When Marilyn Mendoza took over as the education justice organizer with Make the Road in Jackson Heights three years ago, she noticed that many of the Latina immigrant mothers in her parent group Comité de Padres en Acción craved a safe place to vent.

So Mendoza opened up about her own battle with depression as a child to broach the topic of mental health.

And though at first she received well-intentioned but religious-based comments from some, the women also began to share — about difficulty dealing with not only their children’s anxieties, but their own.

Mendoza quickly put together workshops on self-care and started an art therapy group.

But that was before COVID-19.

Once the pandemic hit, mothers in the group dealt with job loss, remote learning, cramped living spaces, abusive partners and disproportionate deaths of family members.

And due to barriers like immigration status, cost, and lack of interpreters or translation — some Latina women do not speak Spanish as a first language — “they didn’t know where to go or where to seek assistance.”

In November, the Citizens’ Committee for Children released data showing what many clinicians and experts on mental health in the Latino community already knew: Latina mothers in New York City are suffering, and the support provided by the city isn’t cutting it.

Roughly 42% of Latina women with children at home in New York City report symptoms of anxiety or depression, according to the CCC’s analysis of the Census Bureau’s Household Pulse Survey.

“Latina women have always had a higher prevalence of depression in comparison to other women,” said Dr. Rosa Gil, director of Comunilife, a nonprofit focused on mental health and housing services for the Latino community. “I think that challenge has gotten much more critical for Latina women due to the pandemic.”

Issues Compounded

The survey, conducted between April and July of 2021, found that Latina women with children at home were much more likely to report these mental health symptoms than any other group, including Latino men with children at home, 30% of whom also reported symptoms of anxiety and depression during that period. Roughly 36% of both white women and Black women living with children reported symptoms of anxiety and depression.

“We were in the epicenter of the epicenter of the outbreak,” said Mendoza, whose program runs out of Jackson Heights in Queens.

During the height of the pandemic in the spring of 2020, Latinos in New York City were dying at twice the rate of white and Asian New Yorkers, according to data from the Department of Health and Mental Hygiene.

Gill says grief from losing loved ones during the pandemic compounded many of the pre-existing mental health issues among Latina mothers.

Economic factors also played a significant role, said Gill. Latino families with children were more likely than any other racial group to report loss of income, according to the CCC report. Thirty-five percent of Latino families lost income from April to July, compared to 19 percent of non-Hispanic white New Yorkers.

Data from August showed that Latino workers in New York City had significantly higher unemployment rates than white workers. And national data from the UCLA Policy & Politics Initiative found that Latina women suffered the largest drop in employment of any group in the U.S. during the pandemic.

It’s a “perfect storm,” said Mary Adams, director of mental health and wellness at University Settlement, which provides family medical services to those living on the Lower East Side.

“So many of these women were holding their families together,” said Adams. “They were losing jobs and not replacing their income and, in some cases, may not have been eligible for benefits.”

Many benefits, like child care, were already difficult to access before the pandemic.

In November, THE CITY and The Fuller Project found that 55% Latina women with children reported being out of a job well into the city’s pandemic recovery, a number driven largely by child care issues.

Related: Women With Children Having Harder Time Re-entering NYC Workforce

A lack of paperwork makes it hard to access other social supports.

“There are some vouchers that the city and the state provides. But they request a lot of things our families don’t have — one of them being Social Security numbers, pay stubs,” said Mendoza.

And distrust of mandated reporters — professionals like social workers, teachers and doctors, who are required to call in suspected neglect or abuse to the state — can be particularly difficult for Latina women who are undocumented, Mendoza added.

Strength in Numbers

One thing organizations like Masa and Make the Road have found helpful: Creating groups where moms feel comfortable sharing and supporting each other.

Padres en Acción, or “Parents in Action” in English, is one in The Bronx. (A separate but similarly-named counterpart to the Jackson Heights group.)

The group of caretakers — mostly women — was created at Masa, a South Bronx nonprofit focused on serving Mexican and Central American New Yorkers, many of whom are Indigenous and whose first language is neither English nor Spanish.

In March 2020, the group was focused on a campaign against bullying in schools. But that quickly changed when the COVID-19 pandemic slammed into the borough.

For one mother, the turning point was when she began to worry about changes in the mental health of her cooped-up teenage son. So she went to Padres en Acción to talk about it.

There, she found that she and her son weren’t alone in dealing with the fallout of death, job loss, and isolation.

And many of her fellow parents realized that they too wanted help with the pressures of navigating uneven communication from schools, income barriers, language access. Frustration with being unable to help children with remote schooling technology was “a big source of stress,” said Aracelis Lucero, executive director of Masa.

“One of the biggest burdens…especially for immigrant families, and the reason why they migrate here, is a better life and future for their children,” she noted.

The parent-led group issued a set of demands to the District 7 schools superintendent in the South Bronx: Improve communication to immigrant children and their parents about what social-emotional supports were available to the entire family, to create a plan that “is equitable and available to everyone,” and to train all staff to recognize kids who need help.

“We asked that they inform all parents about the help,” said the mother, who requested anonymity because she wasn’t authorized to discuss the group’s issues publicly. “That they have access to that information — because in the Department of Education they said that if you or your child needed help you could ask for it. But our parents didn’t know that!”

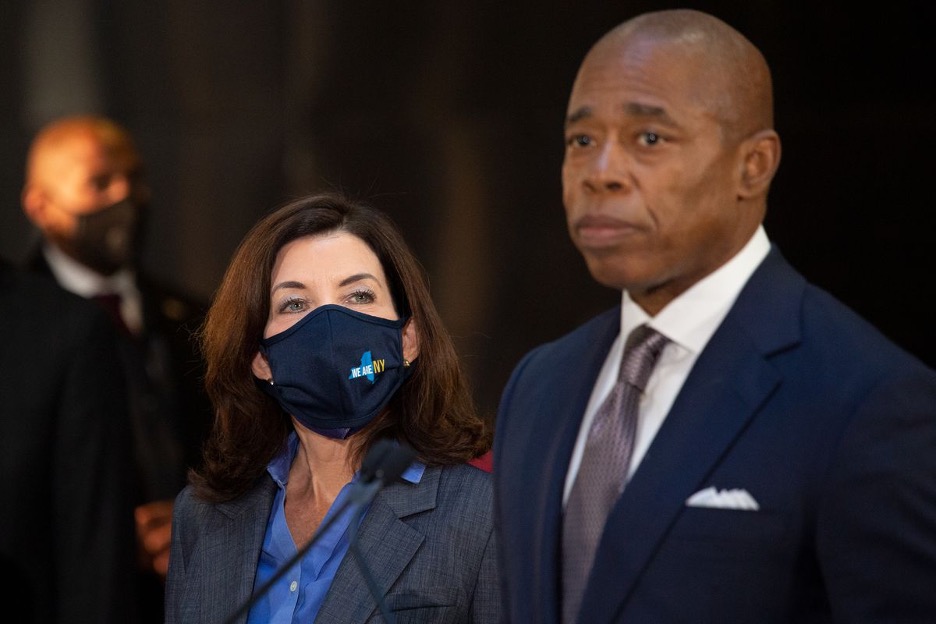

As the omicron variant has overwhelmed the city, she wants Mayor Eric Adams to take more decisive action to lower all the barriers to mental health care that her own family and community still disproportionately face.

“He’s always talking about how there won’t be differences [in treatment] between different communities,” something that just hasn’t been true, the mother told THE CITY in Spanish. “Because we’ve realized during this pandemic that there are differences and that equity in reality doesn’t exist.”

Efforts by de Blasio Administration

The administration of former Mayor Bill de Blasio made strides in improving access to mental health services, said Mary Adams. In 2016 the former mayor created NYC Well, a hotline that connects New Yorkers to free mental health services.

Since its inception, the hotline has responded to over a million messages from New Yorkers reaching out for support for themselves or others. By focusing on mental health care, Adams believes de Blasio’s administration helped to destigmatize the issue, which helps people receive the care they need.

“New York City spends more time and energy on mental health than others, and the de Blasio administration did really highlight mental health,” she said. “But there’s still much to be done.”

Masa also reported that it recently began two groups dedicated to undocumented youth and parents’ mental health needs — funded through the city Department of Health and Mental Hygiene.

It’s important to address the differences in the mental health, language and cultural needs within the Latina community, said Dr. Pamela Montano, director of the Latino Bicultural Clinic in the Department of Psychiatry at Gouverneur Hospital in Manhattan.

“We have a very diverse population, and that’s the beauty,” said Montano. “But also, it makes it difficult, right? Because we have so many needs on so many levels.”

Low-literacy community members and those who may speak an indigenous language as their first language can find difficulty in accessing ”something as simple as navigating the phone system ‘dial one for this, two for this,’” even in Spanish, said Lucero.

“It’s really hard for like non-native Spanish speakers to navigate that, even if Spanish is a language that is available on the phone. So in general, those are the people that we’re seeing are really being left behind.”

To bring these parents back to the table, Masa’s Padres en Acción group is asking for city services to be in-person once again.

“Because I know there is help, but it’s only virtual,” said the Bronx mother. “And even if they’re free, one can’t just turn up and ask for an appointment for myself and my family.”

What, If Anything, Can the Adams Administration Do?

Focusing on issues like income inequality and access to affordable housing would go a long way toward helping Latina mothers like those in Mendoza’s group, said Gill.

“The reality is that we have a broken mental health delivery system,” she says. “It has to be community-driven, and it has to be driven by social determinants of health, which are the ability to eat and have food on the table and have a roof over your head.”

“I think he needs to partner with the state to really figure out how we can actually address this behavioral health crisis,” said Jennifer March, executive director of the Citizens’ Committee for Children. “And then embed behavioral health services in place-based settings in early education, schools and communities, that function and that are accessible.”

Lucero stressed that the city’s schools need to step up for the parents in her programs and offer more basic support to parents, like language and computer classes.

The Department of Education pointed out it does offer online classes to help parents assist their children with online learning and provide up-to-date COVID-19 information in multiple languages, including Spanish.

However, Mendoza says that mental health services and basic economic and social supports need to be in person, something the mother from the Padres en Acción group also stressed.

And, said Lucero, the city needs a more permanent solution that makes pandemic direct aid “part of the norm, not the exception” for all New Yorkers — including the undocumented and indigenous communities.

“It’s great we have a hotline where people can call in,” said Mendoza. “But now we needed to take it to another level where we’re funding the services, so that they become long-term services for families, for individuals, and that it’s services that are accessible to everyone and anyone, regardless of status or language.”

Mental Health Resources and Self-Harm Prevention:

- 1-888-692-9355 NYC Well Free Mental Support Health Hotline

- 212-684-3264 National Association of Mental Health (NAMI) NYC Hotline

Jessica Washington

Jessica Washington