On Mother’s Day in 1974, a group of women headed to New York’s Prospect Park with a stack of flyers and pressed them into caregivers’ hands.

“All women are unwaged workers,” the flyers read. “We work from morning to night, but at the end of the week, we have no money to show for it…We want wages for housework!”

Their call to recognize and compensate unpaid domestic labor — work largely done by women – was radical. But it struck a chord. In just a few short years, the movement quickly took hold and spread from Europe across America, Africa and the Caribbean.

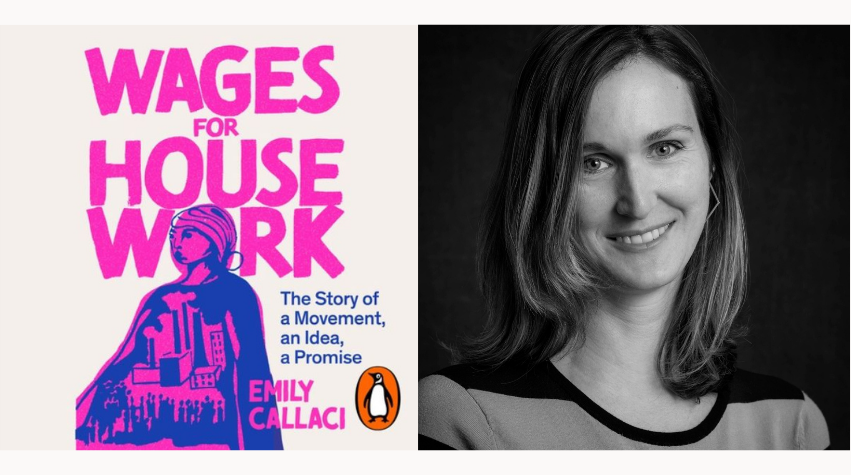

A new book, Wages for Housework, traces the history and impact of this polarizing but influential campaign, which feels as relevant as ever. Over 50 years later, women continue to do more than three-quarters of the world’s care work, contributing $10.8 trillion to the global economy annually — more than three times the size of the tech industry.

Writer and historian Emily Callaci started working on the book shortly after giving birth to her first child, a period typically filled with endless chores. The significance was not lost on her.

“I don’t think anything could have prepared me for the intensity of early motherhood — the ecstatic joy, the exhaustion, the boredom, the physical discomfort — and the absolute relentlessness of the work,” she says.

“I wanted to understand why so much of the most important work is invisible.”

She traces the movement’s history through five key women. From founder Selma James, an American factory worker who ran the campaign from her apartment in London to Wilmette Brown, a lesbian, poet and former Black Panther who launched the Black Women for Wages for Housework arm in New York, it was both international and intersectional.

At its heart, they argued capitalism could not function without housework — when an employer hired a worker, they typically didn’t just get one worker, they got two. Part of the reason why the campaign was so jarring was because it demanded compensation for something women were expected to provide out of love (and for free), writes Callaci.

As one Wages for Housework slogan summed up: They say it is love. We say it is unwaged work.

There were tensions, too. For some, the movement was about literally paying women. Others saw it more as a revolutionary struggle – a way to remake the world under capitalism. Amid tactical differences, the movement eventually fizzled out.

But its impact was significant. The women in Callaci’s book have inspired universal basic income campaigns, prison abolitionists and organizers of domestic workers who fought for – and won – new international labor standards.

If women were paid a wage for their vastly disproportionate contribution in unpaid care, they’d have a lot more power, says Callaci.

But she points out the movement demands wages for housework – not housewives. Historically this has largely been done by women – and disproportionately women of color – but these ideas are relevant to everyone. She asks us to imagine a world that compensates for the work of caring for people as much as production and consumption of commodities.

Her students already question the constant demand for productivity more than her generation ever did, she says. What use, for instance, is the so-called American Dream – a 40-hour work week and nuclear family home ownership – when you’ve grown up with a planet on fire?

“If my generation of feminists learned that career success would set us free, many of my students are more likely to echo what [American journalist] Sarah Jaffe has said: ‘work won’t love you back!’”

Still, housework is (sadly) unavoidable. How can we wash dishes without cursing capitalism and everyone in sight?

Callaci thinks about what she shares with others doing this kind of labor – those caring for elderly family members or underpaid workers keeping our public spaces clean.

“Much of the time, doing the dishes just sucks,” she says. “But sometimes, I can see these daily maintenance tasks as part of the bigger picture of valuable, unrecognized work, and I find that exciting.”