A state fund designed to financially support victims of violent crimes in New York has distributed money to only a small fraction of those eligible, a new report has found.

The New York City-based nonprofit Common Justice, which works to promote alternatives to incarceration and helps to support victims of crimes, determined that during the 2018-2019 fiscal year, the state Office of Victim Services (OVS) awarded just 6,140 compensation claims, covering a small fraction of all violent crimes. In 2019, nearly 70,000 violent crimes were reported in New York State.

The Office of Victim Services covers costs for victims who have no other resources or have exhausted all of their other options, such as health insurance, workers compensation or car insurance.

The compensation fund is intended to fully reimburse victims for services like mental and physical health care, but also pays a set amount for other costs, like funeral arrangements.

To qualify for the compensation, one generally has to have experienced or lost a family member to physical violence. Applicants also must not have contributed to the crime, and must have reported the incident to law enforcement. According to Common Justice, those restrictions, as well as a slow and strict bureaucracy, make it hard for many victims to access compensation.

Meghan Van Alstyne, 36, learned firsthand two years ago how difficult navigating that bureaucracy can be after an enraged driver attacked her on her way home from her shift as a volunteer medic at a Black Lives Matter rally in Albany.

The driver, angered by a perceived slight on the road, pulled in front of Van Alstyne’s car, got out, and struck her across the face with a metal carjack. Van Alstyne convinced him to go back to his car, but her injuries were extensive.

“I broke most of the molars on the left side of my face, and I had a puncture wound through my cheek that required a dozen stitches to close,” she said. At the hospital, she recalls having to poke her fingers through her face to prove to the doctors that she wasn’t just being “emotional” and that her injuries were severe.

In addition to the damage to her face and teeth, Van Alstyne developed a traumatic brain injury that caused everyday stimuli to become painful. “I spent the better part of three months pretty much with no light, no sound,” she said. “It was a pretty difficult recovery, especially to do during a pandemic.”

The responding officer at the scene of her attack, in the city of Troy, inaccurately told her she’d have to wait until her assailant was apprehended to apply for victims’ compensation. Van Alstyne ended up waiting months before seeking help from OVS.

“It was an incredibly slow process to get all of my paperwork filed,” she said. And then, she found, the delays compounded as her payment requests got denied. “I ended up having to escalate my application through OVS multiple times because I was repeatedly rejected for medical funding and interventions.”

At one point, she said, the office rejected paying for the extensive mental health treatment she needed to cope with the attack because, during the pandemic, she was only able to seek online therapy. Her social worker listed the service as “subscription,” which she was told OVS did not cover.

OVS spokesperson Janine Kava did not comment on Van Alstyne’s specific case. However, the office said that since the pandemic began, they now cover telehealth services.

Van Alstyne said that OVS denied most of her dental work because she couldn’t immediately see a dentist after her attack. OVS argued that they couldn’t verify that her extensive dental injuries were due to being struck in the face.

State law only permits OVS to cover expenses directly related to the crime.

“The amount of anxiety and stress and trauma that trying to negotiate and navigate that system causes feels like a secondary assault,” said Van Alstyne, who eventually gave up trying to work with OVS after getting just $2,000 of her more than $10,000 in medical bills paid. “Frankly, my credit is trashed. Things have been sent to collections and then taken out again, and I can’t undo any of that.”

She says the ripple effects of the experience have altered the course of her life.

“I was looking at buying a house. All those things are now on hold for me,” she said. “And a lot of this is not only a direct result of my assault and injury. It’s from the red-tape and delay of working with an organization that is systematically failing.”

Unlike in most other states, New York’s OVS does not limit the amount of money a victim can seek to cover physical and mental health care expenses. But, as Van Alstyne discovered, accessing those funds is a challenge.

According to the Common Justice report, OVS denied the claims of more than 3,600 applicants during the fiscal year 2019-2020. Over that same time period, OVS made a total of 9,912 claim decisions.

Kava, the OVS spokesperson, said it’s important to note that decisions about awards as well as payouts for claims occur on a rolling basis. Decisions can also change once additional paperwork is provided over the same fiscal year, they added, making it difficult to compare “no-award” decisions against the total number of decisions made within a given year.

Off the Radar

According to Common Justice, many victims don’t even know that applying for compensation is an option.

“At least 90 to 95% of clients we see have not heard that OVS services exist,” said director of outreach Lauren Lipps in the report.

Margarita Guzman, a domestic violence survivor and executive director at VIP Mujeres, an organization that works with Spanish-speaking survivors of domestic and sexual violence in New York City, said that she wasn’t aware of the program until she started working with survivors.

“Even as a lawyer: Pretty educated, able-bodied, English proficient. I did not know that it existed,” Guzman said.

But Guzman added that awareness is not enough for her clients at VIP Mujeres, many of whom are undocumented immmigrants — and therefore may hesitate to report crimes, which is one of the requirements set by OVS. “We work with a community that really measures their good fortune by being off the radar of most authorities,” Guzman said.

Proposals pending in Albany would for the first time allow victims to get aid from the fund even if they didn’t report the crime to law enforcement. The bill, sponsored by Sen. Zellnor Myrie (D-Brooklyn) and Assemblymember Demond Meeks (D-Rochester), would remove the mandatory law enforcement reporting requirement and enable victims to provide alternative forms of evidence to show that a qualifying crime was committed.

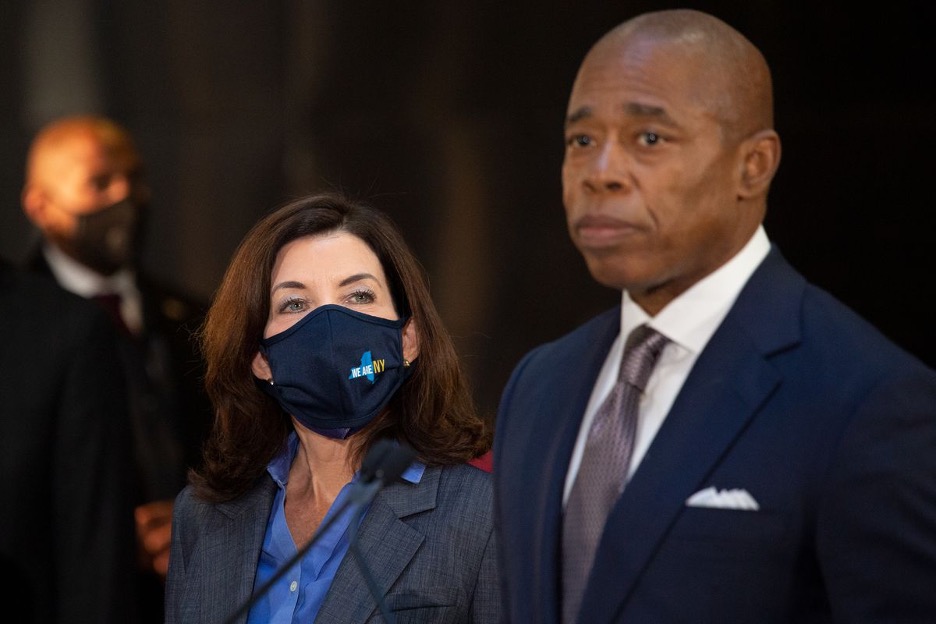

When asked by THE CITY and the Fuller Project where they stand on the proposal, neither Gov. Kathy Hochul’s office nor the NYPD stated a position. Guzman said however that taking law enforcement out of the equation would be a game-changer for her clients.

“To extract victims’ compensation from law enforcement completely shifts the character of what this resource is,” Guzman said. “And I think it really shifts the willingness of community members who are unwilling to engage with law enforcement to have more of their needs met.”

Survivors of gender-based and domestic violence may be in a similar situation, said Alice Hamblett, one of the report’s authors. “Many [survivors] fear that calling the police would make things worse… or they won’t be believed,” she said. “Reporting to police can be a big barrier for women, and anyone who experiences intimate partner and domestic violence from accessing victims’ compensation funds.”

For now, those who seek victims’ compensation must report to law enforcement within a week of the crime, with some exceptions. According to the report, this can put a lot of pressure on survivors who are also dealing with the trauma of what’s happened to them.

The victims’ compensation fund typically requires survivors to have suffered physical violence. However, there are several exceptions, including for victims under the age of 18, over the age of 60, and targets of certain crimes like stalking, harassment, and kidnapping.

Left out are survivors of domestic violence who have endured psychological or emotional abuse, Hamblet said.

“People who experienced these particular types of violence not in conjunction with physical violence or maybe aren’t reporting in conjunction with physical violence don’t necessarily get the victim compensation that they deserve,” she said.

Common Justice also says racial bias can play a factor in determining who is granted compensation.

The concept of “contributory conduct,” the idea that the victim took part some way in the crime, opens the door for police and OVS officers to make racially discriminatory guesses about the inherent criminality of the victims, said Oresa Napper-Williams, executive director of Not Another Child, an organization focused on ending youth gun violence.

OVS is not supposed to deny families compensation based on previous gang activity or racially biased assumptions about previous gang affiliation. However, state regulations require OVS to consider current gang activity when determining contributory conduct.

“I have seen parents denied victims’ compensation a lot of times because the detective on the case will say he had a history of involvement with gangs,” Napper-Williams said.

Buried in Bills

Even for those who manage to qualify for victims’ compensation, according to Common Justice it’s often not enough or comes too late.

In 2006, when Napper-Williams laid her only son to rest after a stray bullet killed him, OVS awarded her $6,000 for funeral costs. “Here we are in 2022, when inflation is at its highest, everything is high, these families are still awarded $6,000,” Napper-Williams said.

She said that for families without savings, who never expected to bury their loved ones so soon, $6,000 is simply not enough. The median funeral cost in the United States in 2021 was $7,848.

Families also don’t receive the entire $6,000 right away, said Michelle Barnes-Anderson, executive director of the Melquain Janelle Anderson Foundation, which provides support for victims of gun violence. Barnes-Anderson also went through the victims’ compensation process when her son was murdered in 2017.

For folks who need to bury their loved ones or to move for their physical or emotional safety after a violent crime has occurred, the seeming lack of urgency from OVS is particularly troubling, she said.

Survivors of violence can receive a $3,000 emergency award within 24 hours of filing with OVS. However, according to OVS, it takes them an average of 107 days to award or deny a victim’s entire claim.

“[Survivors] can’t wait a month for you to mail them a check,” Barnes-Anderson said. “What are they going to do right now because with crime victims if you have a funeral situation … it takes a long time to get you that check but what are you doing in the meantime?”

According to Kava, much of the bureaucracy involved in the compensation process is required by both state and federal regulations, but officials are working to improve access. OVS is now funding 228 victim service programs housed within nonprofits and municipal agencies to help victims more easily access compensation.

“OVS has a proven track record of expanding eligibility for victims’ compensation, streamlining its claims process and improving access to services,” Kava said. “That being said, we know that barriers remain. We will continue to work closely with service providers, victims of survivors of crime, and other stakeholders to expand access to compensation while ensuring that the safety net provided by OVS remains as accessible to anyone who needs it.”

Although some direct-service providers such as Safe Horizon, a domestic violence group in New York City, can mGuzman argues that allowing community-based organizations like VIP Mujeres to make service determinations would help improve access to victims’ compensation.

“There should be an emphasis on culturally specific organizations and organizations that have buy-in from the communities that they exist to serve,” Guzman said. “So that you are getting the resources to the most trusted messengers on the ground and in a community that can reach people who need it the most, who are often the people who don’t get it now.”

Even those who are frustrated with the process of applying for victims’ compensation, like Van Alstyne, see a potential for reform.

“Overall, it’s a good program, but it needs deep attention so that there aren’t people falling through the cracks,” she said.

Correction: A previous version of this story incorrectly stated that Safe Horizon makes service approvals.

On Monday, Politico published an explosive report that included a leaked draft of Supreme Court Justice Samuel Alito’s majority opinion in a Mississippi abortion case in which he searingly repudiates Roe v. Wade, calling the decision “egregiously wrong from the start.”

Today, Chief Justice John Roberts confirmed that the draft was real, but insisted that it did not represent the final decision of the court, according to the Washington Post.

Legal experts likewise cautioned the decision is not final and that justices can change their mind or conclude that while they support upholding Mississippi’s 15-week abortion ban, overturning Roe v. Wade is a step too far.

“It’s not done inside the Supreme Court until the opinion is ready to be released,” said Stephen Wermiel, a constitutional law professor at American University Washington College of Law, “or in fact until it’s actually released.”

Nonetheless, advocates and lawmakers in New York quickly mobilized today to protect abortion rights inside the state — and to cement the state’s status as a safe haven for those around the country seeking abortions.

Here in New York City, thousands of pro-choice supporters rallied at Foley Square, many wearing green, a color that has become internationally associated with movements for safe and legal abortions.

City Council Speaker Adrienne Adams and New York Attorney General Tish James both appeared at the rally. “We will not take this lying down. We will walk, march, run to freedom — freedom for the right to choose and safe abortion access,” Adams said.

“I feel like we’re regressing as a country,” an 18-year-old protester named Alexis told THE CITY and The Fuller Project. “It’s 2022, and yet I don’t have full autonomy over my body.”

New York’s Safe Haven

Thirteen states have trigger laws which would ban abortion if Roe v. Wade is overturned, and 26 states have abortion laws on the books that are currently blocked by the courts, whose bans could be overturned if Alito’s draft opinion becomes the law of the land.

In 2019, New York became one of the first states in the nation to codify the right to an abortion. Lawmakers simultaneously ended the state’s ban on abortion after 24 weeks of pregnancy.

That same year, the New York City Council voted to fund the New York Abortion Access Fund (NYAAF), which helps low-income New Yorkers and people traveling from out of state to access abortion services.

And earlier this year, Assemblymember Jessica Gonzáles-Rojas (D-Queens) and State Sen. Samra G. Brouk (D-Monroe/Ontario) introduced legislation that would increase insurance coverage for abortion care in New York State.

However, despite, the strides New York has made in making the state a safe haven for abortion access, advocates like Sasha Neha Ahuja, who organzied the protest in Foley Square, say there’s still a lot more to be done.

“This fight is at our doorstep,” said Ahuja. “It is not something that New Yorkers can look away from and say, ‘Oh, this is happening in Texas and Alabama and Mississippi,’” she added. “We cannot turn a blind eye to what’s happening in this country. We have to be a safe place for people to access care.”

New York has long served as a sanctuary for abortion seekers. In 1970, three years before Roe was decided, the state legalized abortion, drawing hundreds of thousands of women from across the country seeking safe and legal abortions. With Roe now seemingly on the chopping block, abortion advocates and providers are readying themselves for a similar situation.

Ahuja’s suggestions include doubling down on existing laws at the city and state level, including increasing the Council’s existing spending on abortion access. Since 2020, the Council has allocated $250,000 each year for the New York Abortion Action Fund.

“New York City Council has already begun funding abortion outright,” said Ahuja. “Expanding that pot of money is a huge thing that the Council can readily do as we anticipate more and more folks seeking access to states like New York.”

At the state level, efforts are already underway to make sure New York can meet the needs of folks fleeing states with restrictive abortion laws.

On Tuesday, González-Rojas and State Sen. Cordell Cleare (D-Harlem) introduced companion bills to create a state abortion fund that would ensure that providers get resources through the Department of Health to cover the potential influx of folks coming to the state to receive care.

If the Supreme Court overturns Roe, New York State would become the closest abortion provider for roughly 190,000 to 280,000 women out of state, wrote González-Rojas in a statement.

New York’s Congressional representatives are also engaged in the fight to protect abortion rights at the federal level. On Tuesday, Democratic Senate Majority Leader Chuck Schumer (D-N.Y.) vowed to call a vote to codify Roe v. Wade into law.

“A vote on this legislation is not an abstract exercise,” said Schumer at a press conference on Tuesday. “This is as urgent and as real as it gets.”

The state’s own redistricting battles, as well as efforts across the country to shift the balance of power in Congress through gerrymandering, now take on renewed significance in light of Roe’s expected demise.

“There’s a big question mark, in terms of the you know, what the makeup of our congressional representation looks like,” said González-Rojas, in reference to the recent court decision to overturn the district maps created by the Democratic majority. “That could skew the congressional ability to fight for abortion access and reproductive justice. And, that’s why the urgency to do something is now, before we get to that point.”

As of right now, it’s important to remember that the right to abortion is still constitutionally protected, said González-Rojas, who hopes that the leaked draft will serve as a call to action for residents and legislators alike.

Calling your representatives in Congress to ask them to codify Roe and donating to local abortion funds are all ways New Yorkers can help, she said.

“This is about dignity. This is about equity, this is about justice,” said González-Rojas. “We’re gonna keep fighting.”

Correction: An earlier version of this article incorrectly identified the State Senator who introduced a companion bill as State Sen. Alessandra Biaggi (D-The Bronx/Westchester).

Tracy McCarter won a small concession from Manhattan District Attorney Alvin Bragg Monday in a case alleging she murdered her estranged husband. But the DA’s office stopped short of dropping a murder charge for an act she says was in self-defense.

Bragg has been in the hot seat for how his office has handled the Upper West Side woman’s case, after he called her prosecution “unjust” during his campaign running as a progressive prosecutor set on reducing incarceration before taking office Jan. 1.

“I #StandWithTracy,” wrote Bragg in a September 2020 tweet. “Prosecuting a domestic violence survivor who acted in self-defense is unjust.”

At a hearing on Monday in Manhattan Criminal Court, prosecutors dropped their opposition to McCarter’s request to receive in-patient mental health services in Florida under advisement from her treatment team. She has been unable to leave New York City and is under electronic monitoring after being detained for six months on Rikers Island.

Up until Monday, Bragg’s office had opposed McCarter’s request to change the terms of her bail to allow her to leave the city to receive treatment for post-traumatic stress disorder and suicidal thoughts.

Despite the prosecution’s change of heart, Judge Melissa Jackson, who presided at the hearing, denied McCarter’s request to leave the state for treatment and set a new hearing for April 5, before a different judge.

Related coverage: Do police help or hurt domestic violence survivors? New York City council members take a stand

Although it’s a far cry from having the charges dropped, the prosecutors’ actions could signal a shift in how the new Manhattan District Attorney’s office, which plans to meet with McCarter’s defense team in the next two weeks, is approaching the high-profile case.

In court documents, McCarter, 46, and her legal team provided evidence that Murray got violent when he was drinking, and alleged that he once put her into a chokehold. McCarter declined to comment to THE CITY or The Fuller Project.

The grand jury that indicted McCarter under former District Attorney Cy Vance never heard about Murray’s alleged history of violence, or her claim that she was acting in self-defense. Judge Jackson later ruled that the grand jury was not required to know that information before making their decision.

If she’s convicted, McCarter — who welcomed her first grandchild while at Rikers — faces 25 years in prison.

Supporters of McCarter’s have been waiting for any sign that Bragg might decline to continue prosecuting her case.

Bragg’s office did not respond to requests for comment.

His silence since his election has deeply troubled McCarter’s supporters and family members, who say they feel misled.

“It feels like a bait and switch,” said Ariel Robbins, McCarter’s daughter. “You said that you don’t believe in her being prosecuted, and yet your office is prosecuting her, so what’s changed between then and now besides the fact that you’re in power?”

Wearing a ‘shackle’

When Bragg won, Robbins remembers feeling an overwhelming sense of joy because of the statement of support he made publicly. “To have him win felt like, wow, this is going to be over,” said Robbins. “This nightmare we have all been living for way too long, it’s finally going to be over.”

Instead, McCarter remains confined to New York City, and must wear an electronic ankle monitor, which Robbins refers to as her “shackle.”

Because her charges show up on a background check, she’s been unable to return to work as a nurse. And the judge’s ruling means that at least until April 5, she likely won’t be able to receive in-patient care, which has been recommended by her medical team.

Last week, McCarter was hospitalized for an incident related to her mental health.

At an early-March online town hall hosted by the People’s Coalition for Manhattan DA Accountability, Bragg was asked about McCarter’s case.

Bragg declined to comment on the case or his office’s decision to prevent McCarter from attending an inpatient mental health care facility out of state. “I can’t comment on an open case,” said Bragg, adding that criminalized survivors are “of significant profound importance to me and the person we brought in to run the trial division.”

For McCarter’s supporters at the town hall, his answer fell flat. “It’s been really disappointing as a community that cares about Tracy and about survivors… to see these promises have not yet come to fruition,” said Sojourner Rivers, an organizer with Survived and Punished NY.

Rivers acknowledges that Bragg has had a bumpy start to his term. In January, the new DA released a memo outlining new prosecution policies for the line prosecutors who handle cases, sparking the ire of law enforcement-aligned media and politicians.

Bragg later apologized for the memo and said he took “full accountability” for it being unclear and legalistic.

“I’m not so naive, Bragg is under a lot of pressure,” said Rivers. Yet, she added, “He chose to take on this role. He chose to say what he said about Tracy.”

On Twitter, supporters of McCarter’s have been echoing Rivers’ sentiments under the hashtag #DropHerCharges.

When he was campaigning, @AlvinBraggNYC claimed that it was unjust to prosecute a victim of domestic violence acting in self defense. Now in office, his actions don’t align with his earlier statement. Stay true to your word @ManhattanDA and #DropHerCharges. #StandWithTracy pic.twitter.com/g9c28Xc1Qb

— Emily Carter (@doubleEcarter) March 1, 2022

Bragg supporter Marissa Hoechsetter helps train New York DAs’ offices on gender-based violence and is a survivor of sexual violence. She served on Bragg’s transition team and now says she is frustrated at the pace of change.

“I want things to happen faster. And, I can only imagine what that feels like to somebody who’s in the position Tracy and her family are in,” said Hoechsetter before Monday’s hearing. “It’s important for the administration not to lose sight of these individual cases.”

Hoechstetter said that while she still supports Bragg, DAs’ offices aren’t incentivized to deal effectively with issues of gender-based and domestic violence. “I have an immense amount of respect for Alvin, and really was proud to endorse him,” said Hoechstetter. “I think there’s the person, Alvin. And then there’s the district attorney’s office.”

The race factor

Robbins believes that racism against her mother, who is Black, at least partly explains how prosecutors have handled her case. “I don’t think that you can talk about a case like this without talking about race. It’s just that obvious sort of factor that will always be at play,” she said.

McCarter’s estranged husband Murray was white. The prosecutor on her case, Sara Sullivan, is white, as are the current and future judges on her case, Melissa Jackson and Diane Kiesel, and until recently so was the district attorney.

“The system is responsive to perfect victims. Perfect victims are white, and straight, and cisgender, and middle class, and they don’t use drugs and they don’t have mental health issues, and they don’t talk back,” said Leigh Goodmark, a law professor and expert on criminalized survivors. “And, that’s who the system likes to help.”

“Black women are disproportionately represented among victims of violence who are arrested,” she added.

Nationally, less than 3% of Black women who kill white men were found to be justified, meaning they likely did not face charges, according to a 2014 analysis of national homicide data by the Urban Institute. That’s compared to 13.5% of white women who killed Black men.

In Texas, where Robbins lives, the reality that Bragg plans to press ahead with her mother’s case weighs heavily against the now-expectant mother.

“I’m four months pregnant, and we just thought this was gonna be over,” said Robbins. “And so, I’m trying to wrestle with the fact that my mom might not be present for me in the way that I imagined.”

Divisions among domestic violence advocates in New York City about what role, if any, police should have in addressing domestic and gender-based violence have been playing out for years against the backdrop of the larger defund the police movement.

At one end: organizations with deep relationships with the New York Police Department and other city law enforcement bodies have argued that the NYPD has an essential role to play in ensuring survivors’ safety.

On the other end, grassroots organizers urged investing some of the NYPD’s $10 billion-plus annual budget into resources like housing and income security for survivors.

Late last month, some of these tensions spilled out into the open at a City Council hearing chaired by Astoria representative Tiffany Cabán, who became a star in the defund movement when she came within just 55 votes of becoming Queens district attorney in 2019.

“What’s clear is that the number of people who experience gender-based, intimate partner and domestic violence dwarfs those who access victim and survivor services.”

— Tiffany Cabán, New York City Council member

At the hearing, Cabán and allies called out ways they contend New York City’s law enforcement-centric approach often acts as a barrier to survivors who seek support but may have reasons to avoid the police — including immigration status, past negative interactions with law enforcement, or a history of incarceration.

“What’s clear is that the number of people who experience gender-based, intimate partner and domestic violence dwarfs those who access victim and survivor services,” said Cabán.

At issue in the hearing was a resolution sponsored by Cabán and Councilmember Mercedes Narcisse (D-Brooklyn) in support of a state bill, sponsored by Sen. Zellnor Myrie (D-Brooklyn) and Assemblymember Demond Meeks (D-Rochester), that would get rid of a requirement that crime victims cooperate with law enforcement in order to access financial compensation.

Currently, to access financial compensation from New York State, crime victims must report the crime to police within a week, with some exceptions, and continue to cooperate with police and the local district attorney’s office. Narcisse and Cabán argued that this prevents many gender-based violence survivors, who may be fearful of working with police, from claiming benefits.

“Unfortunately, this is yet another segment of our criminal justice system where social inequities rears its ugly head,” Narcisse said at the hearing.

Gender-based and domestic violence organizations have been pushing to end the link between law enforcement cooperation and survivor assistance.

“It’s a huge barrier to get resources and to get actual support,” said Theodora Ranelli, an organizer with Project Hajra, a gender-based and domestic violence organization serving the Muslim community in Queens. “Most domestic violence survivors don’t call the police or report their abuse. So that’s leaving out a lot of people that need resources.”

Barriers to Resources for Survivors

Many survivors Ranelli works with don’t call police, she said, because in their experience they’re often unfairly targeted for arrest because of xenophobia, racism and misogyny. Ranelli says some immigrant community members also associate law enforcement in their home countries with dictatorships.

Sanctuary for Families, which had a representative at the hearing and regularly partners with the NYPD, also support efforts to remove the law enforcement cooperation barrier. “You should not have to show police involvement to show that you are a victim of gender-based violence,” said Judy Harris Kluger, executive director of Sanctuary for Families.

Whether or not more police make survivors safer is a separate issue from whether survivors should be required to cooperate with police to access the Victim’s Compensation Fund, she contends.

“I believe they have a role regarding victims’ safety,” Kluger said in an interview after the hearing, speaking of the NYPD. “There are situations where the police need to respond and intervene. Because as far as I’m concerned, victims’ safety is paramount.”

Cabán and many of the organizers in attendance argued that rather than investing in policing, making sure investments are made in resources like housing, child care and transportation would go a long way towards helping survivors, many of whom are financially reliant on their abusers, which is a significant barrier to leaving.

Related coverage: ‘Women are routinely discredited’: How courts fail mothers and children who have survived abuse

“Every dollar that we are putting into police means that’s it’s one dollar that we’re not putting into all of these other areas that we know would directly and immediately serve survivors,” Cabán told The Fuller Project and THE CITY.

An analysis conducted by Janie Williams, an organizer at Survived and Punished NY, a group that works with incarcerated survivors of gender-based and domestic violence, found that the $7.8 million in overtime pay in 2020 for the police precinct with the most overtime in New York City could fund the housing, child care, mental health and transportation needs of 140 survivors for a year.

“The money that we take in investing in these carceral systems of abuse and violence — that’s the NYPD, jails, prisons, we can funnel that money into actually listening to survivors about what they need,” said Williams.

Mandatory Arrests

At the hearing, the Anti-Violence Project, an organization dedicated to helping LGBTQ and HIV-positive survivors of violence, was among groups that pointed out ways people with marginalized identities are often re-victimized once they encounter police.

“Many LGBTQ survivors, especially the ones of color, do not report violence or seek support from law enforcement,” said Alethia Ramos, a member of the Anti-Violence Project, at the hearing. “Because when we do we often face dismissive or negative attitudes or more violence including homophobia and transphobia.”

Cabán also pointed out during the hearing that many LGBTQ+ survivors in New York City end up being the ones arrested when they call for help.

One factor is New York State’s mandatory arrest law, which generally requires police officers to take into custody anyone who commits domestic violence crimes — even if the person who made the call does not want there to be an arrest. Not only can this deter survivors who fear becoming incarcerated themselves from calling police, but it can also scare survivors who rely on their partners financially and cannot afford for them to become incarcerated.

Jared Trujilo, policy counsel with the New York Civil Liberties Union and a former Legal Aid public defender in New York City’s domestic violence courts, says that in practice NYPD officers end up arresting the person being abused along with or instead of the initial aggressor.

“You see many cases when there’s cross-complaints and they’ll arrest everybody,” said Trujilo. “But a lot of times, who they decide to arrest is really just kind of based upon a whim.”

Asked whether policies exist to ensure domestic violence survivors are not arrested when they call police for help, an NYPD spokesperson responded, “Victims of domestic violence are not arrested when they call for assistance.”

Meanwhile, WARM, a domestic violence resource organization whose name stands for We All Really Matter, touted the strength of their relationship with the police.

“One of the things we did during the pandemic was start this partnership with the NYPD when everybody else was running from them,” shared Stephanie McGraw, CEO of WARM and a self-identified Black survivor of domestic violence, at the hearing. “We knew the importance of Black and brown women getting services.”

One point of contention at the hearing was the locations of the city’s Family Justice Centers, run by the Mayor’s Office to End Domestic and Gender-Based Violence. Three of the five borough offices — in Brooklyn, Manhattan and The Bronx — are located in the same buildings as district attorneys.

A 2016 report produced by the City Council recommended that the FJCs rebrand and expand their offices into community-based locations to improve access for survivors who wish to avoid the “criminal legal system” and minimize the impression that working with the criminal system is a requirement to access support services.

“Family Justice Centers are extremely scary and inaccessible,” said Ranelli, of Project Hajara. “It’s right by the courthouse. There’s a lot of police presence. You have to go through a metal detector to get inside, and it’s just not comfortable…. And when somebody needs immediate support, people often need space for healing that is comfortable.”

In her hearing testimony, Commissioner Cecile Noel, a de Blasio appointee who heads the Mayor’s Office to End Gender and Domestic Violence (ENDGBV), acknowledged that problem.

“We absolutely understand that co-location in these spaces can have a chilling effect for survivors,” said Noel. “And we have explored in every way possible ways of making survivors feel more comfortable accessing our services in that space.”

How Will Adams Address this Divide?

For Trujilo, the commissioner’s testimony was welcome. “She was making a lot of points,” he said, “that our side frankly has been making for a very long time.”

Yet Mayor Eric Adams has yet to show signs of taking the office seriously by making his own appointment to the post. Adams touted a public safety plan that does not even mention gender-based or domestic violence.

“What I see from him, he kind of sees the world in this binary way of you are either an abuser or you’re a victim and there’s no gray or nothing in between,” said Trujilo. “He also doesn’t recognize, which is kind of surprising because of his career as a cop…that a lot of the public doesn’t like cops.”

Adams’ office did not respond to a request for comment on the role of law enforcement in domestic violence and his broader domestic violence strategy.

The mayor’s proposed 2023 budget would cut spending for most city agencies, except for the NYPD, the Department of Correction and the Department of Health and Mental Hygiene.

City Council Speaker Adrienne Adams (D-Queens) told The Fuller Project and THE CITY that she intends to keep survivors’ needs in mind as she examines the budget.

“During this budget process and beyond, the Council will examine ways we can continue and enhance City support for all survivors of violence, including domestic and gender-based violence,” wrote Speaker Adams in a statement. “Part of keeping New Yorkers safe is ensuring survivors can access the healing and recovery they deserve.”

Cabán still worries that survivors will be left out in the cold.

“One thing that was really really clear,” Cabán said following the hearing, “was that even before budget cuts we weren’t deeply investing in the things that were going to reduce harm.”

When Marilyn Mendoza took over as the education justice organizer with Make the Road in Jackson Heights three years ago, she noticed that many of the Latina immigrant mothers in her parent group Comité de Padres en Acción craved a safe place to vent.

So Mendoza opened up about her own battle with depression as a child to broach the topic of mental health.

And though at first she received well-intentioned but religious-based comments from some, the women also began to share — about difficulty dealing with not only their children’s anxieties, but their own.

Mendoza quickly put together workshops on self-care and started an art therapy group.

But that was before COVID-19.

Once the pandemic hit, mothers in the group dealt with job loss, remote learning, cramped living spaces, abusive partners and disproportionate deaths of family members.

And due to barriers like immigration status, cost, and lack of interpreters or translation — some Latina women do not speak Spanish as a first language — “they didn’t know where to go or where to seek assistance.”

In November, the Citizens’ Committee for Children released data showing what many clinicians and experts on mental health in the Latino community already knew: Latina mothers in New York City are suffering, and the support provided by the city isn’t cutting it.

Roughly 42% of Latina women with children at home in New York City report symptoms of anxiety or depression, according to the CCC’s analysis of the Census Bureau’s Household Pulse Survey.

“Latina women have always had a higher prevalence of depression in comparison to other women,” said Dr. Rosa Gil, director of Comunilife, a nonprofit focused on mental health and housing services for the Latino community. “I think that challenge has gotten much more critical for Latina women due to the pandemic.”

Issues Compounded

The survey, conducted between April and July of 2021, found that Latina women with children at home were much more likely to report these mental health symptoms than any other group, including Latino men with children at home, 30% of whom also reported symptoms of anxiety and depression during that period. Roughly 36% of both white women and Black women living with children reported symptoms of anxiety and depression.

“We were in the epicenter of the epicenter of the outbreak,” said Mendoza, whose program runs out of Jackson Heights in Queens.

During the height of the pandemic in the spring of 2020, Latinos in New York City were dying at twice the rate of white and Asian New Yorkers, according to data from the Department of Health and Mental Hygiene.

Gill says grief from losing loved ones during the pandemic compounded many of the pre-existing mental health issues among Latina mothers.

Economic factors also played a significant role, said Gill. Latino families with children were more likely than any other racial group to report loss of income, according to the CCC report. Thirty-five percent of Latino families lost income from April to July, compared to 19 percent of non-Hispanic white New Yorkers.

Data from August showed that Latino workers in New York City had significantly higher unemployment rates than white workers. And national data from the UCLA Policy & Politics Initiative found that Latina women suffered the largest drop in employment of any group in the U.S. during the pandemic.

It’s a “perfect storm,” said Mary Adams, director of mental health and wellness at University Settlement, which provides family medical services to those living on the Lower East Side.

“So many of these women were holding their families together,” said Adams. “They were losing jobs and not replacing their income and, in some cases, may not have been eligible for benefits.”

Many benefits, like child care, were already difficult to access before the pandemic.

In November, THE CITY and The Fuller Project found that 55% Latina women with children reported being out of a job well into the city’s pandemic recovery, a number driven largely by child care issues.

Related: Women With Children Having Harder Time Re-entering NYC Workforce

A lack of paperwork makes it hard to access other social supports.

“There are some vouchers that the city and the state provides. But they request a lot of things our families don’t have — one of them being Social Security numbers, pay stubs,” said Mendoza.

And distrust of mandated reporters — professionals like social workers, teachers and doctors, who are required to call in suspected neglect or abuse to the state — can be particularly difficult for Latina women who are undocumented, Mendoza added.

Strength in Numbers

One thing organizations like Masa and Make the Road have found helpful: Creating groups where moms feel comfortable sharing and supporting each other.

Padres en Acción, or “Parents in Action” in English, is one in The Bronx. (A separate but similarly-named counterpart to the Jackson Heights group.)

The group of caretakers — mostly women — was created at Masa, a South Bronx nonprofit focused on serving Mexican and Central American New Yorkers, many of whom are Indigenous and whose first language is neither English nor Spanish.

In March 2020, the group was focused on a campaign against bullying in schools. But that quickly changed when the COVID-19 pandemic slammed into the borough.

For one mother, the turning point was when she began to worry about changes in the mental health of her cooped-up teenage son. So she went to Padres en Acción to talk about it.

There, she found that she and her son weren’t alone in dealing with the fallout of death, job loss, and isolation.

And many of her fellow parents realized that they too wanted help with the pressures of navigating uneven communication from schools, income barriers, language access. Frustration with being unable to help children with remote schooling technology was “a big source of stress,” said Aracelis Lucero, executive director of Masa.

“One of the biggest burdens…especially for immigrant families, and the reason why they migrate here, is a better life and future for their children,” she noted.

The parent-led group issued a set of demands to the District 7 schools superintendent in the South Bronx: Improve communication to immigrant children and their parents about what social-emotional supports were available to the entire family, to create a plan that “is equitable and available to everyone,” and to train all staff to recognize kids who need help.

“We asked that they inform all parents about the help,” said the mother, who requested anonymity because she wasn’t authorized to discuss the group’s issues publicly. “That they have access to that information — because in the Department of Education they said that if you or your child needed help you could ask for it. But our parents didn’t know that!”

As the omicron variant has overwhelmed the city, she wants Mayor Eric Adams to take more decisive action to lower all the barriers to mental health care that her own family and community still disproportionately face.

“He’s always talking about how there won’t be differences [in treatment] between different communities,” something that just hasn’t been true, the mother told THE CITY in Spanish. “Because we’ve realized during this pandemic that there are differences and that equity in reality doesn’t exist.”

Efforts by de Blasio Administration

The administration of former Mayor Bill de Blasio made strides in improving access to mental health services, said Mary Adams. In 2016 the former mayor created NYC Well, a hotline that connects New Yorkers to free mental health services.

Since its inception, the hotline has responded to over a million messages from New Yorkers reaching out for support for themselves or others. By focusing on mental health care, Adams believes de Blasio’s administration helped to destigmatize the issue, which helps people receive the care they need.

“New York City spends more time and energy on mental health than others, and the de Blasio administration did really highlight mental health,” she said. “But there’s still much to be done.”

Masa also reported that it recently began two groups dedicated to undocumented youth and parents’ mental health needs — funded through the city Department of Health and Mental Hygiene.

It’s important to address the differences in the mental health, language and cultural needs within the Latina community, said Dr. Pamela Montano, director of the Latino Bicultural Clinic in the Department of Psychiatry at Gouverneur Hospital in Manhattan.

“We have a very diverse population, and that’s the beauty,” said Montano. “But also, it makes it difficult, right? Because we have so many needs on so many levels.”

Low-literacy community members and those who may speak an indigenous language as their first language can find difficulty in accessing ”something as simple as navigating the phone system ‘dial one for this, two for this,’” even in Spanish, said Lucero.

“It’s really hard for like non-native Spanish speakers to navigate that, even if Spanish is a language that is available on the phone. So in general, those are the people that we’re seeing are really being left behind.”

To bring these parents back to the table, Masa’s Padres en Acción group is asking for city services to be in-person once again.

“Because I know there is help, but it’s only virtual,” said the Bronx mother. “And even if they’re free, one can’t just turn up and ask for an appointment for myself and my family.”

What, If Anything, Can the Adams Administration Do?

Focusing on issues like income inequality and access to affordable housing would go a long way toward helping Latina mothers like those in Mendoza’s group, said Gill.

“The reality is that we have a broken mental health delivery system,” she says. “It has to be community-driven, and it has to be driven by social determinants of health, which are the ability to eat and have food on the table and have a roof over your head.”

“I think he needs to partner with the state to really figure out how we can actually address this behavioral health crisis,” said Jennifer March, executive director of the Citizens’ Committee for Children. “And then embed behavioral health services in place-based settings in early education, schools and communities, that function and that are accessible.”

Lucero stressed that the city’s schools need to step up for the parents in her programs and offer more basic support to parents, like language and computer classes.

The Department of Education pointed out it does offer online classes to help parents assist their children with online learning and provide up-to-date COVID-19 information in multiple languages, including Spanish.

However, Mendoza says that mental health services and basic economic and social supports need to be in person, something the mother from the Padres en Acción group also stressed.

And, said Lucero, the city needs a more permanent solution that makes pandemic direct aid “part of the norm, not the exception” for all New Yorkers — including the undocumented and indigenous communities.

“It’s great we have a hotline where people can call in,” said Mendoza. “But now we needed to take it to another level where we’re funding the services, so that they become long-term services for families, for individuals, and that it’s services that are accessible to everyone and anyone, regardless of status or language.”

Mental Health Resources and Self-Harm Prevention:

- 1-888-692-9355 NYC Well Free Mental Support Health Hotline

- 212-684-3264 National Association of Mental Health (NAMI) NYC Hotline

Families with children in city pre-K and 3K programs are grappling with lengthy quarantines and lack of access to testing following exposure to COVID-19 during the Omicron surge — without the “test-to-stay” program that’s letting K-12 students remain in the classroom with a negative result.

It’s a “crisis moment,” said MC Forelle, 35, a parent of two small children in Windsor Terrace, Brooklyn.

On Tuesday, Forelle learned her 3-year-old son had been exposed to COVID-19 in his classroom.

Under the Department of Education’s stated quarantine requirements, she is required to keep him home from the Bishop Ford pre-K center in Greenwood Heights for 10 days.

Forelle also decided to keep her other child, who’s 5 months old, home from day care as a precaution. That leaves the Cornell Tech researcher back in the position of trying to juggle full-time work from home and child care alongside her partner, like they did earlier in the pandemic.

“I do know that this is going to have some really long term effects for my career,” she said. “I’m not going to have much to show for the last year, not even to speak of the next few weeks. And I know this is going to have a big impact on me long term.”

Forelle’s frustrations largely lie with the DOE’s testing and quarantine program for early education. This week, the DOE began implementing a “test-to-stay” program for K-12 students, which allows children who’ve been exposed to COVID but test negative to return to school after five days.

Under test-to-stay, public school students receive two free take-home antigen tests, which their parents are asked to administer on the day the child receives the test and again on the fifth day after exposure.

But children in early childhood education programs are still required to quarantine for the full 10 days if they’ve been exposed to the virus — even if they test negative. And as of this week, families in DOE early education programs have not been provided with testing kits.

“The fact that the DOE has decided not to send at-home testing kits with Pre-K and 3K families is f–king wild to me,” said Forelle. “These are the only students that the DOE has that are not eligible to be vaccinated, and yet, they’re the only students who are also not eligible to take home at-home tests.”

Attendance at Bishop Ford was 68% on Thursday, the Department of Education’s website shows.

On Friday, state health officials released figures showing nearly 400 New York City children hospitalized with a positive COVID test at some point in the week beginning Dec. 26, many of them because of COVID-related symptoms. Among them, 55% are under the age of 5, and 91% of hospitalized children ages 5 to 11 were unvaccinated, according to the state Department of Health. Children under 5 have not yet been approved by federal authorities for any vaccine against COVID-19.

Meghan Groome, 44, a Park Slope, Brooklyn, resident who also has a 3-year-old enrolled at Bishop Ford, says she doesn’t understand why the “test-to-stay” policy would not extend to children in early education programs whose parents are especially in need of child care.

“As a science person, I’m baffled by that policy,” said Groome, who works at the New York Academy of Sciences, “As a mom, I just broke when I read that policy. Like, why do you hate toddlers and their families?”

The week before her school’s holiday break, Groome’s daughter had an exposure and was required to quarantine. Groome is the only earner in her household, and says that the quarantine requirements greatly impacted her ability to get work done because she had to provide round-the-clock child care all on her own to protect others from exposure.

Now, she worries what will happen if her daughter has to quarantine again for a 10-day period.

“This age group is not eligible for vaccination…and then also not eligible for the things that we know keep them safe and in school, which is the test-to-stay policy,” she said. “It feels like a really pointed policy at the working parents who have small children.”

Tests for the Symptomatic

Children in K-12 programs deemed exposed to the virus at school began to receive tests as of this week, and the DOE says that they will begin delivering testing kits to early education programs starting next week.

However, unlike K-12 students, early education students will receive at-home tests only if they are symptomatic, according to DOE spokesperson Sarah Casasnovas. Early education students who’ve been exposed to COVID-19 but are not currently symptomatic will not receive tests. But in any case, there will be no way to shorten the length of the 10-day home quarantine if they have an exposure.

“Nothing is more important than the health and safety of our school communities,” wrote Casasnovas in a statement to the Fuller Project and THE CITY. “We continue to maintain a hyper-vigilant quarantine policy for all early childhood students to ensure the health and safety of our youngest learners who are not yet eligible for the vaccine.”

Some families have begun organizing efforts for parent associations to pay for expensive private testers to come to their schools to give them peace of mind about their children’s safety and the safety of other children and adults in their household. While this wouldn’t impact the 10-day quarantine requirements, it might allow families more flexibility when it comes to working in person or making child care arrangements.

Relatively privileged families, with the ability to work from home, have tended to be more proactive in reaching out to journalists to bring attention to parents’ plight.

State Senator Jessica Ramos (D-Queens), worries about the possibility that families in wealthier parts of the city could have access to testing resources not available to those in lower-income communities. “All of these things should be easily and readily available to everybody,” said Ramos, who has lobbied for the state to send every household free at-home tests in the mail.

Nicole Sokolowski, 36, in Forest Hills, Queens, made the decision when school resumed after the New Year to keep her 3-year-old home from his 3K program to avoid him picking up the virus.

Her decision proved prescient when a COVID exposure was reported in the classroom while he was home.

“We don’t have really a clear endgame in sight of when we would send him back,” said Sokolowski, who has felt her work take a hit because of having to provide full-time child care alongside her husband even though she works from home.

Access to child care has continued to be a major impediment to mothers attempting to stay or re-enter the workforce in New York City. Census Bureau data analyzed by the nonprofit Citizens’ Committee for Children showed that 41% of 25 to 54-year-old women in New York City with children in New York City were not working at the end of the last school year — when school for most children was fully or partially remote — compared to just 24% of men.

The majority of these women identified lack of access to child care as their primary barrier to participating in the workforce.

Sokolowski says she wishes the city had made more effort to ensure that parents with children in early education programs received tests this week and were given the same testing opportunities as older children. “I would have felt more supported if it was there,” she says.

The pandemic recession recovery isn’t reaching New York City mothers who face steep challenges in breaking back into the workforce — underscoring a growing child care crisis, a new report from a children’s advocacy group found.

The report by the nonprofit Citizens’ Committee for Children, shared with The Fuller Project and THE CITY, found that 41% of 25- to 54-year-old women living with children in the New York metropolitan area were not working between April and July.

That 41% was an improvement over the 50% of women who had reported being out of work at the peak of the pandemic economic shutdowns a year earlier. But male parents’ employment made a much bigger recovery, the report found, with the share of dads out of the workforce dropping from 45% to 24%.

“Women and women of color are really being very hard hit on many levels, like income loss, job loss and being pulled out of the workforce due to child care responsibilities,” said Jennifer March, the group’s executive director. “It seems like their recovery is slow right now.”

The Census numbers showed women who reported being Hispanic/Latino as the likeliest to report not working, at 55%. Among Black non-Hispanic women, 46% reported not working, while that figure was 39% Among Asian non-Hispanic women and 36% among white non-Hispanic women.

Making Child Care Flexible

The Citizens Committee for Children culled the data from the Census Bureau’s Household Pulse Survey, an effort by the Census Bureau to take demographic snapshots of the pandemic’s effect.

The New York City women surveyed between April 23 and July 5 were two and a half times more likely than men in the same age range to list child care as the primary reason for being out of the workforce, according to the analysis.

For Yansy Henriquez of the Bronx, balancing the cost of child care with how much she earns at a local beauty salon has made her question her ability to stay in the workforce.

To afford the nearly $800-a-month price tag of her baby’s day care during the pandemic, Henriquez cut down on internet, cable, her cell phone plan, clothing and even food.

And despite being quickly accepted into affordable child care programs for her older children over a decade ago, she said she has never even received a response from city programs for her 1-year-old daughter.

“Is there not a way to make child care more flexible for low-income moms?” Henriquez, 39, asked in Spanish. “Because I know that all those mothers who have child care, they’re going out looking for jobs and working. But if not, if they don’t have help, they can’t.”

‘People Want to Work’

While news articles abound on the challenges some employers have had in finding workers, child care experts and community organizers in New York City told THE CITY and The Fuller Project there is more to the story — especially for low-income mothers.

“People do want to go to work,” said Mirtha Santana, chief program officer at RiseBoro, a Brooklyn-based nonprofit that offers social services. “But when it becomes [a decision between] either working or having a better child care situation for your child, especially when that job is minimum wage, people make their choices.”

The pandemic temporarily shut down child care centers and job-placement sites where parents could get help signing up for child care, while making other support resources more difficult to access.

Meanwhile, remote and hybrid school were still in place for most public school students during the span of the Census survey, requiring intensive family support for students learning at home.

“I’m surprised it’s not a larger number, to be honest with you,” said Dawn Mastoridis, Child Care Director at Queens Community House, a multi-service settlement house and community resource center, referring to the percentage of New York mothers who were not working at the end of the last school year.

“Women have always historically been the primary caregivers who had to stay at home with children, and the process to get child care coverage is not an easy one,” said Mastoridis, who has helped shepherd parents through applying for subsidized child care.

In addition to dealing with long wait times for resources like child care vouchers, the amount of paperwork required to apply for that help can be a huge barrier for parents, advocates say.

This is especially true for parents with non-traditional jobs offering little or no documentation of employment, or for parents dealing with language barriers, said Mastoridis.

“It’s a challenge,” she added. “You have to have a lot of stamina and perseverance, and I could see why parents might give up on the process.”

Bleeding Money to Stay Working

For mothers who can’t access city-run child care programs, paying out-of-pocket can be untenable in the long term.

Jaime-Jin Lewis, Founder and CEO of WiggleRoom, a tech firm that aims to increase access to child care, said some parents will bleed money simply to stay in the workforce.

“I worked with multiple women who paid more for child care than they took home just because they wanted to have a job,” said Lewis. “They thought that they would have more opportunities in the future even though they were quite literally losing money to go to work.”

Tahvia Walter, a 29-year-old mother of two from Brownsville, Brooklyn, has been waiting for the right job to jump back into work. Low wage jobs just won’t cut it anymore, she said.

When she first lost her last minimum-wage job in May, Walter said, she felt a “sigh of relief.”

She was able to help her 8-year-old daughter do better in remote schooling. Walter also didn’t have to worry about bringing COVID-19 back home to her family — or about whether she would be allowed to take time off to care for a sick or quarantining kid.

She wishes that the city would do more to help mothers like her find positions “that are worth your while” — with benefits, flexibility around family life and a liveable wage.

Walter said she has turned down positions that didn’t offer work-family balance.

“They [the employers] put it in plain terms: ‘We come before anything,’ and I will fight because nothing comes before my children,” she said.

Federal, State Help on Horizon

Some see hope in the paid family leave and child care provisions in the Biden administration’s $1.75 trillion Build Back Better bill.

The bill, which passed the House on Friday morning, earmarks $400 billion in child care spending on universal preschool for 3- and 4-year-olds.

Although the federal package would be a big step, State Sen. Jabari Brisport (D-Brooklyn), who chairs the chamber’s Committee on Children and Families, said more needs to be done to ensure all mothers can access child care.

“It’s always good to have more money invested into the child care sector. I will say it’s definitely not as aggressive as it could be,” said Brisport, who said he’s committed to passing universal child care — with no income requirement — at the state level.

Gov. Kathy Hochul echoed Brisport’s commitment to expanding access to child care during an online child care listening tour event hosted by the Brooklyn Democrat last Wednesday.

“As I’m preparing my first budget, child care is a major priority,” said Hochul over Zoom. “I plan to work with [Brisport] to craft a strategy that is going to be transformative to address the needs of these families and the challenges of providers.”

At the city level, Mayor-elect Eric Adams has pledged to expand access to child care.

“Child care is a moral imperative, period,” Adams tweeted during his primary campaign while highlighting his plan to provide child care for “all who need it.”

For her part, Walter finally “took that leap” and accepted a new government job she believes will allow her to balance family and work. She is due to start in January.

“Going to work feels like you’re potentially sacrificing your health, the health of your kids,” she said. “So making a sacrifice like that to make minimum wage and pennies is not something that I think a lot of people are willing to do.”

Child care providers in buildings managed by the city’s public housing authority say despite years of fighting for better conditions, youngsters face unsanitary and at times unsafe conditions.

And the providers, grappling with massive economic blows due to the pandemic, contend New York City Housing Authority has often left them to pick up the tab for necessary repairs.

Dawn Heyward, deputy director of early childhood education at East Side House Settlement, whose program runs out of a Bronx NYCHA facility, said she’s been waiting five years for Housing Authority officials to provide air conditioning and heat to the center’s gymnasium.

Her center had to pay out of pocket to ensure consistent heating in classrooms by installing its own dual air conditioning and heating units, Heyward said.

“NYCHA is the most challenging part of my job,” she added. “Not the child care, but making sure when the children walk in this building they’re safe.”

Child care centers typically lack funds to pay for things like heating equipment, said Heyward, whose program is federally funded.

Issues like lack of heat and hot water, mold, leaks and pest problems go beyond the child care centers in NYCHA facilities. Reporting from THE CITY has found widespread issues with lead and mold in New York City public housing units, in addition to poor ventilation that may have helped fuel the spread of COVID-19 in public housing.

But some providers in the roughly 400 child care centers in NYCHA complexes say the city should pay special attention to the health risks posed to young children.

Hot Water Harm

“School should be a place where you’re safe…and where health and safety should be a priority,” said Yvette Ho, education director at the Jacob Riis Early Childhood Center in the East Village. “But that’s not necessarily the case because we’re working with NYCHA as our landlord.”

Ho said she’s seen clear examples of NYCHA mismanagement, including repeated failures to notify the child care center when leaks are scheduled to be fixed in the residential part of their building. This has led to random hot water shut-offs, resulting in the emergency closure of the center and parents having to take time off from work.

Every year when the building switches on the heat, Ho said, the steam pipes burst without warning, sending potentially scalding water raining down into the center.

Last year, she said, the fire alarm system detected the rising pipe temperatures, allowing the center to avoid any injuries to children. But as winter approaches, she worries that children at the center, who are as young as 1, could be badly burned.

“We’re putting Band-Aids over issues that could have been constantly maintained so that it doesn’t lead up to that — a steam pipe burst,” Ho said.

Massive Repairs Needed

Fixing the problems at Jacob Riis and other facilities is likely to be expensive. In 2019, over $130 million in repairs were needed in day care centers in NYCHA buildings, Chalkbeat reported.

“It’s no secret that there are capital issues at NYCHA,” said Nora Moran, director of policy and advocacy at the United Neighborhood Houses, a nonprofit that advocates for settlement houses throughout the city, including several with child care facilities.

Moran said investments in public housing from the federal government, in the form of infrastructure legislation like the Build Back Better bill, are needed to alleviate NYCHA’s massive repair backlog.

“When NYCHA is suffering, it has ripple effects to a variety of things in the community,” state Sen. Jabari Brisport (D-Brooklyn), who chairs the Senate’s Committee on Children and Families and has been touring child care facilities throughout the state, told The Fuller Project and THE CITY.

Conditions like lack of heat at the East Side House Settlement and broken light fixtures in other facilities Brisport visited indicate inadequate NYCHA funding, he said.

Brisport believes the best way to ensure issues in NYCHA-managed day care centers are safe for young children and staff is to focus on federal legislative efforts. However, if the federal funding falls through, he says New York will have to make up a massive funding gap, estimated at $40 billion, elsewhere.

A NYCHA spokesperson said staff conducts routine inspections of child care centers in NYCHA buildings, dispatches heating plant technicians and property management staff when repairs are necessary and communicates with resident leadership about planned outages.

NYCHA also said it has records of steam pipe leaks in 2018 and 2019 at the Jacob Riis child care center, that the steam pipes there have been repaired and replaced, and that it has added insulation around the pipes to mitigate future leaks. At the East Side House Settlement Mott Haven location, NYCHA says it is currently working with an outside HVAC contractor to address the issues with heating and air conditioning reported by Heyward.

‘A Systemic Problem’

Democratic mayoral nominee Eric Adams has said that if elected he would ask for tens of billions in federal funding to repair NYCHA facilities. In addition, Adams said he would create a monitoring program called “NYCHAstat,” to track spending and repairs status, according to Gotham Gazette.

Adams has not called for additional New York City funding for NYCHA, according to the Association for Neighborhood Housing Development.

At Jacob Riis, Ho says response time to maintenance calls has improved thanks to her team’s efforts over the years to build up relationships with local management. Still, much work remains to safeguard the children attending day care in NYCHA facilities.

“This is like a much bigger problem than one child care facility in one development in New York that they can fix like that,” Ho said. “This is a systemic problem.”

What’s next for former New York City mayoral candidate and civil rights lawyer Maya Wiley? She says she isn’t going to run for governor. But she still wants to see her plan to provide universal community care for children and older adults realized.

“There is no reason why our child care plan can’t become reality,” said Wiley, who came in third in the June Democratic mayoral primary won by Brooklyn Borough President Eric Adams. “It’s just a matter of political will.”

During the campaign, Wiley put forth an ambitious child and elder care platform, which would have given $5,000 to 100,000 “high need” families in New York City to help with the costs of providing care to children, older adults and other family members. Wiley’s plan, developed in deep consultation with community activists and other stakeholders, would have also created community care centers in every borough.

“Even before COVID … families, and particularly women, were overwhelmingly bearing the burden of trying to figure out quality childcare in order to be able to work,” Wiley told THE CITY and The Fuller Project. “It’s not just about whether there is a [care] subsidy, which we need, but that there’s a place where people can go and that place is also in [the] community.”

In 2019, a city comptroller report found that half of New York’s community districts were infant care deserts. In 10 neighborhoods, including Bushwick in Brooklyn and Sunnyside in Queens, there were more than 10 times as many infants as child care slots.

Wiley says she has spoken to Adams since the election, but that they’ve yet to discuss her child care platform, which would have drawn money from the NYPD’s budget, among other sources.

Adams, a former cop who has spoken out against the “defund the police” movement seeking to redistribute police department funding to social programs, has suggested he is open to using federal stimulus funds to increase the NYPD’s budget.

“We should utilize the money to stabilize crime in the city,” Adams said at a news conference after his primary victory, according to the New York Post.

“That’s an area where Eric and I differ,” said Wiley, whose plan would have shifted $300 million from the NYPD and Department of Corrections budgets by reducing future hiring of police officers and corrections officers. That would have decreased the number of NYPD officers by 2,500 over two years.

‘Historic inflection point’

Adams has pledged universal child care — proposing tax breaks to building owners who provide free child care space, expanding a tax credit for low-income families, and opening community-based health and care centers in low-income neighborhoods.

Other candidates including runner-up Kathryn Garcia, who pledged to make child care free for parents with children 3 and under making less than $70,000 a year, and New York City Comptroller Scott Stringer also promised investments in child care. Stringer’s plan would have invested $500 million in five years to tackle child care deserts and expanded access to the city’s child care voucher program for children 3 and under.

Adams is unlikely to divert the kind of money Wiley proposed shifting from policing into community-based care.

But All our Kin, a nonprofit focused on family child care providers, says the money already in the city’s budget and the federal child care block grants would give an Adams administration an “enormous” opportunity to improve New York’s care systems.

“We’re looking at a historic inflection point for child care in New York City,” said Jessica Sager, All our Kin’s co-founder and CEO. “Eric Adams has said it is a moral imperative for us to provide universal child care. And we’re so excited about that.”

Adams’ campaign declined to comment for this story.

Wiley says she took a break after an “exhausting” campaign. However, after the general election in November, the former MSNBC contributor expects to help push for the ideas in her care proposal. “The child care proposal I put forward as a candidate for mayor was not just the Maya Wiley proposal,” Wiley said. “It really was about a plan and a vision for the future of the city and for our people.”

Last year, as the realities of the pandemic set in, Veronica Leal’s house-cleaning clients stopped calling and her household funds dissipated.

Leal made a grocery run to buy food in bulk, hoping to make it last by eating one meal a day. She told her teenage daughter to study hard and become a professional — like the people whose homes Leal cleaned, who were better able to weather the pandemic’s economic fallout.

Leal came to the United States at 16 from Mexico. Now 35, she lives in Washington Heights. As the lockdownwore on, Leal watched fellow immigrants in her Manhattan neighborhood grapple with the same reality: Despite their hard labor, they were not considered deserving of the economic security that their adopted country advertised.

“I love to work. I love to contribute to this country,” Leal, who had spent 12 hours a day working to support herself and her daughter, said through an interpreter.

Immigrant women, including those from working-class backgrounds, have faced particular hardship during the pandemic. According to the Migration Policy Institute, they entered the pandemic with unemployment rates roughly similar to the rest of the United States, but saw a steep mid-year escalation in joblessness that peaked in May 2020: At 18.5%, their unemployment rate far exceeded the 13.5% rate among their U.S.-born women at the time.

Immigrant women’s unemployment remained higher than that of American-born men or women throughout the pandemic, falling below the other groups only in July 2021. But in August, job losses among immigrant women spiked again, likely due to the spread of the Delta variant, said Julia Gelatt, MPI’s senior policy analyst.

In New York City, the pandemic compounded existing economic insecurity across racial and gender lines. Grocery clerks, hospital staff, street vendors, domestic workers, nail technicians, cleaners and caregivers could not do their jobs remotely. So they either risked their health on the frontlines as essential workers — if they even had employment opportunities — or watched their sources of income dry up.

Many, especially undocumented New Yorkers, were excluded from the early rounds of federal stimulus aid. Anxieties about missing rent and bill payments bloomed.

In the absence of comprehensive government safety nets to deliver them from economic distress, immigrant women like Leal banded together, adapted their skill sets and organized aid.