ISTANBUL—For most of the 19th and 20th centuries, women war correspondents were rare creatures—considered intellectual oddities, more likely to be fetishized than taken seriously as news gatherers.

Even as recently as 2002, Vanity Fair was delighting in the exoticism of such women in its story “Girls at the Front,” which profiled the battle-hardened correspondents Christiane Amanpour, Janine di Giovanni, and Marie Colvin. They had sex appeal and well-furnished London homes, and they made up a small brigade of female journalists jetting off to “whatever hellhole leads the news.”

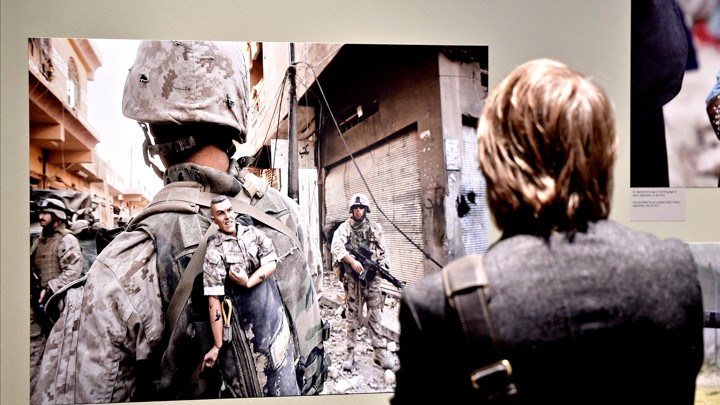

These days, there are so many “girls at the front” that it’s not a story anymore. The New York Times, The Washington Post, and the Associated Press all have female bureau chiefs reporting on ISIS, Syria, Yemen, Egypt, and Libya. In Istanbul, a jumping-off point for covering the region, there seem to be more women freelance correspondents than men. This month’s new film Whisky Tango Foxtrot, in which Tina Fey plays an adrenaline-addicted reporter in Afghanistan, captures how women have broken into the tightly knit, elite foreign-correspondents’ club.

Yet the landscape hasn’t entirely changed. When it comes to winning prizes for their work, for example, female foreign correspondents are stuck in the last century. Ample research moreover points to persistent gender bias across television and print media. In 2011, men penned nearly 80 percent of the op-eds published in most major U.S. newspapers; during America’s 2012 elections, male reporters had more than twice as many front-page bylines in major newspapers as women did. In 2015, men also made up around three-fourths of the guests booked to discuss foreign policy and national security on prime-time cable and top Sunday news shows. Even in articles about birth control, abortion, and other topics relating to women’s bodies, men are quoted more frequently.

How journalists portray the world has real consequences, and the world is being portrayed through a male lens.

When my organization, the Fuller Project for International Reporting, which does multimedia reporting on women in conflict and foreign affairs, analyzed journalism awards recently, we found that male correspondents were recognized and rewarded for their reporting nearly two and a half times more often than their female colleagues among the prizes we studied. Consider this: In the last two decades, even as more women have broken into the field, men still won nearly three times as many Pulitzers as women for foreign reporting. Since the mid-1990s, Britain’s prestigious Foreign Reporter of the Year, which is given out at the British Press Awards, has gone 17 times to men and eight times to women. In the last decade, the Robert Capa Gold Medal Award for photojournalism has been given to nine different men and only one woman.

This trend continues. In the last two years, the Overseas Press Club of America has given 50 awards to men but only 21 to women. The George Polk Awards for international, foreign, and war reporting do little better: They went to 29 men and 16 women over the last decade. Ironically, one of the worst discrepancies occurred in the case of the Martha Gellhorn Prizes, named in honor of the most famous female war correspondent of the 20th century. The organization has awarded prizes to 19 men but only to four women. So even as more women are risking their lives to report on the world, their work is still given less weight.

Prizes signal what the industry values. Efforts to win them can drive decisions on which reporters are funded and for which types of projects. Repeatedly awarding men’s reporting over women’s feeds a cycle that perpetuates the relative authority of men’s voices over women’s. Male journalists quoted four times as many men as women in a study of 352 front-page New York Times stories in the first two months of 2013. (The same study found that female journalists also quoted men more frequently than women, but the imbalance was not as severe.) The imbalance in awards also reinforces the notion that reporting on combat, mission strategy, and violent conflict qualifies as “hard news,” while coverage of human rights, maternal health, sexual assault, and education—which women more frequently cover—is “soft” news.

Read the article here.

Christina Asquith

Christina Asquith