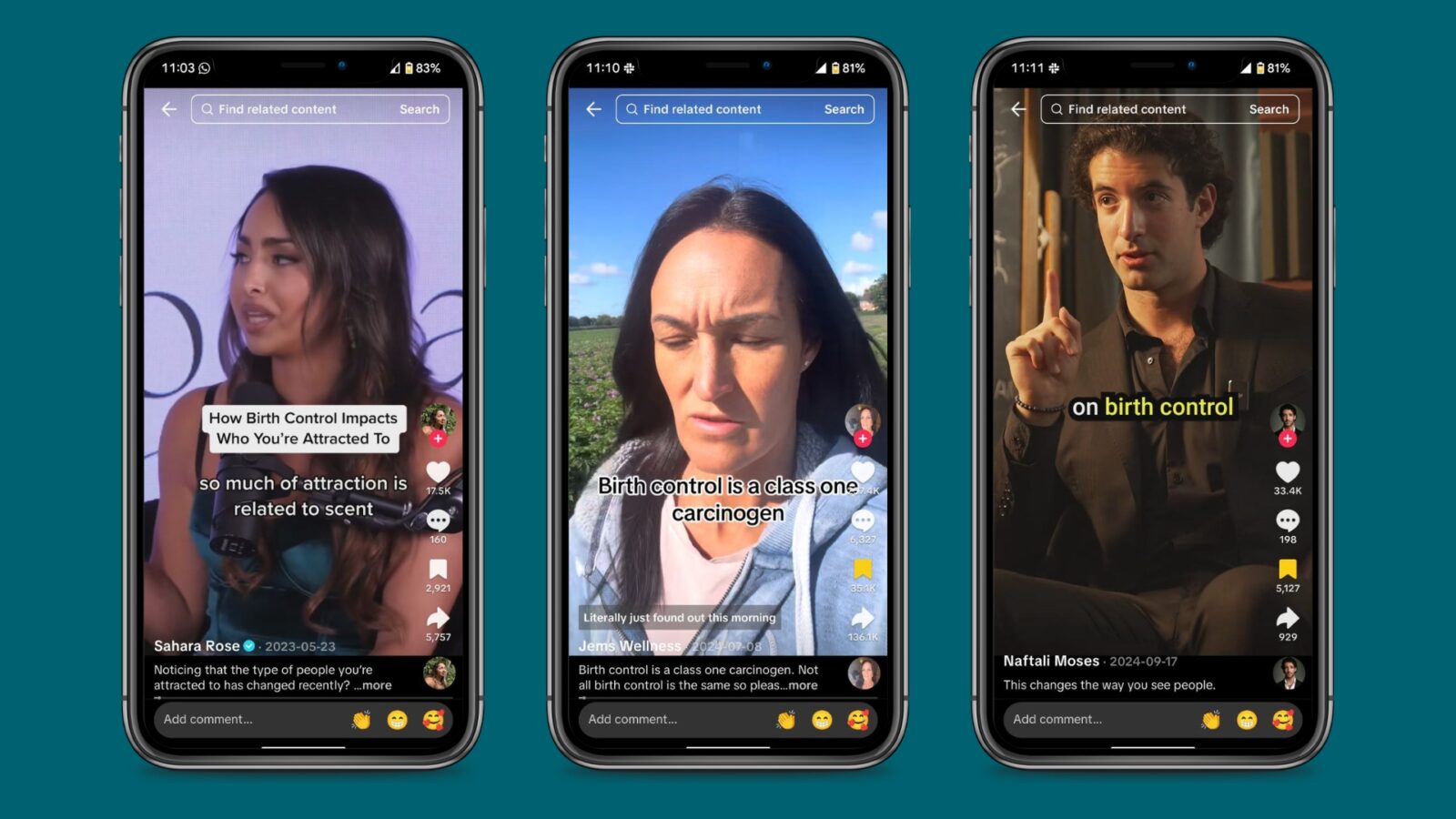

While out on an idyllic countryside walk, @JemsWellness, a TikToker who describes herself as a “biohacking wife,” casually suggests that her followers “rethink” taking the contraceptive pill, telling them she’s just learned that it’s “been classified as a class one carcinogen by the World Health Organization (WHO).”

She first defines the term (“there is enough evidence to conclude that it can cause cancer”) before telling viewers to either seek out alternative forms of contraception or start “looking at diet and lifestyle,” if they take the pill for reasons other than pregnancy prevention.

While it is true that the pill has been listed by the WHO as a carcinogen, and the video’s caption wisely recommends that people “carefully evaluate contraceptive options before use,” what Jems Wellness fails to mention is that the group one listing is not new, doesn’t apply to all types of birth control pills and says nothing about the risk level. Despite the missing context, the video goes viral. It has more than three million views and 250,000 likes, with the hashtags #BirthControlPill and #contraception amplifying the post beyond the British influencer’s 12,000 followers.

Jems Wellness’ content is a mixture of supplement tips (for magnesium, lion’s mane, wild carrot seed oil — all of which can be easily bought via a link in her bio) and grave warnings about teenagers on the pill being “130% more likely to suffer depression.” But you don’t have to look far to find even more eyebrow-raising claims.

On TikTok, “modern renaissance woman” Sahara Rose Ketabi speaks of “the divorce pill,” claiming that oral contraception changes women’s attraction to their partners. Also based in Los Angeles, like Ketabi, is Naftali Moses who along with fitness advice opines regularly on gender roles and relationships, telling women “men will treat you differently when you’re not on birth control.” Variations of these theories are repeated by numerous smaller accounts on TikTok and Instagram.

I have been unable to find Jems Wellness’ real name and none of the creators responded to my multiple requests for comment.

Videos like this that blend personal anecdotes, pseudo-science or other non-Western knowledge systems such as Ayurveda and lifestyle advice are where users looking for health information often end up. Self-styled hormone coaches or spiritual influencers are racking up millions of views to posts that claim – with little or no evidence – that the pill causes long-term infertility or “inhibits your natural femininity.”

A recent analysis, by academics at La Trobe University in Australia, of the top five hashtags related to contraception on TikTok – with 4.85 billion combined views – revealed that only 1 in 10 posts were by health professionals. Overall, the researchers wrote, content is of “poor reliability and quality, indicating a prominent presence of contraceptive health misinformation.”

As for the platforms, while TikTok has policies against medical misinformation and has in the past taken down content related to the pill, similar videos remain readily available.

Sexual health experts in the UK fear that this increasingly prevalent misinformation, along with fears about side effects, are leading to falling numbers of people taking the pill and growing mistrust of healthcare professionals.

Acknowledging genuine side effects

Dr. Frances Yarlett, medical director at The Lowdown and GP with the NHS, addresses some of the most common myths about side effects of the pill.

- Weight gain: While the pill can cause fluid retention and increased appetite, the pill itself is not leading to weight gain.

- Long-term infertility: Infertility after getting off the pill is another common worry, but Yarlett says there is “absolutely no evidence that the pill harms fertility” with most people’s cycles returning within three months of stopping the pill. “If someone struggles to conceive, it’s usually because of an underlying condition like PCOS or endometriosis, which the pill may have been treating, not causing,” she added. And don’t forget that about half of those couples with fertility issues actually have male factors involved.

- Cancer risks: There is a small increased risk of breast cancer and cervical cancer. The risk for breast cancer goes back to normal within 10 years of stopping the pill, Yarlett says, and the risk of cervical cancer is not caused by the pill itself but by the HPV virus, which may be more difficult to clear when on the pill. This is why cervical screening is so important.

What often gets missed, Yarlett stresses, are the protective effects against bowel, womb, and ovarian cancers — a study looking at 221,000 women in the U.K. published in April showed the pill reduced ovarian cancer rates by 26% compared to those who had never taken the pill. “That’s huge, and nobody talks about it,” says Yarlett.

For Amelia, whose name has been changed to protect her privacy, social media only contributed to the confusion she was feeling as she tried to make sense of the migraines and mood swings that started after she was prescribed the pill at 19 to manage heavy, irregular bleeding. “You’d see one person saying the pill ruined their life, another saying it was amazing,” said the 33-year-old based in Glasgow. “I couldn’t find reliable data. I felt like I didn’t know who to trust.”

She went to multiple doctors about her side effects, and they all just put her on a different pill. A decade after starting the contraceptive, she decided to stop.

While side effects of hormonal contraception are well documented – common ones include headaches, breast tenderness and mood changes, while more serious complications like blood clots are rare – online content often magnifies negative experiences.

“There are certainly some women who feel very emotional, have lots of mood swings, and can get irritable, anxious or depressed,” said Sheffield-based Dr. Frances Yarlett, medical director at women’s health research platform The Lowdown and a GP working in the National Health Service. A landmark 2018 Danish study of more than one million women found that in the first few months of pill use, the likelihood of being diagnosed with depression rose 1.8 times, while suicide attempts or suicides roughly doubled.

Yarlett cautioned that mental health changes may not be the result of pill usage, saying that if a patient experiencing depression after being on the pill for a while, “when you dig deeper you realise they’ve had lots of other things going on in their life, and that is probably the cause of the change in their mental health rather than the pill.” However, if within a few weeks of starting on the pill a patient is, as Yarlett put it, “drastically different, even getting suicidal thoughts,” it’s time for a rethink: “I would never want a woman to continue so please reach out to your healthcare professional and discuss a different option.”

Marika, a 46-year-old in the coastal city of Brighton asked that her real name not be used due to the sensitive nature of her experience. She started taking the contraceptive pill in 2017, and within three months said she went from feeling fine to having suicidal thoughts. “I felt completely worthless,” she said.

One particularly difficult day, as Marika sat at her desk in tears, she thought about ending her life. She confided in a friend who advised her to stop taking the pill. Online, she found forums and social media posts filled with similar accounts. “I was horrified this was happening to so many,” Marika said, telling me her depression subsided after coming off the pill. She has since sworn off hormonal contraception entirely.

Stories like Amelia’s and Marika’s don’t prove that the pill is bad for everyone. But they help explain why misinformation on social media lands so effectively as influencers amplify individual experiences, cherrypick scientific data and research in order to provide generalised advice that aligns with their worldview – and, often, their commercial interests.

Compounding the problem is what researchers from Sheffield University call the “nocebo effect” where a heightened expectation that the pill will have side effects ends up being “self-fulfilling.”

Informing and protecting young people

Grace Green, a Manchester-based education specialist for sexual health charity Brook, said she regularly hears myths in classrooms that can be traced back to TikTok – sometimes lifted almost word-for-word from US influencers.

Explaining why the teenagers she meets are so susceptible, Green said: “Sometimes young people who’ve had a negative experience with the pill get lost in the middle. If their concerns aren’t properly explored by the adults in their lives, these myths will resonate more strongly with their anxieties.”

“Young people aren’t stupid,” Green added. “They’re using social media to try to make sense of their bodies because they don’t feel they’re getting enough from doctors or schools.” Ignoring their concerns, she warned, will just drive them deeper into an algorithm that rewards alarmist content.

Recognising the risks, some educators and nonprofit organisations are trying to address the need for reliable, trustworthy, accessible information . Brook runs school workshops to address myths directly while The Lowdown offers tools and user reviews of contraceptive methods so visitors to the platform can make informed decisions. Brook has also launched social campaigns that mirror the engaging formats influencers use, responding to common claims with myth-busting FAQs and videos.

There are policy efforts too. The Online Safety Act which came into effect earlier this year recognises that “the most harmful illegal online content disproportionately affects women and girls.” However, a year ago, campaigners noted that health misinformation was not specifically named in the Act.

Since coming into force, members of parliament have warned that the OSA is “unable to tackle the spread of misinformation and cannot keep users safe online.” This is in large part because of the lack of transparency about how recommendation algorithms work and also because the law takes no action against what’s been described as “awful but lawful” content.

The UK government has said it is trying to balance “addressing the greatest risks of harm to users, whilst protecting freedom of expression,” but in the shadows lurks the possibility that the Online Safety Act might still be torpedoed by external forces: a Trump administration opposed to the regulation of US tech companies.

Editor’s note: This story talks about suicide. If you’re looking for help, visit the International Association for Suicide Prevention’s dedicated site to find a helpline near you.

This reporting was supported by MSI Reproductive Choices. Read our editorial independence policy here.