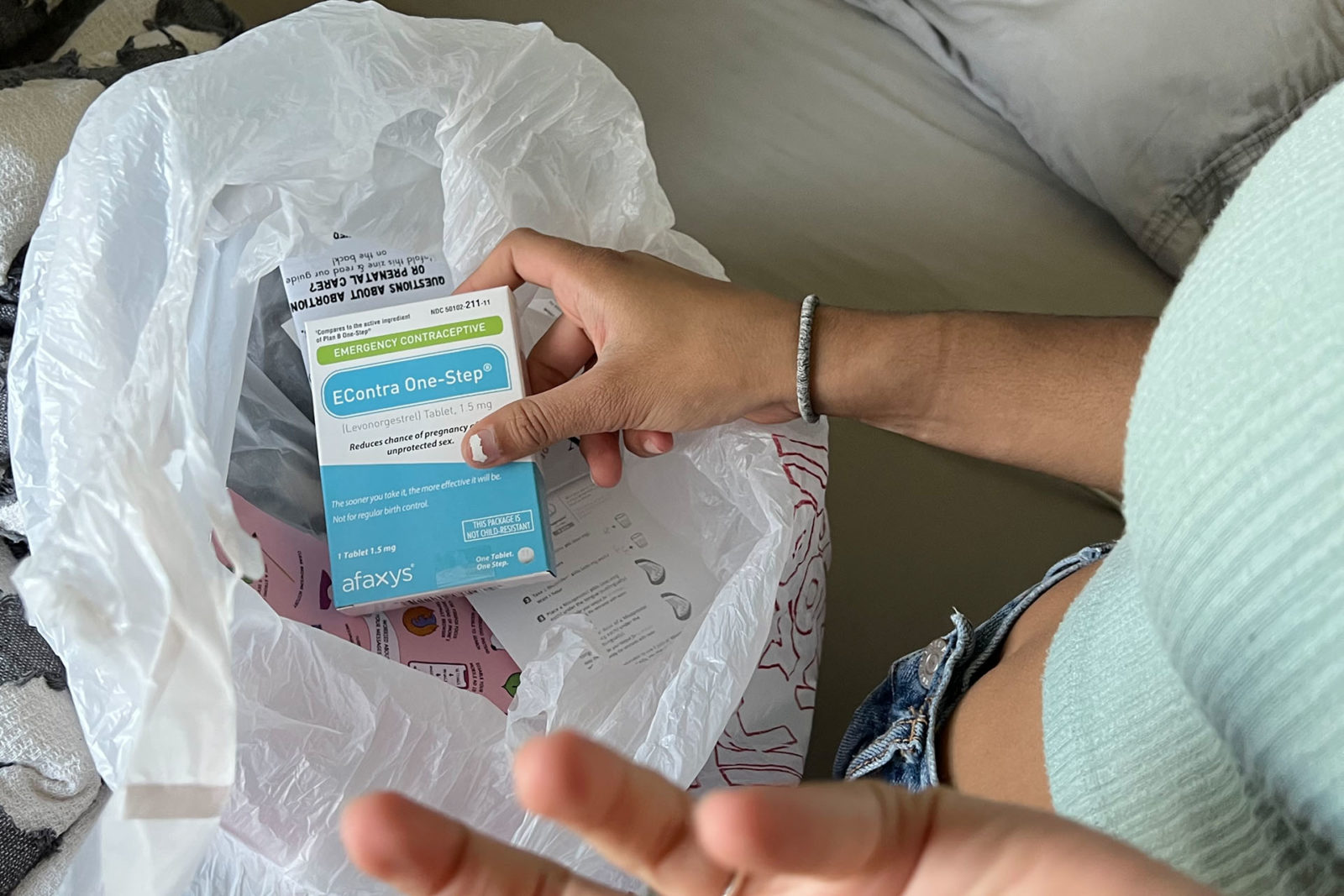

AUSTIN—Nikita Kakkad is on her hands and knees, grabbing packs of condoms from a cardboard box underneath her bed, pregnancy tests and pamphlets from another. She divvies them up between a dozen or so plastic grocery bags, adds two boxes of Plan B — the most common “morning-after pill” — and then ties them up and stuffs them in her tote bag.

“Repro kits,” she calls them.

Kakkad is, technically, a 19-year-old rising junior majoring in biomedical engineering in her home state of Texas — a state where reproductive healthcare access has been on the chopping block for most of her life. On this Thursday afternoon in May, she’s also one of the dozens of young people throughout the country who serve as roving dispensaries of reproductive health products for those with shrinking options.

“You’re making a difference – for real,” one person texted Kakkad after receiving a delivery. Another wrote: “Everyone forgets how necessary all of it is until they need help.”

Just weeks before Kakkad’s sorting and bagging, a leaked draft decision from the U.S. Supreme Court made clear that a majority of justices were considering striking down the constitutional right to choose an abortion. The morning after the leak was first reported, Kakkad’s kit-request volume spiked: More than 70 students reached out wanting Plan B over the next two days. On Friday, the court made it official, voting 6–3 to overturn the 1973 landmark case of Roe v. Wade.

Kakkad is one of dozens of current and former students — Parteek in Northern California, Lauren in Chicago, Jasmine in South Carolina — in a nationwide peer-to-peer network known as Emergency Contraception for Every Campus (EC4EC) that distributes Plan B and other reproductive health products on 25 university campuses. With the end of Roe v. Wade in sight, these volunteers are redoubling their efforts to keep people of birthing age stocked up on products they believe are indispensable to their health and autonomy.

The work takes on a special urgency for student volunteers in the Deep South, where unintended and teen pregnancies are higher than anywhere else, but abortion options are quickly disappearing. These are the same states where reproductive health resources, such as sex education and birth control, have never been robust.

Experts and physicians also say the landscape is cluttered with too much disinformation and misinformation about different reproductive health products: Is Plan B effective? (Relatively.) Does it work for everyone? (No.) Are there more effective methods to prevent an unintended pregnancy? (Yes, but they require a prescription or in-person doctor visit.)

“I remember in high school just constantly feeling scared and like I had no idea what I was doing when it came to having safe sex,” Kakkad said. “I hope each time I deliver a kit, it helps people feel like they’re not alone.”

With tote bag in tow, Kakkad takes a 20 minute walk across the sprawling University of Texas campus and throws her wavy black hair into a bun before cooling off in earnest in the sterile, air conditioned hallways of a classroom building. Here, she finds the drop off point for the bulk delivery of the repro kits: a room in the sociology department littered with reproductive rights stickers and dog-eared data analysis textbooks. She stashes the kits underneath the desk in a waiting Trader Joe’s paper bag.

Earlier that morning, she’d gotten a ping from an individual customer at a nearby apartment complex.

“Left the kit by your door!” Kakkad texted. The exchange — free to the customer — was done in under 30 minutes, proving that Amazon isn’t the only service capable of same day delivery. But for Kakkad and other campus volunteers across the country it takes a daily miracle of logistics and gumption to pull it off.

***

The network was created in 2020 under the national non-profit American Society for Emergency Contraception that helps students set up hotlines and provides as much Plan B stock as they need. The group comprises reproductive health providers, researchers, attorneys and advocates that promote increased access to emergency contraception. Though the group spans decades in the field, their new EC4EC project works on a small budget — launched with a $90,000 philanthropic grant and individual donations to cover $1,000 yearly stipends to student volunteers, supplies and shipping. The Plan B doses — EC4EC has sent out about 600 over the past two school years — are donated from the drug maker.

Each campus uses its own system for communicating with and delivering to customers. Some, like Kakkad, use Google forms, promoted through Instagram, to collect bare-bone details from students requesting a kit — first name, phone number and address where they want the kit delivered. For added anonymity, students can also opt to pick up kits at a rotating campus pick-up spot, like the one at UT-Austin’s sociology department, which updates on the form users fill out. Others use a text hotline or partner with local reproductive service providers that get requests. The products are always free to the recipients.

This work, Kakkad said, becomes even more essential with the Supreme Court’s court decision to overturn Roe. The fear, she said, is that there are even more profound changes to come.

“It’s not stopping here. [Lawmakers] are going to take abortion away, then they’re gonna take IUDs away and they’re gonna take Plan B away. Then they’re going to take birth control away,” Kakkad said, firing off recent news articles about proposed bills to ban contraceptives. “You can’t believe in precedent anymore when it comes to stuff like this….Where does the line end? I don’t think people realize how drastic it could get.”

Kakkad’s advice: “We have to be even more proactive about getting long-term contraception.”

But which one?

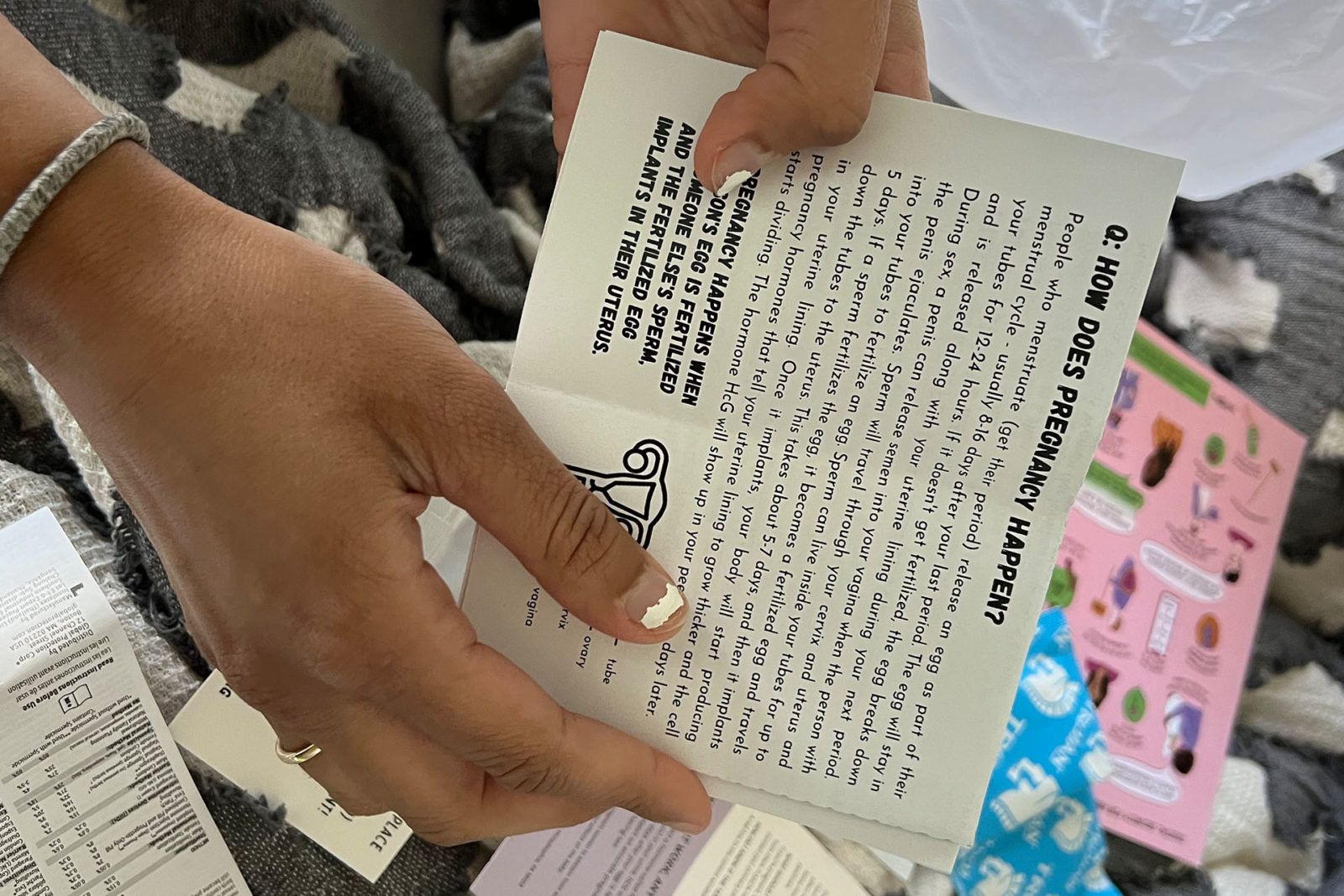

Though IUDs are the most effective contraceptive, Plan B is still a powerful intervention to prevent pregnancy. Approved by the FDA in 1999, Plan B delays ovulation, averting potential fertilization, after sex. Since 2014 it’s been over-the-counter without age restrictions — and use has skyrocketed. Nearly a quarter of sexually active women of reproductive age used the morning-after pill in 2019, up from 11% in 2008 and 4% in 2002.

Despite its proliferation, barriers to access persist. It costs anywhere from $45 to $68, depending on the brand. And sometimes, even if students have the cash and are ready to buy it, it’s just not possible to obtain.

Nearly half of campus pharmacies report not stocking Plan B on the shelves, despite its over-the-counter status. And campus health centers aren’t always accessible — either located far from the campus-center, only open 9-5, or otherwise unreliable.

That’s why some universities, including University of California, Davis and Purdue University in Indiana, have stocked some on-campus vending machines with emergency contraceptive products.

“We want to increase access to care in any way we can,” said Michelle Szabo, the Purdue graduate student in charge of the project told the campus newspaper.

Access to products and services aren’t the only challenge for those seeking reproductive health care. Misinformation swirls around Plan B. In reality, Plan B, like hormonal daily birth control pills, prevents ovulation. But outdated information on the packaging label incorrectly claims it could prevent “attachment of a fertilized egg to the uterus.” That inaccurate language has been used as rationale to ban Plan B by lawmakers who want to codify life as starting at fertilization. Anti-abortion groups have successfully blocked access to emergency contraceptives on some campuses using that argument.

Plan B is also not for everyone, experts warn. The pill needs to be taken as soon as possible after sex and loses efficacy over time. It also doesn’t work as well for people who weigh more than 165 lbs.

“Plan B is not the most effective [emergency contraceptive], it’s actually the least effective. But it’s the most available,” said Dr. Mimi Zieman, an OB-GYN in Atlanta and author of contraception textbooks.

There’s still at least a 96.9% likelihood that it’ll work, and she points out that barriers to more effective emergency contraceptives are often higher. Ella, another morning after pill that prevents pregnancy by blocking progesterone production, is more effective than Plan B, at 97.9%, but requires a prescription. Ella is also more effective for heavier folks and can work up to five days after sex.

Having a copper or hormonal IUD inserted soon after sex is the most effective emergency contraception, at 99.9%, but requires an in-person clinic visit, a co-pay and an invasive procedure. Only about 30% of college campuses report providing IUD services.

Experts say having more options readily available is the best way to intervene on unplanned pregnancies, and another reason why EC4EC is pushing for vending machines across the country. Kelly Cleland, executive director of the American Society for Emergency Contraception, has worked on reducing barriers to contraception her whole career. She’s hoping that daily birth control pills, as well as Ella, the morning-after pill that prevents pregnancy up to five days after sex, will be dispensed through vending machines if they’re available over the counter in the near future — especially as states limit access to abortion.

“Our goal is to make it as easy as possible for students to care for their own reproductive health needs,” Cleland said. “And so being able to have a vending machine in a fairly accessible place with 24/7 access, in a building that’s easy to get into is key.”

Cost is important, too, Cleland noted. When universities agree to stock Plan B, they can control the price. Boston University recently launched its emergency contraception vending machine with $8 Plan B. It’s places in the South that will likely soon ban abortion, such as Texas, which already has the nation’s lowest contraceptive use, that need the groundswell of support to expand contraceptive access, Cleland says — the same places that are most resistant.

Zieman, the OB-GYN in Atlanta, agrees. “If conservatives want to decrease abortion, there’s one way to do it,” she said, “and that’s access to contraception. Banning abortion doesn’t eliminate abortion, but it’s been well-proven in many, many, many studies that increasing access to contraception decreases abortion.”

***

Jasmine works with EC4EC in South Carolina, mailing out Plan B and other resources, such as condoms and pregnancy tests, throughout the state after launching the program while in grad school. She asked to be identified only by her first name for safety concerns.

South Carolina recently joined a growing list of states that allow pharmacists to prescribe daily birth control pills, nixing the need for a doctor’s office visit. Only North Carolina and Tennessee in the South have similar laws, despite the region being poised to ban abortion now that Roe v. Wade has been overturned.

Reproductive health advocates say the legislature’s move to reduce barriers to birth control is a step in the right direction, but it’s not enough.

“There’s so much healthcare that people in the South deserve that they don’t have access to whether that’s because of transportation issues or affordability or stigma,” Jasmine said. “All of these issues are connected.”

She launched an emergency contraception hotline called Palmetto Repro last year and hopes to continue it into next year while attending med school. Folks text in and she mails out a package the next day.

Like Kakkad, she has a stash of Plan B and other reproductive health resources at home. She charges $5 to pay for shipping, but covers the costs herself if someone can’t pay.

Jasmine loves the work, but as the sole Plan B distributor in the state, it takes a toll. “There’s not really any office hours and someone could text me at any time,” she said. And they do — texts come in at all hours of the day and night, and Jasmine jumps into go-mode when they do. “Relying on the mail, I’ve got to make sure that people have access to their products within an acceptable time.” When she travels out of town, she takes a few kits to have on hand and hunts down a post office, if needed.

Though anonymity is key to all EC4EC hotlines, working on this time-sensitive solo mission helps Jasmine connect to her home state in a way she didn’t expect.

“I can make an impact by assisting people that I walk past everyday, people that I went to college with, that I met at parties, that I see in traffic,” she said, “I never know who they truly are, but I do know that I’m helping them.”