During her marriage to her abusive ex-husband, Freya* sustained multiple head injuries. Her ex-husband punched her in the face and slammed her head into door frames repeatedly, once even hitting her head against the inside of the car while she was driving on the highway, she tells The Fuller Project. He also strangled her and in one instance held her head underwater for so long, she thought she would drown.

“He would come home from work and be angry, and he couldn’t take his anger out on the people he worked with, so he would take it out on me,” Freya says. During what she calls his bad periods, that would happen “a few times a week.” She says she slept with a handgun under her pillow for protection.

Freya was only married to her ex-husband, whom she met while in high school, for less than two years, she says. The last head injury she got from him, the “big one” that put her in the hospital for five days, happened more than 30 years ago. But she’s still suffering from the cumulative effects of repeated head trauma.

Nearly two decades ago, Freya began forgetting the names of people she knew well. She’s experienced depression, light sensitivity, and migraines. Though she’s always been good at numbers, she says she recently started struggling with them, which has affected her work at the front desk of a dental office.

“I feel like I’m constantly evolving,” she says, “and not always in a positive way.”

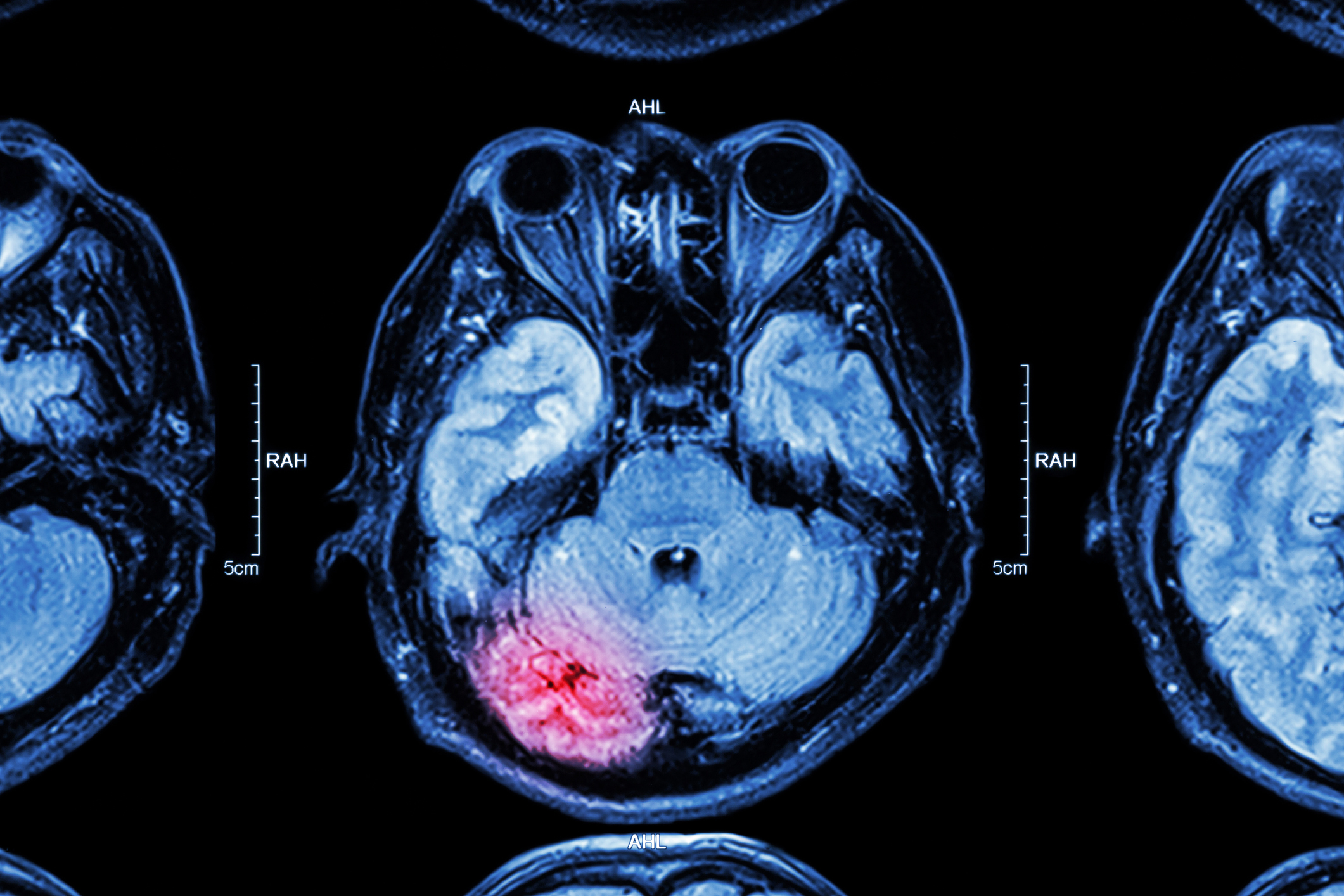

According to the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, these could all be symptoms of a Traumatic Brain Injury, or TBI. While these types of injuries most often come up in the context of professional football players and military personnel sustaining concussions, there’s a third group that disproportionately suffers from TBIs — female survivors of intimate partner violence, or IPV. The little — but influential— research that’s been done on this demographic indicates that it could account for the majority of TBI sufferers in the U.S. However, IPV survivors have been marginalized in TBI research.

***

In a study published in 2003 called “Brain injury in battered women,” Dr. Eve Valera, today an associate professor at Harvard Medical School and research scientist at Massachusetts General Hospital, interviewed 99 women who’d experienced IPV. Seventy-four percent of them reported at least one IPV-related brain injury. Half reported multiple brain injuries by an abusive partner.

Because of the small sample size of her study, Valera says it’s impossible to “extrapolate legitimately” from her findings. But if you consider that one fourth of women in the U.S. experience “severe physical violence by an intimate partner,” according to the National Coalition Against Domestic Violence, that could mean there are possibly “millions and millions” of women walking around with what Valera says could be “undiagnosed, unrecognized brain injury in the United States.”

This would mean the prevalence of the problem in this demographic vastly overwhelms the numbers who suffer from the injury among the 2,000 active National Football League players in the country, while the Defense and Veterans Brain Injury Center reported about 414,000 TBIs among U.S. service members between 2000 and 2019.

The reason for the focus on football players or military veterans in contrast to IPV survivors boils down mostly to gender (most athletes and military personnel studied for TBIs are male) and money, says Karen Mason, the former executive director of Kelowna Women’ Shelter in British Columbia.

“There are no big dollar advertisers in intimate partner violence,” she says, adding there are gaps in women’s health research in general, partly because scientific research has historically been a male-dominated field. “Most of the work that’s been done has been on men and male bodies.”

Valera encountered both a lack of information and funding struggles throughout her research on TBIs and IPV.

She first became interested in the connection while volunteering at a women’s shelter during psychology graduate school in the mid 1990s. At the shelter, Valera heard stories from women about abusive ex-partners stomping or hitting them in the head.

“It seemed obvious that women would be sustaining brain injuries,” she says, but a data search related to her observations came up with nothing. This prompted her to focus her dissertation on the prevalence of brain injuries among IPV survivors and how those injuries affected women’s cognitive and psychological functioning, which eventually led to her 2003 study.

The next step was to look at neuroimaging of IPV-related TBI survivors, but Valera had trouble getting funding. Instead, she received a large grant to study neuroimaging of people with ADHD. While doing that research, a much smaller grant allowed her to “collect some imaging data from women experiencing partner violence… in the background,” she says.

Because Valera’s primary funding came from the ADHD research, it took some time for her to get the TBI data analyzed. Her research, which finally published in 2017, indicated that IPV survivors who’d suffered from TBIs had “poorer cognitive performance” when it came to both memory and learning.

Today, Valera still describes her field of research as “very small.” It includes the Barrow Neurological Institute’s Domestic Violence Traumatic Brain Injury Program in Arizona, the “first of its kind in the nation” when it launched in 2012. The Ohio Domestic Violence Network has a similar program, and researchers at Rutgers and The University of British Columbia also study IPV-related head trauma.

In British Columbia, Paul Van Donkelaar had been studying sports-related concussions among young hockey and football players for close to two decades when he met shelter director Mason on Tinder in 2015. A few months into their relationship, Mason read an Los Angeles Times op-ed linking TBIs and domestic violence. “I had never heard of this connection before,” she says. “I forwarded that article to Paul and I said, ‘What are you doing studying football players? We need to study women.’”

Van Donkelaar pivoted his studies, and the pair started SOAR, Supporting Survivors of Abuse and Brain Injury through Research. Through their work, Van Donkelaar says he’s found that IPV survivors “had more, and more severe, symptoms than the young athletes” he’d studied. Furthermore, he was testing the IPV survivors about a year after their most recent brain injury, while he’d been looking at young athletes within three days of theirs. That meant IPV survivors’ TBI symptoms were “chronic in nature,” he says. Like in Valera’s studies, he found cognitive functioning in these survivors had been negatively affected.

These types of long-term symptoms present unique challenges to IPV survivors. Those confronting abusive current or ex-partners in court, for example, may have trouble preparing their cases if they’re suffering TBI-related memory loss or impaired cognition — on top of dealing with the depression and anxiety that can also arise from TBIs.

The historic lack of information about IPV-related TBIs further deprives survivors not only of much needed services that can help address their symptoms, but also the comfort of a diagnosis. “Realizing that brain injury…explains some of the challenges they’re facing gives [survivors] empowerment,” says Van Donkelaar. “It’s not them being stupid or crazy. It’s actually a physical injury.”

That’s exactly how Freya felt when she first learned about TBIs. She “breathed a sigh of relief,” she says, knowing she wasn’t “crazy” or “suffering from dementia.”

Mason described one instance in which an IPV survivor who took a concussion awareness course was able to educate her doctor — who’d previously brushed off the survivor’s health concerns — about TBIs. More information about these injuries can also inform frontline IPV workers’ practices. Mason says she advises shelter workers to “dim the lights in a room” while meeting with TBI survivors who may experience light sensitivity, or to work closely and patiently with survivors as they may struggle to fill out forms like job and housing applications.

***

Valera says interest in IPV-related TBI research has grown over the past year. With many sporting events suspended during the pandemic, researchers needed a new TBI-prone population to study. Meanwhile, the pandemic drew more awareness to IPV survivors.

These researchers, however, continue to encounter obstacles. Recruiting study participants can be tricky, says Mason, because of the “shame and stigma” that surrounds IPV. To address this, SOAR’s research coordinator also serves as a counselor in a women’s shelter, which helps them gain potential study participants’ trust.

Meanwhile, the general public still doesn’t know much about TBIs and IPV. People know all about TBIs in football, says Valera, because of the media attention it gets, including in Hollywood films. She wants the message to get out that “women are sustaining these brain injuries all the time,” beginning with education about IPV in schools.

Freya has been part of the ongoing public education effort. She’s spoken at PINK Concussions events, which aim to spread the word about women who get TBIs from sports, military service, and violence. “It turns out to be a very, very powerful thing to sit in front of all these scholars and researchers, and people who truly can make a difference, and tell your story,” she says, “and have them look at you like, ‘Wow, thank you. You’ve just given me an idea.’”

*Freya is using a pseudonym used for privacy and protection from her ex-husband.