the Centre for Environmental Justice and Development (CEJAD), a Nairobi-based nonprofit focusing on the problem of plastic waste. “Any dumpsite – anywhere there is plastic pollution – women will be impacted.”

This is because many materials that end up as waste contain toxic substances. Plastics and e-waste are known to contain and leach hazardous chemicals into the environment, including endocrine-disrupting chemicals (EDCs), which have been linked to reduced fertility, pregnancy loss and irregular menstrual cycles, among many other conditions. Burning them releases or generates a number of highly toxic chemicals and heavy metals, with reported similar effects. The toxins are not only in the air but also in the soil and water, and for the many waste pickers who eat from the landfills, in their food, too.

While men frequently take on more supervisory roles, women often spend the entire day rummaging, says Ochieng. “They’re in the thick of things… but the environment is a threat to their human health.”

Globally, the amount of trash we produce – and where to put it – is a growing problem. Each year, the world generates 2.01 billion tonnes of household waste, the equivalent of more than 6,000 Empire State Buildings being collectively chucked out every 12 months. By 2050, the number is set to rise by more than 70 percent. In low-income countries, over 90 percent of waste is either dumped in the open or burned.

It’s why waste pickers, like Wanjira, are often described as the backbone of waste and recycling industries. They’ve stepped in, an informal, often invisible workforce relied upon by governments in parts of Latin America and Asia and across Africa. Spending long days bent over, picking up and sorting waste discarded in streets and dumpsites, they recover more recyclable materials than formal waste management systems yet represent some of society’s most marginalised populations. In Kenya, roughly 3,000 to 5,000 waste pickers scatter across Dandora’s hills every day. Around the country, local organisations estimate the numbers reach nearly 50,000, although there is no official total.

If Wanjira’s heavy, painful period had been a one-off, she might have been a little less worried. But she’s faced the same issue – often twice a month – for roughly 20 years, she says. When Wanjira was about 13 and her family could no longer afford school fees, she dropped out and started working with her mother, Jane, who was also a waste picker. Within several years, Wanjira’s problems with her menstruation started, she says.

She’s not alone. In interviews with 32 women across Dandora and Gioto, another vast dumpsite in Nakuru, a three-hour drive from Nairobi, 21 women said their periods are irregular. Many, like Wanjira, face very heavy, painful periods once or twice a month. Others wait eight months for theirs. One in three say they have suffered serious issues when pregnant, including miscarriage, stillbirth and premature birth. About 10 to 15 percent of pregnancies worldwide end in miscarriage, according to March of Dimes, an organisation that works on pregnancy and postpartum health, while stillbirth and premature birth are much rarer.

One 59-year-old woman who has worked at Dandora for nearly three decades is being treated for uterine cancer.

“We hear these issues all the time,” says Joyce Wangari, a 23-year-old waste picker who has worked at Dandora since she was 12. She only gets her periods every two to three months. “It’s so common.”

There’s no definitive proof that the problems experienced by these waste pickers are caused by exposure to toxic chemicals, but it’s highly likely to be an underlying factor, according to Sara Brosché, science adviser at the International Pollutants Elimination Network (IPEN), a global network dedicated to eliminating toxic chemicals.

“The evidence is strong,” she says. “But the connection between toxic chemicals and impacts on women hasn’t really been talked about that much. It’s such an important but overlooked issue.”

In WhatsApp messages, Daniel Wainaina, chief officer for public health at Nakuru County, says waste pickers’ health is not individually analysed but that it would be “an interesting area for prospective studies.” He did not answer specific questions about the impact of toxic chemicals on reproductive health.

Neither the Nairobi county government nor the national governing body that oversees environmental policies replied to multiple requests for comment.

Doctors in several medical clinics near the dumpsites point out the workers’ choice of family planning likely plays a significant role. Many birth control options, including the pill, implants and intrauterine devices (IUD), can produce menstrual cycle changes. Genetics, nutrition and poor living and working conditions may also play a part. Most waste pickers handle trash without gloves or masks, and they often live near or on the dumpsites, which intensifies their exposure to health risks.

Yet one-third of those interviewed say a medical professional informed them their reproductive health issues either were or could be connected to their working environment. Some started picking trash as adults, and say they had no reproductive issues before then. Others say they aren’t using any contraception, or their problems persisted after they stopped taking the pill or removed the implant. Several say they started taking hormonal contraception with hopes of regulating their menstruation – often with little success.

“Before I came here, my periods were normal,” says one waste picker, whose name we are withholding due to safety concerns. “But then it came heavy, and so many times in a month.” She began picking trash when she was roughly 30 years old. Now 58, she is no longer menstruating, likely due to menopause. “But that smoke enters your body. You feel weak, so weak.