Miriam Viegas’s workload has tripled since the pandemic started.

A doctor with the Special Secretariat for Indigenous Health (SESAI), she visits 10 Guarani Mbya villages around the São Paulo town of Miracatu every week, along with two nurses, two technicians, a dentist, and a dental assistant.

Prior to the pandemic, they mostly attended to kids with respiratory infections or adults with diabetes and hypertension, visiting two villages each day of the week. But with the arrival of the coronavirus last year, the demand for medical assistance increased, and Viegas and her team found themselves with one more village to visit. They had to split up into smaller groups so they could get to everybody who needed them as quickly as possible.

“Sometimes it’s the day to visit a certain village, but I hear that someone from a different village is sick, so I have to go there instead,” she says.

An epicenter of the pandemic, Brazil so far has seen 15.4 million cases and more than 428,000 deaths caused by COVID-19, the second most in the world. It’s struggling to vaccinate its population of 211 million and its president, Jair Bolsonaro, is being investigated in a parliamentary inquiry for his mishandling of the pandemic as he continues to attend large gatherings without wearing a mask. The country has also seen shortages of essential healthcare resources, like oxygen and intubation kits.

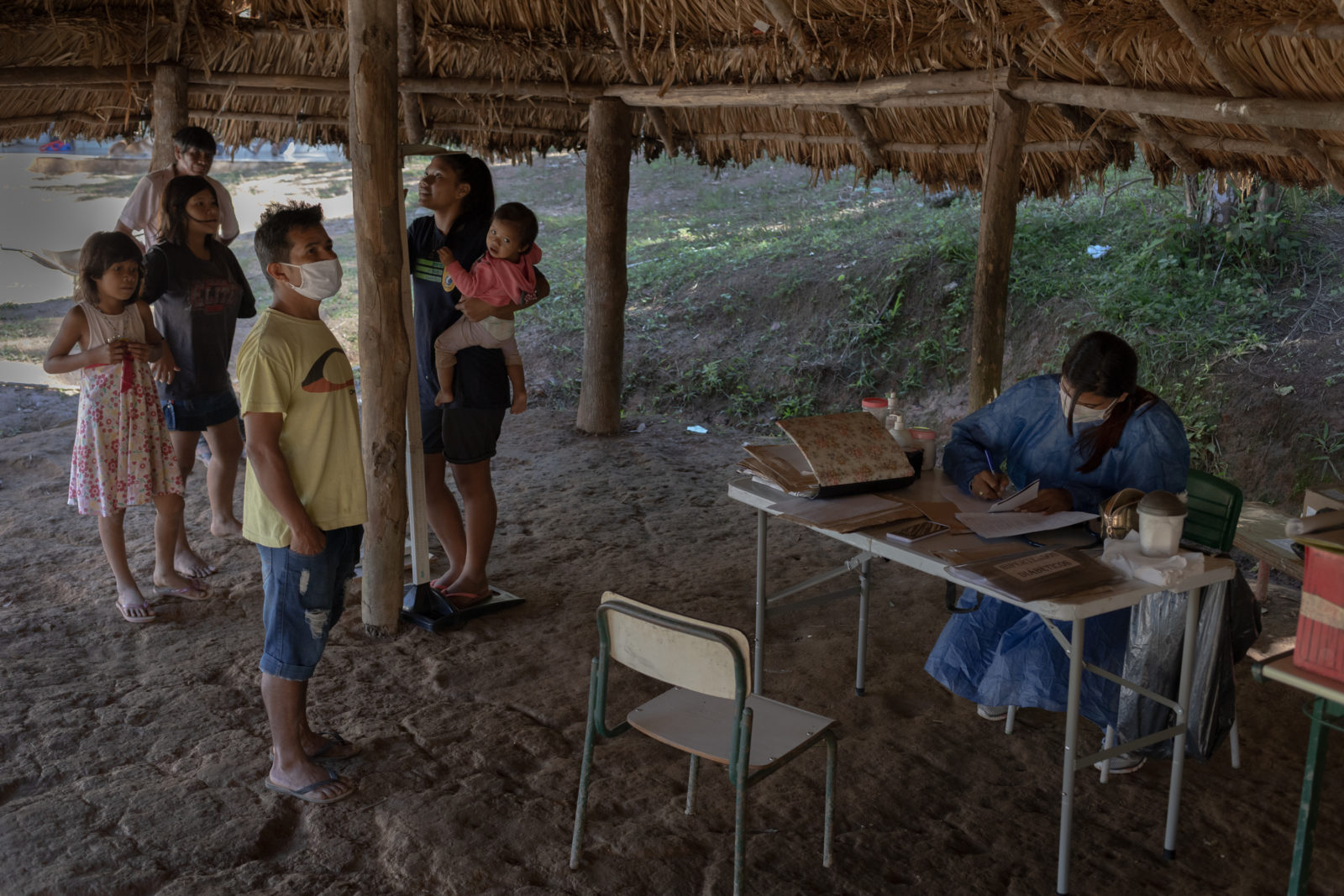

Before heading out for the day, Viegas and the rest of her team stop to pick up supplies. They don’t have a designated space to see patients in the villages, so when they can, they set up a tent. Home visits are common, too, when they need to check on patients who aren’t used to seeing a doctor.

Viegas has been working in the Miracatu region for four years, so residents know her well. She’s also Indigenous, a member of the Guarani Ñandeva group from the neighboring state of Paraná, and her understanding of the culture helps her connect with her patients.

While SESAI is tasked with providing Viegas and her team with the necessities to do their jobs, resources are scarce and supplies are only replenished every three months. As her work increased during the pandemic, so did her need for gloves and masks. Viegas frequently has to make do with what she has. Sometimes she and her team end up buying their own.

“We have to keep working, and we have to protect ourselves,” she says. “And we have to protect them too.”

But that’s not the hardest part of her job. What people don’t realize, she says, is that the guidelines for staying safe during the pandemic—especially social distancing and quarantining when sick—are almost impossible in the villages where she works.

Communal living is common in several Indigenous cultures, and many groups are nomadic, going from village to village on a regular basis. In the Guarani Mbya communities where Viegas works, one-room homes are often shared by a handful of relatives. Kitchens are shared too, and everyone eats together.

“Our fear is that if the virus enters the village,” Viegas says, “it will spread very fast.”

So far, the population of roughly 500 people she cares for have seen about 80 mild cases of COVID-19 and one death. She hopes they’ll be able to hold the virus at bay, but knows the difficult situation the country is in won’t come to an end soon.

“Unless we have at least half of the population immunized, the virus will continue to circulate a lot,” Viegas says. “I still don’t see a lot of light at the end of the tunnel.”

Jill Langlois

Jill Langlois