SÃO PAULO — “I feel like I’m going to die.”

It was just after midnight on April 16, and Vanessa Pereira was chatting with one of her best friends, Jaci Diniz, on WhatsApp. Three days earlier, a doctor had told the 27-year-old psychology student that her exhaustion and shortness of breath were symptoms of COVID-19.

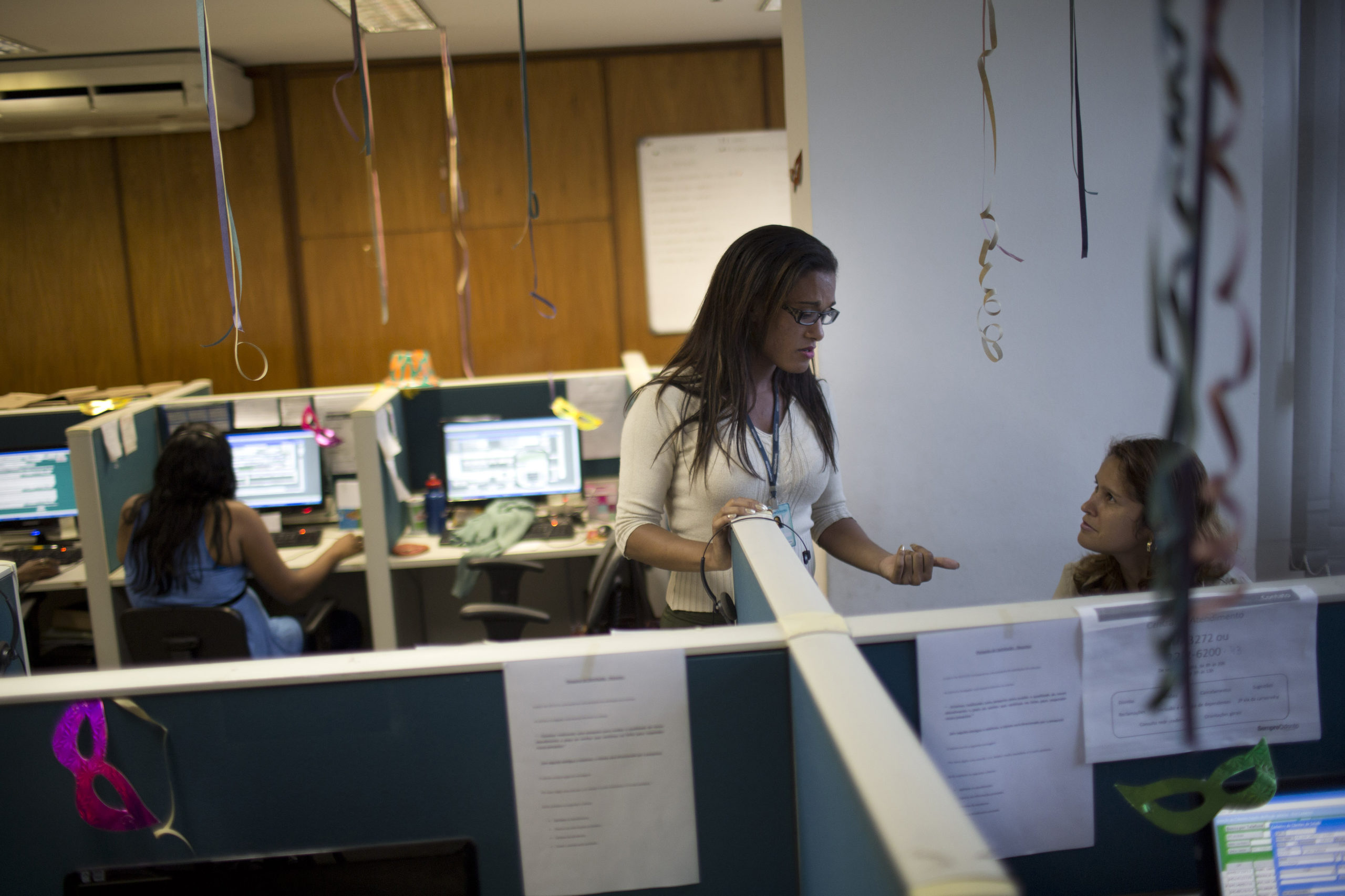

She was tested and sent home with a note to bring to her bosses at the call center where she worked in the northern São Paulo neighborhood of Santana. She was employed by Atento, a telemarketing company that operates in Latin America and is owned by Boston-based private investment firm Bain Capital, which is in talks to sell its equity stake in the company. Atento is present in 13 countries, but the majority of its work is done in Brazil, where it employs some 70,000 people and has 33 of its 48 call centers.

Pereira started working there in 2013, first as an operator and later training new staff in a position known internally as a multiplier. Her commute was long—two hours each way by subway and bus—and when the coronavirus pandemic first hit Brazil, she was still working six days a week. Her heart murmur—a condition, according to a representative from a public-relations firm hired by Atento, Pereira didn’t tell them about—put her at a high risk of infection, as did obesity, a condition impossible to hide.

The company had allowed some of her colleagues to work from home because of pregnancy, old age, and other medical conditions, but Pereira’s husband said she continued to work at the five-story building at least two times a week through the beginning of April.

According to Atento, Pereira was slated to work from home after completing her shift at the office on April 8. But that same day, she sent a former colleague a work schedule showing her shifts through the end of April, which Pereira said she was being made to work from the office.

The day before she was set to return for her scheduled shift on the 14th, she found out she might be infected. “I’m afraid,” she wrote to Diniz, who also used to work for Atento. “Really. I’ve never felt so weak. If something happens, I won’t be able to tell you. I love you.”

Eleven days later, she was gone.

High-stress and poor working conditions

More than 70 percent of Brazil’s call center employees are women. Many are single mothers or women who have been out of the job market in order to take care of children and other tasks related to the family and home. The jobs they take on are high-stress, and the working conditions are often poor. It’s not uncommon for these women to work six hours a day for six or seven days a week in extremely tight quarters, with cameras monitoring their every move, limited bathroom breaks, and salaries that rarely break Brazil’s minimum wage of roughly $200 a month.

Now that the coronavirus has swept Brazil—ranked second behind only the United States in both confirmed cases and deaths, with July 16 tallies at 2,012,151 and 76,688, respectively—these women face extreme risk as they weigh the consequences of staying in a job that could endanger their lives or walking away from the salary they need to keep their families afloat.

According to the São Paulo Union of Telemarketing, Direct Marketing, and Related Companies (Sintelmark), Brazil’s call center industry brought in 43.4 billion reais (currently $8.1 billion) in revenue in 2014; if it were a city, it would have had the sixth-highest gross domestic product among Brazilian municipalities at the time. Hiring in the previous 10 years increased 244 percent, leading to 1.6 million direct jobs and putting 12 billion reais ($2.25 billion) into circulation. The union has also noted that income earned by call center workers is, on average, equal to 70 percent increase in their families’ total income.

Call centers are notorious for having their employees work in close quarters—sometimes at four to a desk and thousands per floor—in offices with closed doors and windows that don’t open. They spend their shifts trying to speak above the din of ringing phones and colleagues’ conversations, creating the perfect storm for the spread of the coronavirus, which is easily transmitted through spittle, especially in enclosed and highly populated spaces.

On March 20, an updated national decree was issued adding work done at call centers to the list of the country’s essential services, defined by Brazil’s federal government as services and activities that, if not carried out, “endanger the survival, health or safety of the population.”

Atento employees swiftly filed a complaint with the Telecommunication Companies Workers’ Union (SINTETEL). According to the employees, no preventative measures had been taken by the company to protect them from the spread of the coronavirus. They said they continued to work at full capacity, without masks, hand sanitizer, or any information about how to keep themselves safe during the pandemic.

“When they declared call centers an essential service I was really scared.”

Pereira worked with the bank Cetelem, one of Atento’s more than 400 clients on a list that includes U.S.-based companies Whirlpool, Motorola, and Riot Games, which announced its partnership with the call center company in May. Brazil’s call center industry started to go global around 2005, when companies from the United States and other developed countries saw an opportunity to lower wages and increase profits. While the shift meant bigger business for Brazil’s managerial class, much of the predominantly female workforce remained mired in poverty.

“When they declared call centers an essential service I was really scared,” said one 19-year-old woman who works as a phone operator at Atento and asked that her name not be revealed, for fear of losing her job. She lives with her sister, who has a heart condition, and three young nephews, one of whom suffers from asthma. She said her $200 monthly salary supports her entire household.

The representative hired by Atento said the company is operating in compliance with the federal decree and now has its call centers working at half capacity, with 30,000 of its employees either sent home because they are at high risk of infection or working from home. The company also said it started implementing “rigorous preventative measures” in mid-March, and began taking employees’ temperatures on April 13 and handing out masks on April 29. In June, the representative said, it installed 1,800 acrylic dividers in its break rooms.

According to vice president of SINTETEL Mauro Cava de Britto, Atento, like other telemarketing companies the union has been pushing to better protect employees from possible infection, hasn’t been transparent in responding to requests for information about how the company is addressing employee health and safety.

Employees at Almaviva do Brasil, another company that operates call centers across the country, went on strike at the end of March, protesting outside one of its locations in downtown São Paulo.

One woman who was laid off from Almaviva do Brasil’s office in Itu because of the pandemic, and who did not want to be identified because she is hoping to get her job back, said that health inspectors visited the company that same month after receiving complaints there was no soap or hand sanitizer in the building. The next day, the products were made available, but the woman said they were watered down so they would last longer.

Another former employee, an 18-year old woman who quit working for the company in April because she feared for her health, but who did not wish to be identified for fear of being blackballed from telemarketing jobs, confirmed the lack of supplies and added that, although Almaviva do Brasil started implementing social distancing measures and stopped scheduling shifts on Sundays, those measures didn’t extend to Saturdays. “At lunch, it was really crowded and all the chairs were still one next to the other,” she said. “Nobody wore masks yet because they weren’t mandatory and all the doors were closed.” She said one attempt was made to have employees work from home, but they were called back into the office after the equipment they took home didn’t work.

Almaviva do Brasil declined requests for an interview, but said in a statement that it has “spared no steps to guarantee the safety of its employees during this moment of the COVID-19-related pandemic and rigorously follows the guidelines of the Brazilian Teleservices Association (ABT), the Ministry of Health and the World Health Organization (WHO).”

She wouldn’t be coming back to work

Pereira’s COVID-19 test came back positive on April 26. The next day, after spending one week at a field hospital, she died.

Many of her friends and colleagues found out about her death on social media. Some only came to know what happened days later, when their bosses at Atento told them she wouldn’t be coming back to work.

But the rest of the employees would.

Pereira hadn’t been to the office since April 8, and Atento didn’t think it was necessary to send the others home. The government had deemed call centers essential. Nothing could stop their work. Not even death.

Jill Langlois

Jill Langlois