Editor’s Note: Since this article’s publication, the UK’s Joint Committee on Vaccination and Immunisation issued new guidance, that pregnant women be offered the COVID-19 vaccine at the same time as the rest of the population, based on their age and clinical risk group.

In December, when the United Kingdom first rolled out its vaccination program and prioritized frontline health workers, Zara* and her colleagues jumped at the chance to get vaccinated. The country was in the grips of an intense second wave of the coronavirus outbreak and hundreds of people, including health workers, were dying every day.

But unlike her colleagues, Zara, a doctor in the Midlands area of England who was in her first trimester of pregnancy, was not offered the vaccine, she says. When she inquired whether or not she could get the vaccine ― at the hospital where she works and at her doctor’s office ― Zara says she was turned away. She requested anonymity for this article, citing concerns she could be penalized by her employer for speaking out.

Zara continued to see patients daily, despite emerging evidence that pregnant people are at higher risk of severe COVID-19, especially women of color like herself. In March of this year, she tested positive for the virus and developed a heavy cough and fever at six months pregnant. Her partner, who has an underlying condition, also developed a fever after catching the virus from her.

As a frontline worker, Zara has been eligible for a vaccine under U.K. government guidance since the end of last year. Yet evolving and ambiguous guidelines ― which say that pregnant women can “discuss” vaccination with their doctor if they are at high risk of exposure ― and the fact that the rules changed, having initially said pregnant women shouldn’t be vaccinated, means she has faced repeated obstacles.

“Thankfully I’ve recovered [from COVID],” Zara says, as has her partner. “But the ‘what ifs’ are there. And I worry about other women, and those around them.”

The original clinical trials for all the COVID-19 vaccines currently in widespread use excluded pregnant and breastfeeding people. As a result, most countries and health bodies are taking a cautious approach, issuing guidance that doesn’t prioritize pregnant people for vaccinations but doesn’t completely bar them, either. But in countries around the world, the confusion is creating vaccine hesitancy among pregnant patients and the doctors responsible for their care, meaning many women aren’t being vaccinated even when they’re high risk.

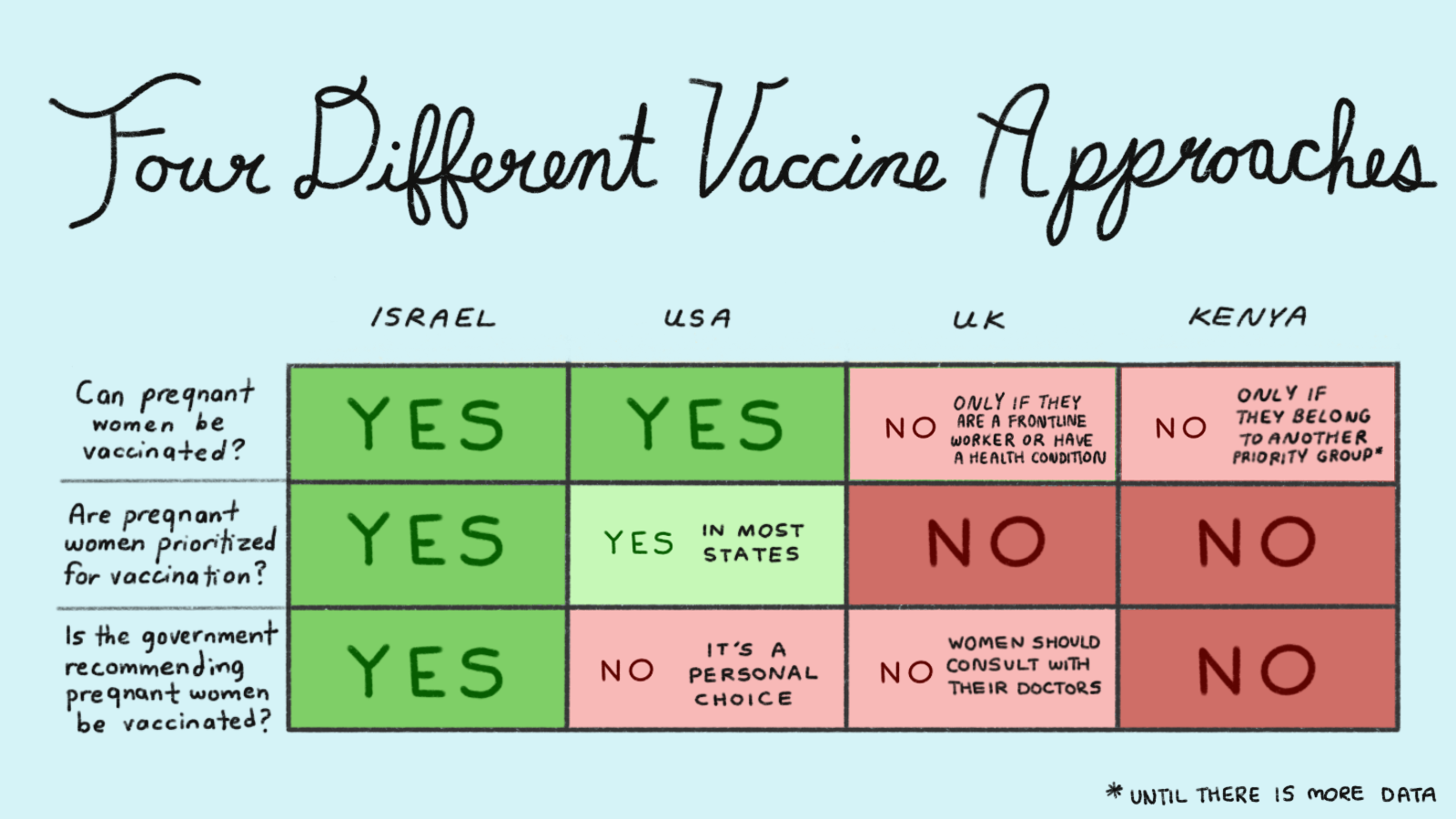

Amid a lack of conclusive, available data, countries, and even regions within countries, are taking drastically different approaches to vaccinating pregnant and lactating people.

Israel, for example, is actively encouraging and prioritizing pregnant people to get vaccinated, while most U.S. states and some parts of Canada are designating pregnancy as an underlying condition and prioritizing pregnant people for vaccination.

The United States Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) says it is a “personal choice,” but notes that pregnancy is a risk factor for severe COVID-19 and that, “based on how these vaccines work in the body, experts believe they are unlikely to pose a specific risk for people who are pregnant.” Meanwhile, vaccine manufacturers, citing lack of data, say it’s up to health regulators to make recommendations as to whether or not pregnant people should get vaccinated against COVID-19.

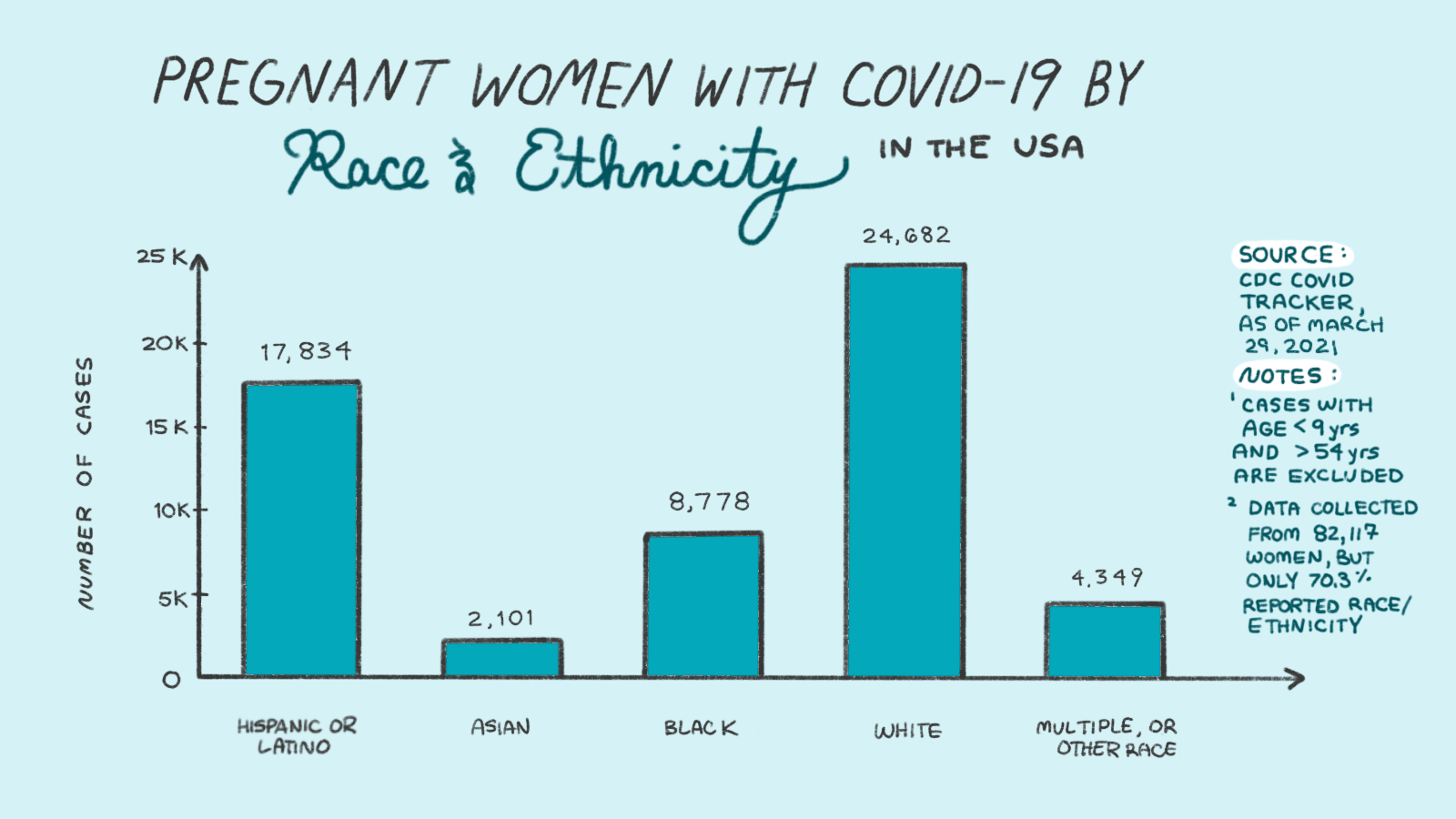

Ghana, the United Arab Emirates and some parts of Nigeria are barring pregnant people from receiving the vaccines entirely, for now, saying there is not enough evidence on their safety. Many other countries lack clear policy (or have yet to roll out vaccines, due to short supply). That is despite evidence that pregnant people, particularly people of color, are more at risk of severe COVID-19, as well as preterm labor. A major study published by the CDC in November found that while overall risks remained low, the chance of intensive care unit (ICU) admission, invasive ventilation and death was higher among pregnant women with symptomatic COVID-19.

The limited research so far around vaccinating pregnant people against COVID-19 is promising: MRNA vaccines protect both pregnant and lactating mothers and their newborns, according to a study published in the American Journal of Obstetrics and Gynecology in late March. The Pfizer and Moderna vaccines produced just as strong an immune response in pregnant people as non-pregnant people, said researchers at Massachusetts General Hospital, Brigham and Women’s Hospital and the Ragon Institute of MGH, MIT and Harvard. They also found evidence of antibody transfer between mothers and their babies, through the placenta or breast milk ― suggesting an additional benefit that vaccinating mothers could also help protect their babies.

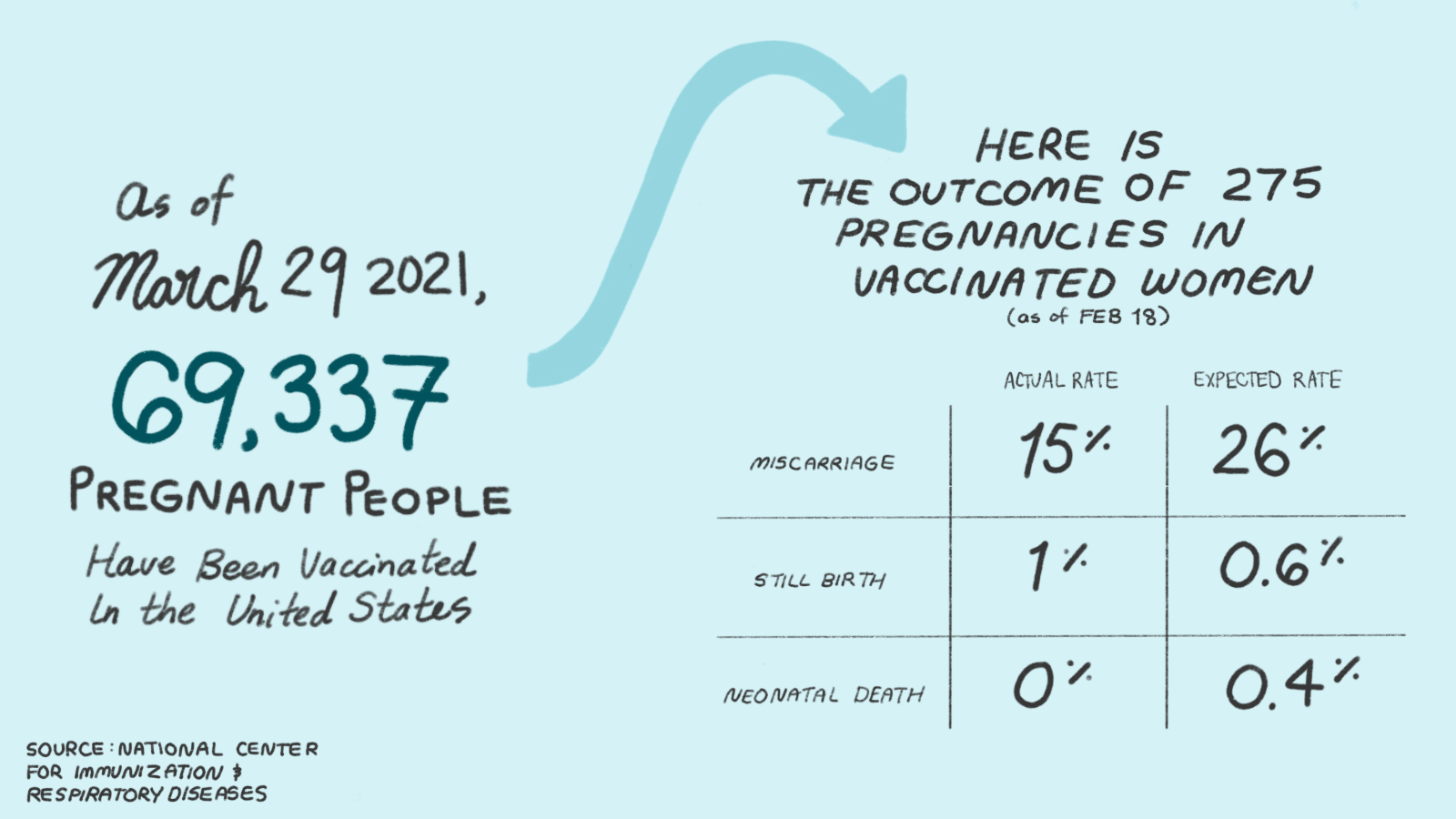

In February, Pfizer began a clinical trial involving pregnant people, although it won’t conclude until January 2023. The U.S. government is tracking more than 4,000 people who received the Pfizer and Moderna mRNA vaccines at various stages of pregnancy. In its latest update from mid-February, when there had been 275 completed pregnancies among this group, the CDC said there had been no “unexpected” outcomes, with miscarriage rates and complications within normal ranges.

In Kenya, pregnant and lactating people are not being prioritized or encouraged to get the vaccine “as a precaution,” says Dr. Willis Akhwale, chair of Kenya’s COVID-19 vaccination taskforce. Kenya, which received just over a million doses of the AstraZeneca vaccine in March via the COVID-19 Vaccines Global Access facility, or COVAX, is prioritizing health workers, teachers, security personnel, clergy and people over age 58 in its current vaccine rollout. Meanwhile, people like Wangeci Njuguna, who is eight months pregnant, have been told they are “not eligible” for the vaccine. Health workers at Mathari National Teaching and Referral Hospital, one of Nairobi’s designated hospitals offering the vaccine, recently turned Njuguna away because pregnant women are not on the priority list.

“I wanted to get the vaccine because the third wave of the virus has killed a lot of people,” said Njuguna. “I wished to ensure I was protected and so was my child. Hospitals are full, there’s no oxygen in some facilities and yet we are told we can’t be vaccinated.”

Japan says pregnant people should be vaccinated but ideally not during the first trimester. The World Health Organization suggests pregnant women “may receive the vaccine if the benefit…outweighs the potential vaccine risks,” namely, if people are at high risk of exposure to coronavirus or have another underlying condition. The U.K., Australia and many EU countries have issued similar guidance. Germany is taking a slightly different approach: It is only offering the vaccine to high-risk pregnant women “in individual cases” and is instead prioritizing vaccinations for “close contacts” of pregnant people.

It’s “maddening,” says Dr. Jacqueline Parchem, a maternal-fetal medicine specialist working with high-risk patients at the University of Texas Health Science Center at Houston, referring to cases where women have been prevented from receiving a vaccine. We won’t know “until later how many people had bad outcomes [from COVID]…who could have gotten vaccinated but didn’t because of these rules,” she said.

“And probably it’s not being counted, unfortunately.”

Dr. Parchem was herself one of the first pregnant people to receive a COVID-19 vaccine, at the beginning of the U.S. vaccination rollout. “It comes down to a fundamental [question of] ‘do we [as pregnant people] have autonomy or not? Can we make decisions for ourselves or not?’” she added.

Many people say they feel left behind, and are being asked to make the call to get vaccinated or not without the provision of adequate data. The question is becoming more fraught as vaccination campaigns start to move beyond the high-risk categories initially prioritized. Governments are now having to decide whether pregnant women will be included or left out.

In one instance in Israel, a pregnant woman and her 30-week fetus died in February after she decided not to get vaccinated. Despite Israel’s prioritization of pregnant women, she had worried the vaccine might be unsafe due to her pregnancy. At the time, there were 27 other unvaccinated pregnant women in serious and critical condition in Israel due to COVID-19, reported The Times of Israel.

A little over half of pregnant women would get vaccinated against COVID, if they had the choice, according to a survey by researchers at the Harvard T.H. Chan School of Public Health, in which 18,000 women were surveyed across 16 countries between October and November 2020. But pregnant women were far less willing to have the vaccine than non-pregnant women.

Many doctors do believe the vaccines are safe for pregnant women. But in the absence of hard data, they say it is difficult to make a blanket recommendation. The memory of the thalidomide scandal of the 1960s ― in which thousands of babies across nearly 50 countries died within months of being born and others lived with developmental problems due to pregnant women taking the anti-morning sickness drug ― still looms large.

The lack of clear guidance is what led Alyson Shontell, co-editor-in-chief of Business Insider, to take to Twitter in search of answers. Her doctor in New Jersey talked her through the available evidence and guidance from different authorities, she says, but stopped short of giving her a recommendation either way.

“Is there a good resource to help pregnant women weigh the pros and cons of getting a covid vaccine?” she tweeted in mid-March. “My doctor refused to give me any advice saying he ‘didn’t want to be on the wrong side of history.’”

Even as a journalist accustomed to researching complex issues, Shontell told The Fuller Project the available information seemed unclear and that, while her family was encouraging her to get the vaccine, her doctor’s hesitancy made her pause.

“As a pregnant person, you know, it is frustrating to feel like you’re making such a monumental decision kind of alone,” Shontell says. In the end, she decided to get vaccinated at 30 weeks pregnant. She believes she was the first of her doctor’s pregnant patients to be vaccinated. “It was a little bit weird to feel like a guinea pig,” she says.

Even where pregnant and lactating people are eligible, there have been reports of vaccinators turning people away or advising them to “pump and dump” after vaccination, which experts say is not necessary.

The information vacuum has allowed misinformation to spread, at a time when people are relying on the internet and messaging apps like WhatsApp. One unfounded rumor claims that the vaccines could cause infertility; another is that they cause miscarriage. There is no evidence to support either claim.

“There has been a massive problem with rumors about the vaccine, even amongst healthcare professionals,” Zara says. She understands that the lack of data makes people nervous because “the last thing anyone would want is to be responsible for giving something that there’s even a tiny chance could be harmful.”

But in the bid to protect pregnant women and their fetuses by excluding them from clinical trials, and subsequently withholding vaccines or providing unclear guidance, Zara says pregnant women like herself have ultimately been exposed to further risk.

“There are women out there who are pregnant and exposed,” she says. “They know we’re at risk…and there’s a vaccine that could stop some of us getting [sick] or worse.”

***

Jessica Abrahams reported from the U.K. Nasibo Kabale, a reporter at the Daily Nation in Kenya, contributed reporting from Kenya.

*Zara (not her real name) requested anonymity for this article, citing concerns she could be penalized by her employer for speaking out.

Jessica Abrahams

Jessica Abrahams