Behind the tinted windows of a Greyhound bus rolling down the over 600 miles of highway between Wichita, Kansas and San Antonio, Texas, sat then-15-year-old Kristen Powell, with little more than a bus ticket. Although she was on the way to see her mother, Lisa, posters of the teen smiling for the camera would soon appear across the internet, labeling her a runaway. Powell says she ran away from foster homes and from her father’s house more times than she could remember, and police searching for her was typical. Many of these run-away attempts (she had been in foster care since she was 13) ended similarly, with the dark-haired teenager in shackles before a judge would order her to be sent to a juvenile facility.

“[Judges] say, like, ‘We’re trying to protect you from yourself,’” says Powell. “But for me, they weren’t protecting me. They were just trying to lock me away to fix the problem.”

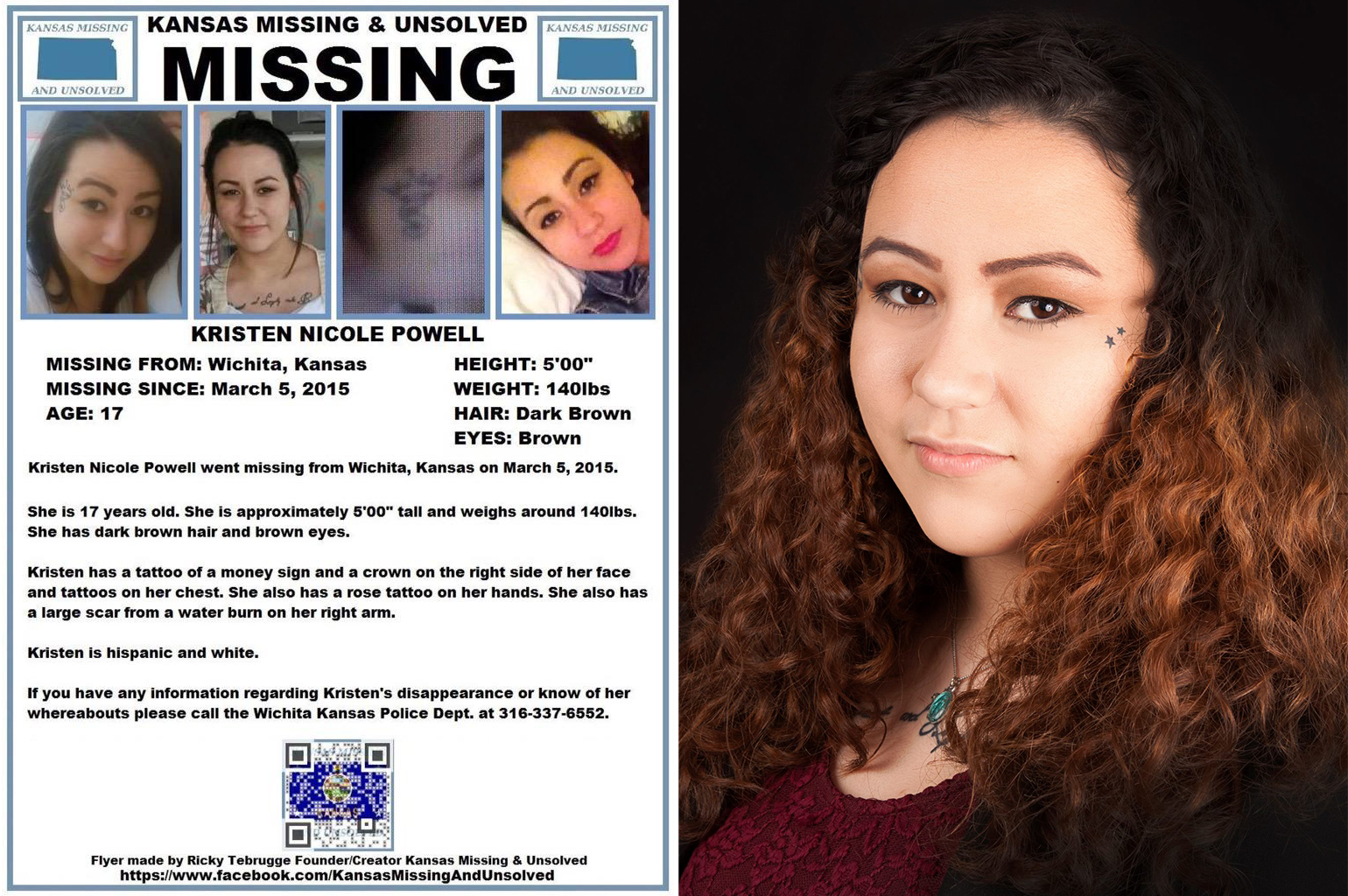

In Powell’s case, going to see friends or her mother, who didn’t have custody of her, was defined as “running away” and could result in her detainment. Her story isn’t unusual in the juvenile justice system. Girls—in particular, girls of color and girls who have suffered trauma—are overrepresented among those incarcerated for committing status offenses in violation of what are called valid court orders, experts say. (Powell identifies as white and Mexican.)

“Girls are disproportionately likely to be charged with status offenses… Things like missing school, running away, [missing] curfew, and the behavior around not complying with parental rules,” says Naomi Evans, executive director of the Coalition for Juvenile Justice. “Those are the behaviors that we are more likely to punish girls for than boys, in part because of our expectations around what society thinks girls should behave like.”

Indeed, despite accounting for just 15 percent of all incarcerated youth, girls make up roughly 38 percent of youth incarcerated for “status offenses,” and the majority of youth incarcerated for running away, according to the Youth First Initiative.

By age 17, Powell, who is now 23, had been arrested and charged at least twice for running away alone, and five other times for running away in addition to other crimes. In total, Powell was arrested over 14 times during her childhood.

Powell’s history with the juvenile justice system began at age 13 in 2010, when police arrested her for engaging in what police deemed “prostitution.” Powell ran from her father’s house, where she felt unsafe, she says. Donald Davis, a child sex trafficker she met at a local children’s shelter, ended up trafficking Powell for a month, before police found and arrested Powell on Christmas day in 2010. (Davis was later convicted of trafficking.) When she was released in 2011 a judge placed Powell in foster care and gave her a no-run order, also known as a valid court order in the juvenile justice system.

Detention wasn’t always the response to youth status offenses. When the Juvenile Justice and Delinquency Prevention Act, the main federal law governing the youth justice system in the U.S., was first enacted in 1974, it made clear that no youth should be incarcerated for status offenses. But an update to the law in 1984 allowed judges to issue valid court orders that act as an exception to that rule. This resulted in stories like Powell’s, in which girls are punished for trying to escape the same difficult situation over and over because a judge ordered them not to run away.

“You can’t take a child and try to strip them away from [their mom],” says Powell. “All the stuff I was running away from was really just [me] trying to [be with] those people that cared about and invested in me as a kid.”

Judges’ motivations for using valid court order exceptions range from “frustration” with being unable to prevent girls from repeatedly running away (often from what they consider bad home environments) to the idea that incarceration will protect vulnerable youth, says Francine Sherman, a professor specializing in juvenile justice at Boston College Law School.

Judge Judith Ramseyer, former chief of the King County juvenile court in Washington state, says judges often see valid court orders as their only tool to get status-offending juveniles to comply with orders to do things like attend school, go to counseling, or undergo substance abuse treatment. Juvenile detention can be used two ways, she says: “Either coercively, to get their attention, or therapeutically, to have them meet with counselors” or other support service providers.

Though Ramseyer says punishment isn’t the most “effective” approach when working with teenagers, she notes it can be helpful in “interrupting really dangerous or destructive behaviors.”

“The parents come to us and say, my 15-year-old daughter is living with a 40-year-old man and they don’t know where she is,” says Ramseyer. “[D]etention is the only remedy that’s available to the court, [insofar] as the court order having any teeth.”

‘Sexist attitudes’ and racism in juvenile courts

Advocates in the juvenile justice space consider valid court orders, like the no-run order Powell had, to be a legal loophole, enabling judges to detain youth for non-serious and often trauma-related actions such as running away—offenses punishable only because they’re committed by minor children.

By keeping this legal tool available, advocates argue that not only do the issues leading girls to commit status offenses go unaddressed, but also that further trauma is inflicted upon already vulnerable girls.

“There are absolutely sexist attitudes that impact the way girls are treated in the system,” says Yasmin Vafa, executive director of youth advocacy program Rights4Girls.

Yet families seeking resources like counseling, mentorship programs or mental health services for their children are often steered towards the juvenile justice system. Malaika Eban, community strategy lead and restorative facilitator at the Legal Rights Center, says she talks to families all the time who’ve been told that their child can gain access to services only after they’ve been arrested. “It creates this perverse reality where families are watching their children involve themselves in potentially dangerous situations,” she says, “praying and hoping that at some point, the system [will catch them].”

But once parents or other authority figures involve the justice system in their children’s lives, the consequences are often entirely out of their hands.

In 2020, Grace, a 15-year-old Black girl, was detained for months after violating a court order put in place by a Michigan judge following a physical altercation between Grace and her mother, who ended up calling the police, according to reporting by ProPublica. The charge that landed Grace (a pseudonym used in the article to protect her identity) in jail was a failure to complete her homework in violation of the judge’s court order, a decision that both Grace’s mother and experts said reflected “systemic racial bias.”

“Our system fails Black youth, especially Black girls,” says Riya Saha Shah, managing director of the Juvenile Law Center.

As of 2020, Black girls are the fastest-growing segment of, and are overrepresented in, the juvenile justice system, according to a report released by the Center for Court Innovation. Racial disparities throughout the system are also evident in how Black girls account for a disproportionate share of female status offender cases, according to a Office of Juvenile Justice and Office of Delinquency Prevention 2019 report. And a 2020 study in the Children and Youth Services Review found that roughly one in three African-American girls in detention at the time of the study were there for status offenses.

During the coronavirus pandemic, as jurisdictions throughout the country have released many young people in detention to prevent the spread of COVID-19, persistent racial inequities in the juvenile justice system have increased, says Evans of the Coalition for Juvenile Justice.

Advocates also worry that the downstream effects of COVID-19, such as increases in sexual and gender-based violence and child abuse, could lead to a rise in girls, in particular girls of color, being detained for status offenses because trauma is major pathway for girls entering the juvenile justice system, says Vafa.

The juvenile system often exacerbates the issues girls have before being detained, she says. Certain practices in youth detention centers, like the use of restraints and strip searches, can be triggering and re-traumatizing for young female survivors, according to a Georgetown Law School Center on Poverty and Inequality report.

This played out for Powell when she entered detention. “I just got trafficked, then you want me to do this rape kit thing? And now you want me to get stripped down in front of a stranger? It was super traumatizing,” she says. “When you’re in the system, they [never address] the trauma that the system brings. So I never felt like I processed my traumas from the system until I aged out.”

From commonplace to abolished: one state’s effort to reform VCOs

Washington state now offers the clearest example of modern reform of valid court order exceptions, its use having gone from the most prevalent in the nation to almost nonexistent.

Valid court order exceptions aren’t used equally across the country, and their use is changing, giving advocates and at-risk girls hope for further reform. Only five years ago, in 2016, seven states accounted for a disproportionately large percentage of valid court order use nationally—chief among them Washington state, by far the most frequent user, with 1,723 instances, more than double the second biggest user, Arkansas, with 832.

Washington state senator Jeannie Darneille cites the state’s 1995 “Becca Bill” as a driving force behind the prior use of valid court order exceptions in the state. The bill, which requires children to attend school full-time or possibly face court referrals, was nicknamed for a 13-year-old girl who’d repeatedly run away from home and a drug treatment facility before a man who paid her for sex murdered her in 1993.

While the law aimed to protect runaways like her by implementing serious consequences for skipping school, it led to Washington state incarcerating 30 percent of the nation’s status offenders in 2013, Darneille says, which disproportionately affected Black, Latino, and Indigenous youth. In 2019, she proposed a legislative change to eliminate the use of valid court order exceptions in the state.

The Superior Court Judges’ Association lobbied hard against the bill, convincing legislators that children would suffer from homelessness and death if it passed, Darneille says. The law passed with a phased approach to ending valid court orders, preventing their use entirely by July 2023. Darneille says the state is considering more “therapeutic options” for youth status offenders, like specialized foster care placements and facilities that are more like “group service programs” than detention centers.

Judges’ objections continue to stymie valid court order exception reform in states like Virginia and Tennessee. An attempt to reform these laws at first stalled in Virginia, due largely to resistance from judges, says Rights4Girls’ Vafa, but a bill sponsored by Democrat Don Scott passed in the Virginia House in February and currently sits in the state senate committee. In 2018 in Tennessee, judges’ opposition impeded the passage of reforms championed by the governor at the time, Republican Bill Haslam.

At the federal level, phasing out valid court orders from the Juvenile Justice and Delinquency Prevention Act has also faced pushback—primarily from U.S. Senator Tom Cotton of Arkansas, who in 2016 characterized status offenses by juveniles as “contempt of court,” according to a Juvenile Justice Information Exchange report. (His office did not respond to a request to comment for this story.) After his intervention, a 2018 update to the law limited judges’ abilities to implement valid court orders yet continued to permit them.

In Kansas, Powell now works with and advocates for current and formerly incarcerated youth at the Coalition for Juvenile Justice. Now a mother of three, she’s reunited with her own mother and plans to go to law school in the fall of 2022. She hopes to work to change the juvenile justice system and protect incarcerated youth after graduating with her bachelor’s degree in criminal justice from Wichita State University, which she is on track to do this December.

“Any way that I can lift up my family or lift up young people… with the work that I’m doing” is her priority, says Powell.

Jessica Washington

Jessica Washington