Bri Adams always imagined she would have three children, just like her parents did. At 33, she has a son, age three, and a daughter, one and a half. Though Adams said she and her husband would like another baby, they decided that they can’t afford one.

Even on a combined salary of $250,000 a year.

Adams and her husband, both college graduates with full-time jobs, earn far more than the median United States income of $80,610. Yet, their relatively high salaries — hers from a tech company, his from the U.S. State Department — aren’t enough, she said, to offset the $3,000 monthly mortgage on their townhouse in Falls Church, Virginia, a suburb of Washington, D.C., and daycare costs of $2,000 a month per child.

“I’m the third of three kids. So anytime I pictured having a family, it was always with three,” Adams said. “Unfortunately, despite having the space in my home and the space in my heart and my partner’s heart, we just cannot afford a third child.”

Adams’ story of longing and disappointment is commonplace in the United States, one of many countries facing a notably reduced birth rate that threatens population and economic growth. As the majority of women moved into the workforce in the past half century, and as the costs of having and caring for children have grown, the size of the average family has shrunk.

Adults are not replacing themselves with new generations, a reality that is particularly problematic for countries like the U.S. that depend on a young workforce to support an aging population.

Last year, the fertility rate in the U.S. stood at 1.6 births per woman, a drop from the 1.99 births per woman 30 years earlier, according to the United Nations. The U.N. reported that in 2024, the global fertility rate was 2.2 births per woman, down from 4.8 in 1970. In four countries — China, South Korea, Singapore and Ukraine — the fertility rate has dipped below 1.

“Fertility rates are falling in large part because many feel unable to create the families they want, and that is the real crisis,” said Dr. Natalia Kanem, executive director of the United Nations Population Fund, which recently released a survey of 14,000 adults in 14 countries. Nearly one-fifth (18%) of respondents under 50 said they didn’t expect to have the number of children they want. More than half blamed economic barriers.

U.S. fertility rates: How do you incentivize a ‘baby boom’?

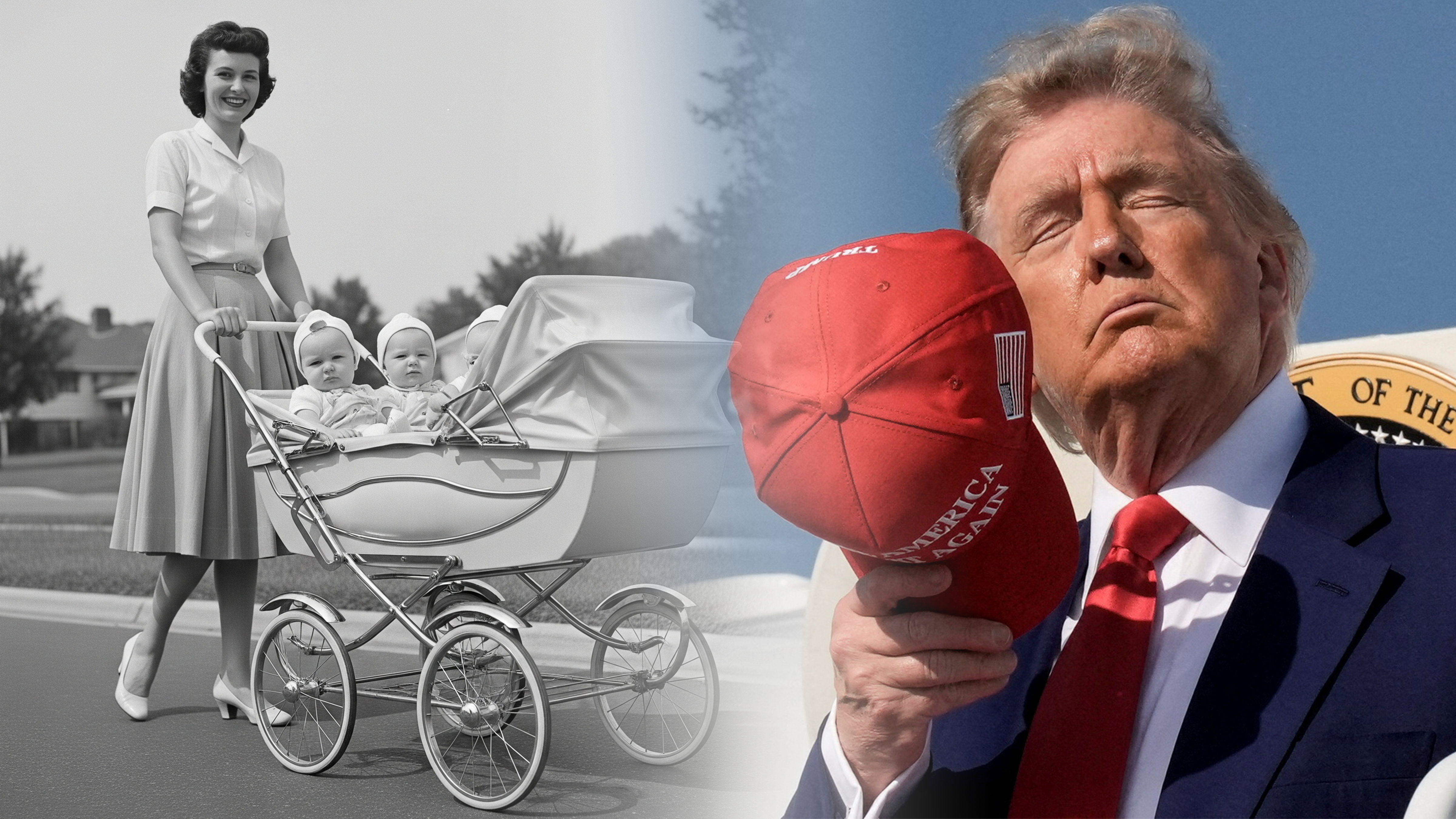

During his campaign last year, President Trump said he would take steps to increase the birth rate, declaring, “I want a baby boom.” Vice-President JD Vance also wants to see more babies born in the U.S. and Trump’s former top adviser, billionaire Elon Musk, seems to be on a political and personal quest to repopulate the planet. (He has acknowledged fathering 14 children with four women.)

The administration has reportedly been hearing from conservatives peddling policies that would reward parents for having babies with tax incentives, one-time baby bonuses and actual medals (the latter, for mothers of six). The massive tax and spending bill that Trump signed into law this month included the creation of $1,000 investment accounts for babies born from 2025 through 2028, though the money cannot be withdrawn for 18 years.

Women’s-rights advocates, however, say those measures fail to offer the level of support working parents actually need.

“Moms don’t need incentives. We need support every step of the way,” said Erin Erenberg, CEO and co-founder of Chamber of Mothers, a nonpartisan grassroots organization, with which Bri Adams volunteers. “I say that it’s no secret what will lead to more babies. It’s these three things: paid family medical leave; accessible, affordable child care; and improved maternal health.”

Across the political spectrum, advocates for parents in the U.S. agree that people would have more babies if the costs weren’t so prohibitive. They want government policies to enable parents and would-be parents to build the families of their dreams. But they disagree on how to do this.

“If we’re going to have a day-care subsidy, I think we should also have a homemaker allowance to keep parity, to avoid discriminating,” said Lyman Stone, director of the Pronatalism Initiative at the Institute for Family Studies. “But I would just say, in general, we shouldn’t do either of these. We shouldn’t subsidize day care. We shouldn’t subsidize staying home. We should just give parents cash and let them make the choice on what’s best for their family.”

Pronatalists are (predominantly) conservative activists who encourage women, primarily married women, to have more babies. Yet even among pronatalists, there are differences of opinion on why and how to grow the population.

“You’ve got people who are worried about economic decline, dependency ratios, paying for Social Security, innovation, any of these things. We’ve got people who are worried about loss of culture, civilization, civilizational decline, the end of certain communities. And then you have people who just think it’s bad because people aren’t getting what they want,” Stone said.

In a blogpost written last June, Stone singled out one segment, “communitarian pronatalists,” which he said “covers an enormous range of political territory, from simple love of family to the bonds of faith and creed, to — in some of the worst cases — racial supremacism and genocide. It is this last strand of communitarian pronatalism that has given pronatalism, writ large, a bad name to many demographers.”

The Trump administration has not specified how it would inspire parents to have more babies beyond the cash incentives outlined in the new law. In response to an interview request for this story, the press office emailed a quote from spokeswoman Taylor Rogers, who echoed some of the pronatalist stances that Stone described.

“President Trump believes parents know how to best raise their children, and this administration is pursuing policies that empower parents with the flexibility to make the best choices for their kids while lowering child care costs,” Rogers wrote.

Tackling population decline is a global challenge

It is hard to cajole women to have more babies.

Countries have created a plethora of programs to increase fertility in recent years. Some have stopped population collapse, at least temporarily, but none has changed the general trajectory of decline, said Jennifer Sciubba, President and CEO of the Population Reference Bureau, a nonprofit research organization.

“Anyone who’s tried this, especially if their goal is to reach replacement again, there’s no one who’s ever done that. It may be that they prevent it from going lower faster, that’s possible, but not everywhere,” Sciubba said.

Nordic countries, she noted, have offered paid parental leave, a policy favored by feminists, and yet Finland has a low fertility rate of 1.3 children per woman, Sweden and Norway 1.4, and Denmark 1.5. Child tax credits, which allow parents to reduce their tax burden based on their number of dependent children, have also not done the trick, she said.

South Korea is the poster child of low fertility. The east Asian nation has spent roughly $270 billion on policies and credits and cash bonuses, Sciubba said. In 2024, its birth rate was just 0.73 children per woman. (This April, birth rates reportedly rose at their fastest rate in 34 years, a shift attributed largely to a post-pandemic increase in marriages.)

There is one thing that unarguably boosts a nation’s population, even when birth rates slump: immigration. According to Sciubba, it is only because the U.S. attracts a high number of immigrants that its population has not peaked. “It will solely depend on our immigration levels as to how much the U.S. population shrinks or grows this century,” she said.

Yet curtailing immigration is a centerpiece of Trump’s agenda. For the president of the National Partnership for Women and Families, Jocelyn Frye, these immigration policies reveal an ugly truth about some pronatalists: racism.

“If it was about birth rates, then you wouldn’t be pursuing all sorts of regressive policies against communities that have higher birth rates, like immigrant communities, right?” Frye said. “At the same time [the U.S. government is] talking about increasing birth rates, they’re also talking about kicking out groups, different pockets of people who are disproportionately Black and brown folks…”

Indeed, women’s-rights advocates say, a number of Trump’s policies will do more to repress the birth rate than to increase it. That includes reducing access to family planning and reproductive health — including abortion — which enable people to have children if and when they choose. It also includes cutting Medicaid, a federal and state-funded program that pays for more than four in 10 births in the U.S.

“You have to sort of look at the full range of policies that the administration is trying to put forward, and then you begin to get a picture,” Frye said. “Their agenda is very narrow, and it’s rooted in a perception about where women are supposed to play a role, and their view is that women’s role is to have children and to stay at home, and everything that they are doing is with that in mind.”

Want more analysis from The Fuller Project? Subscribe to our newsletter.