Watch more on this story: Why did Instagram take down this creator’s account?

On July 11, Sam Atalanta opened Instagram expecting to scroll through their account, The Vulva Gallery. The Dutch artist’s colourful, cartoon-like illustrations of vulvas had attracted some 730,000 followers, many hoping to better understand their bodies.

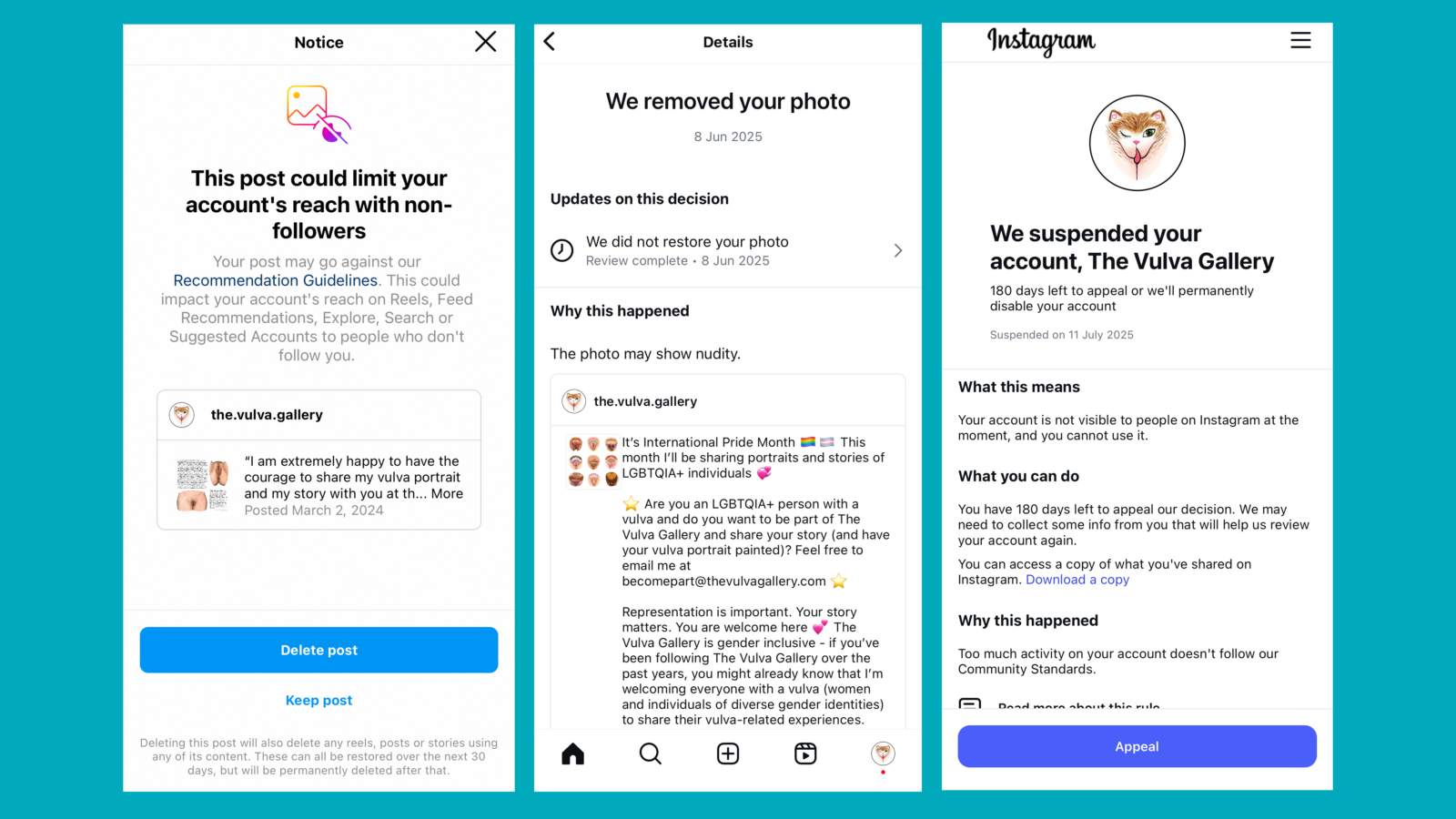

But that day, a message popped up: “We’ve suspended your account.”

Instagram’s explanation was vague. There was “too much activity” that didn’t follow their community guidelines.

Atalanta’s work is clearly art, and their drawings are used as educational materials – both exceptions listed under the nudity guidelines of Meta, the platform’s parent company.

“It’s been so stressful and really saddening,” says the 36-year-old. “I feel like I’ve just been fired without any warning or any way for me to defend myself.”

Atalanta’s drawings have been used as educational tools by the U.K.’s National Health Service and reproductive health nonprofit Planned Parenthood. The project was even featured in Netflix’s hit show “Sex Education”. The Vulva Gallery was nine years of work, the main source of Atalanta’s income and a considerable global community, yet Instagram still pulled the plug.

In recent years, the world’s largest social media companies – almost all of them founded in the U.S. – have been under increasing pressure from lawmakers from Brazil to the U.K and across the E.U. to protect users – especially children – from illegal or harmful content. Often cited examples are posts that glorify violence, genocide, eating disorders and self-harm or includes hate speech, child sexual abuse or pornography.

At the same time, creators who post about sexuality, sexual and reproductive health have accused Instagram and other platforms of removing their content, deleting their accounts entirely or restricting them from reaching non-followers, a practice known as ‘shadow banning’. Digital rights experts say posts that are safe and provide genuine educational value regularly get swept up by systems ostensibly designed to catch harmful content, especially when those systems are driven by algorithms.

And, as The Fuller Project was told, the erosion of rights and freedoms for women and LGBTQ+ people offline is mirrored and amplified online.

“The reach is just exponentially higher: rather than going door-to-door, demanding that you take a Pride flag down…you can now just program an algorithm to censor all Pride flags,” explains Paige Collings, senior speech and privacy activist at Electronic Frontier Foundation, a U.S. nonprofit that defines its work as “defending civil liberties in the digital age.”

Leeza Mangaldas, an Indian sexual health educator, is a source of vital information for her 1.2 million Instagram followers, in a region where such topics are often still taboo. But the content creator says she’s had to delete hundreds of posts. Instagram told her she’d be shadowbanned if she didn’t, she says.

Lately, Mangaldas, 35, says things have gotten “more extreme, more absurd.” Content featuring anatomical diagrams, lipstick-shaped vibrators and vegetables used as stand-ins for genitalia, is getting flagged, removed or resulting in her account being restricted – something, she says, wouldn’t have happened in the past.

“Thanks to AI, the censorship is faster, broader, and frankly, more ridiculous,” she tells The Fuller Project.

Instagram acknowledges using artificial intelligence to moderate content, including to make decisions on whether to remove content. The problem with that, says Mangaldas, is that while it might be able to detect the shape of a sex toy, AI can’t tell the difference between pornography and educational materials.

“I don’t post anything pornographic. I don’t solicit sex. I share medically accurate, culturally sensitive, and visually very tame imagery and information — and yet I’m constantly being penalized,” she says before adding: “I’m not saying it’s a direct cause-and-effect but it’s hard to ignore that the clampdown on sexual and reproductive health content seems to mirror political shifts.”

Social media researcher at Northumbria University’s Centre for Digital Citizens, Dr. Carolina Are, does suggest a link between U.S. politics and censorship on the platforms: “A lot of tech bros are cozying up to the Trump presidency, which is obviously very anti any form of sex education; any form of queerness.”

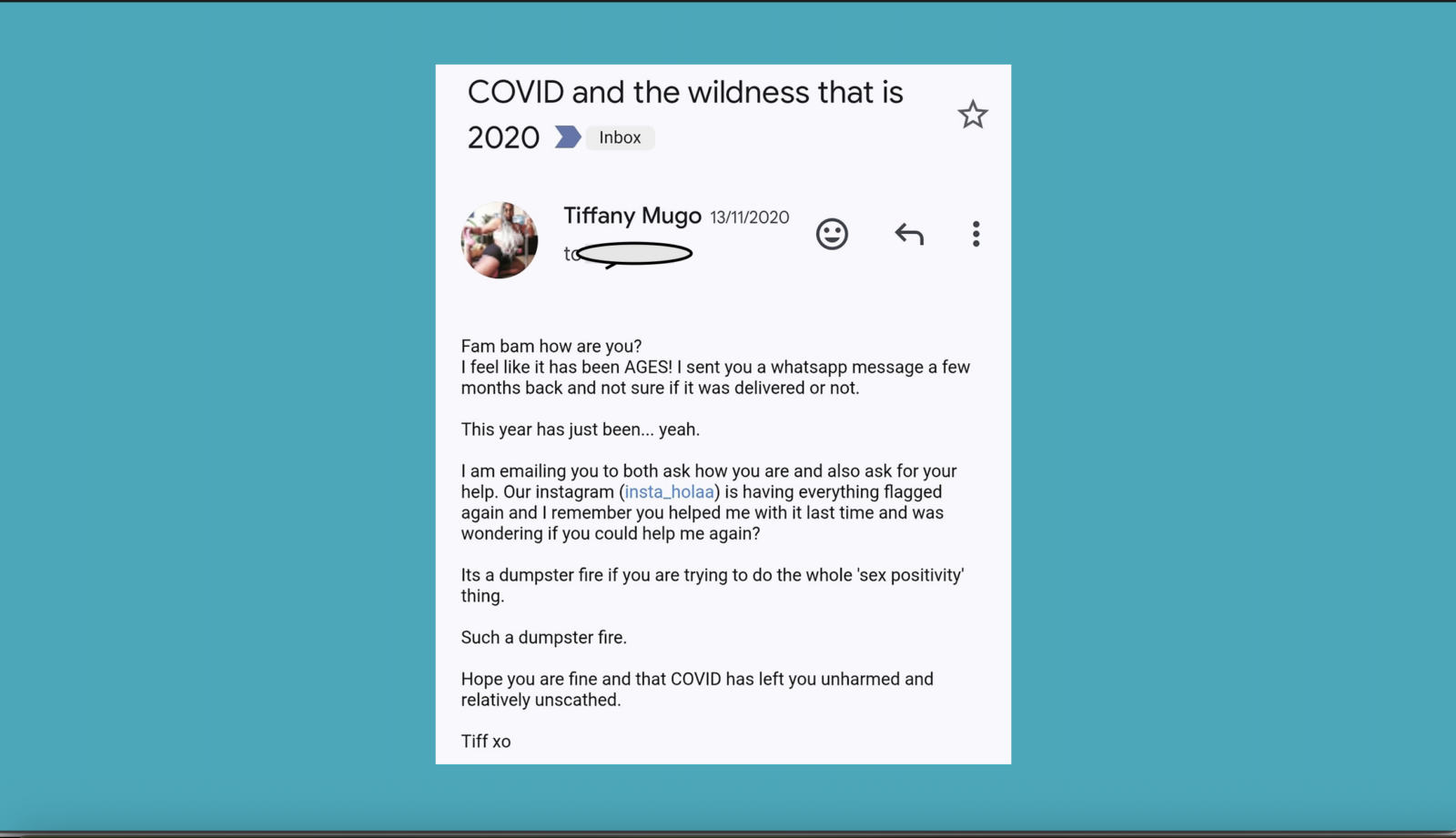

“Everyone I know doing sex education content is being brought to their knees,” says Tiffany Mugo, who runs HOLAAfrica, a digital platform focusing on sex, sexuality and pleasure across Africa.

In 2023, Mugo asked the page’s Instagram followers what seemed like an uncontroversial question: what forms of pleasure did they like? By then, she says she’d become accustomed to posts being deleted or hidden. She’d even fought to have the page reinstated once. But this time, Instagram shut the account down for good, accusing HOLAAfrica of soliciting sex, according to Mugo.

When the team started a new page (losing 10K followers in the process), they posted more conservatively for six months.

“We were so good,” she says. “We were like the trad wife version of sex positivity.”

The content reached more people, but it didn’t sit right. Now, they post what they want. They’re still producing and reposting sex positive content, even if it’s hampered their following – a small win against the algorithm.

Subverting the algorithm

Like Mugo, sex education creators have tried to sidestep shadowbans and censorship.

The aubergine emoji, for example, replaced writing the word ‘penis’. But platforms have caught up. Use that emoji now, says Mangaldas, and your content is likely to be flagged.

From ‘intercourse’ to ‘intimacy’, there’s a whole range of words Mangaldas says she can’t use online. So instead, she’s invented her own vocabulary: she uses “Ghapaghap” – an onomatopoeic Hindi slang word – for ‘sex’. “Kitty cat” stands in for ‘vulva’.

Are, from Northumbria University, is also a content creator who has been shadowbanned for years. But she’s skeptical of these strategies. Not enough is known about the inner workings of the algorithms, she explains, nor is there a swift system in place to help when someone’s page or content is wrongfully removed.

This is something Atalanta has experienced first-hand. When Instagram suspended their account over two weeks ago, all they could do was click the blue ‘appeal’ button and wait. If they could just talk to a human, they thought, they could explain that the account is educational; that its goal is to normalize an often sexualized body part by depicting it in a non-sexualized way. That it’s meant to help people who look in the mirror and think, ‘am I normal?’

“It’s just been silent from Instagram’s side,” says Atalanta.

Neither Instagram nor Meta responded to The Fuller Project’s request for comment.

On the issue of shadowbanning, a Meta spokesperson told The Markup in 2024: “Our policies are designed to give everyone a voice while at the same time keeping our platforms safe…We readily acknowledge errors can be made but any implication that we deliberately and systemically suppress a particular voice is false.”

Deliberate or not, Atalanta argues that “suspending educational accounts like this is censorship because it’s silencing communities and it’s silencing creators and it’s silencing marginalized voices.” The impact of which extends beyond the specific creators themselves to the hundreds of thousands of young people who turn to digital platforms for reliable information about sex, health and relationships.

While young people may be exposed online to “misinformation, pornography, and other types of inappropriate content,” according to the Global Partnership on Comprehensive Sexuality Education, “digital sexuality education helps overcome discomfort and shame that both learners and educators might experience, while discussing sensitive issues in class. Thus, young people report they feel less stressed when asking questions on the internet than face-to-face.”

Yet the reality is that creators don’t own the platforms on which they rely to reach audiences, nor do they have influence over the rules that govern the platform or the motivations of their owners.

“You can rage against the algorithm but the algorithm is what it is,” says Mugo of HOLAAfrica. “It’s a balancing act between playing the game and sort of subverting the game.”