In 2004, Kenya became the first country to abolish point-of-sale taxes on period products, becoming a world leader in addressing so-called period poverty — the inability to access menstrual products and hygienic facilities. Since then, over a dozen other countries have followed suit, according to research from Thomson Reuters Foundation.

Today, policymakers in Kenya and elsewhere are backtracking, either repealing tax reprieves or introducing new taxation schemes.

Kenya had planned to introduce an eco-tax on sanitary pads this year — an enormous burden for Kenyan women, at least 65 percent of whom cannot afford menstruation products. Other countries like Tanzania and Nicaragua have also reintroduced value-add taxes (VAT) on sanitary products that they had repealed just a few years ago, causing expensive whiplash for women at the cash register.

The Kenyan proposal, which included the period product and other tax increases, was met with widespread outrage. A youth-led protest movement quickly went from condemning the hikes online to storming the capitol and clashing violently with police, leaving more than two dozen dead and hundreds wounded.

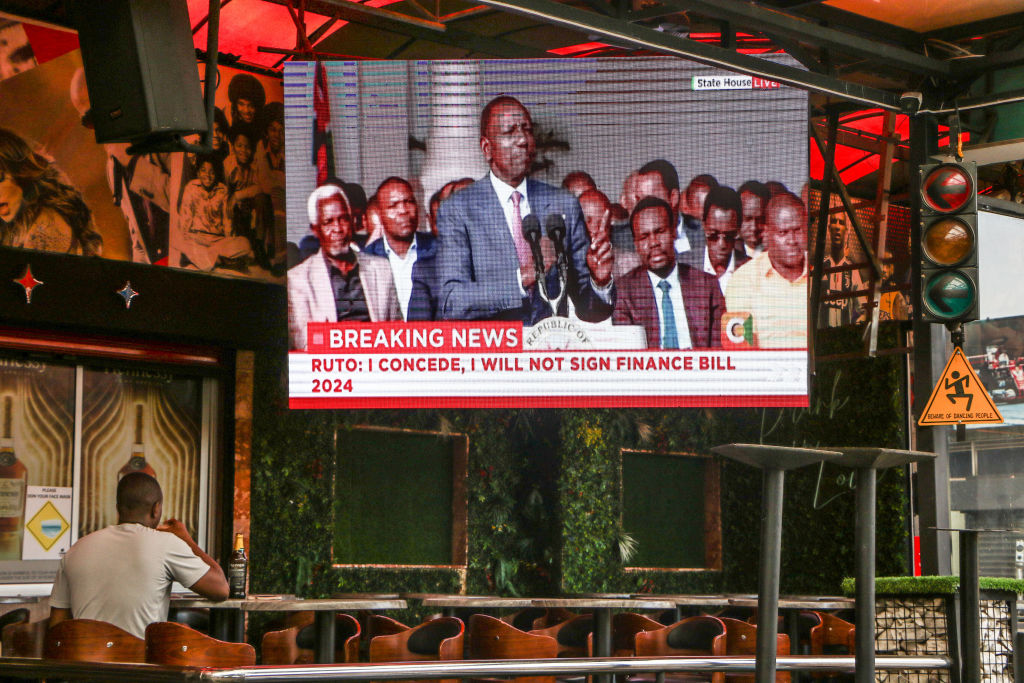

Surprised by the intense resistance, Kenya’s parliament backtracked on its backtracking. Legislators amended the eco-tax, removing it from locally-made sanitary pads but keeping it in place for imported pads. But this move failed to impress women’s groups, who pointed out that most sanitary pads used in Kenya are imported. With protests escalating over this and other issues, President William Ruto withdrew the tax proposals on Wednesday. With parliamentarians insistent on the new taxes as a way to reduce national debt, political observers expect this reprieve to be temporary.

Meanwhile, most Kenyan women can still barely afford period products. In Nairobi’s Kawangware neighborhood, a low-income area full of tin-shack households and small businesses, shopkeepers open up packs of sanitary pads in order to sell each pad individually. Most of their customers can’t afford to buy a full pack.

“I must sell the pads per piece, [instead of packs] every month so that they can afford it and go through their menstruation with dignity,” says Susan Wangari, a shop owner.

Globally, at least 500 million people lack access to affordable period products and adequate facilities for menstrual hygiene, according to the World Bank.

In the United States, each state manages menstruation product tax differently, with 20 states still imposing this extra cost. The movement to address this issue has gained steam lately, but the only federal bill to protect against period poverty has stalled, even though one in four teens and one in three adults struggle to afford menstrual products. Disturbingly, a whopping 52% of American women say they use products longer than recommended in order to stretch their use, despite hygiene worries.

A handful of groups like Aunt Flow, PERIOD. and Alliance for Period Supplies work to help bypass the tax problem by getting free menstruation products in the hands of those who need them.

“My job is not done until period care is just as ubiquitous as toilet paper and paper towels in the washroom,” says Claire Coder, founder and CEO of Columbus, Ohio-based Aunt Flow.

Coder’s organization works with other businesses and governments to make high-quality period products available for free. Their mission is simple: to help ensure no one ever has to worry about getting their period in public. But doing so means navigating the patchwork of different state laws and priorities across the U.S.

From Google offices to every public school in Utah, Aunt Flow sells period products in bulk, as well as simple wall dispensers, to other businesses who then provide the products for free.

With a focus on academic institutions, Aunt Flow has a presence in 750 schools and 150 universities, providing free period products to over 2 million girls in the U.S. Coder says her organization is not only making a difference in terms of access, it’s also helping reduce stigma around menstruation.

“You can feel really good about starting your period unexpectedly rather than turning it into a day-ending fiasco,” she says.

A lot has changed since she started the business in 2016.

“I was spending all of my time and energy explaining to people why it was important to offer accessible period products in bathrooms,” Coder says.

Today, 26 states require schools to offer period products for free.

“We’re not asking for flowers in the bathroom,” Coder said. “We’re asking for a class two medical device, which are tampons.”

*Erica Hensley contributed reporting.