It came as little surprise to Donna Malkentzos when she ended up with asthma and rhinitis — these were common early outcomes for 9/11 first responders like her. At least it was covered by the World Trade Center Health Program (WTCHP), the federal government program that monitors and treats 9/11-related health conditions. Then, in 2013, she was diagnosed with uterine cancer.

Malkentzos assumed she’d get the same medical care from the WTCHP. After all, she knew they treated most cancers. But the program’s administrators delivered bad news — they said her uterine cancer wasn’t related to 9/11 exposure. She had the only form of cancer that the program refuses to cover, a decision which affects thousands of women who were around Ground Zero in the days following the attacks on the World Trade Center.

Finally, this summer, Malkentzos thought she would get that coverage. The Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, which administers the program, agreed this past May to add the cancer to its list of covered conditions linked to 9/11 exposure. But this decision has still not been enacted, and Malkentzos and others with uterine cancer remain in limbo.

“If they didn’t approve prostate cancer right away, I’d think it’s just the government moving slowly. But it only moves slowly for women it seems,” says Malkentzos, who now lives in Cape May, New Jersey.

The CDC changed its mind after a decade of lobbying by health care advocates, researchers, and patients that was covered last year by The Fuller Project. The government’s original reasoning for not including uterine cancer is they didn’t have enough data linking the disease to 9/11 exposure. But health care researchers say this is because the data collection for the program systematically overlooked women, and skewed heavily from the start toward issues that are more likely to affect male first responders.

There were less than 10,000 women in the program’s original cohort of 62,171 first responders and “survivors” — people who lived, worked, or attended school around Ground Zero. Their information formed the basis of its screening process, and as a result there are only 26,125 women like Malkentzos today among WTCHP’s 114,775 members. They make up only 23% of patients even though they comprise roughly half the program’s eligible population of about 423,000 first responders and survivors.

Health care researchers say this bias continues to haunt the program. Aside from the delay in including uterine cancer, female first responders and survivors with other illnesses that usually primarily affect women, like autoimmune diseases, are also left without federal support.

This kind of gender bias in data collection and analysis is systemic in health and science, says Irene Aninye, chief science officer at the Society for Women’s Health Research.

“The people making the decisions to open and close the doors, they don’t have the data that they need,” Aninye says. “Women need to be included in more studies, but data also needs to be analyzed with a lens of recognizing that they are small in number. And that’s a different mindset.”

“You cannot analyze small numbers the way you analyze big numbers. If there are 10:1 men to women in this project, the lens that you use has to be different… you’re not going to see the overwhelming trends that you’ll see for men.”

Aninye says studies frequently suffer from “gender-blindness” — failing to disaggregate and analyze variables by sex to suss out differences between men and women. In the case of 9/11, only 11 out of more than 1,200 research articles on the topic collected by the CDC are centered on women. Seven of them focus on pregnancy.

A golden ticket, just out of reach

Malkentzos has had two recurrences of her cancer. Over the years, she has needed chemotherapy, radiation, and surgeries, none of which were covered by the government. Because it’s not covered by the health program, she’s also ineligible for up to $250,000 in federal victim compensation for people with 9/11-related cancer.

“My wife is more bothered by the cancer than me,” Malkentzos says, “I’m more mad about the fight to get it covered.”

Entry into the WTCHP is the golden ticket to get a 9/11-related illness covered and treated by the federal government — everything from asthma to PTSD to most cancers.

The health program has its own physicians, records, and insurance program. Once you’re in based on a 9/11-related illness, you’re in for life. All preventive care, disease treatments, and follow-ups are covered, and the data collected is recorded to help the feds understand the ongoing health ramifications from 9/11.

With data collection heavily slanted toward issues that affect men, survivors who became sick later with conditions that mostly affect women have had a harder time proving their illness is related to 9/11.

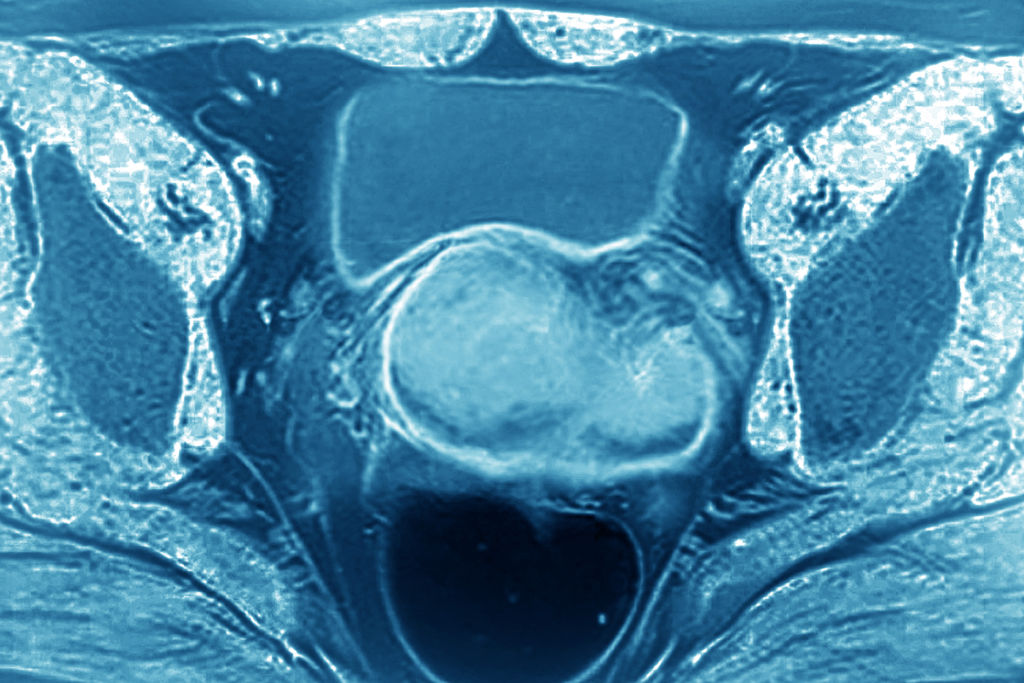

Uterine cancer is the main form of endometrial cancer, and the most common gynecological cancer, affecting about 3 percent of women. There’s no official tally of uterine cancer among the Ground Zero population because no agency has researched it. Attorneys and advocates who’ve kept track estimate at least 50 cases. Based on the number of female survivors and first responders and the prevalence of the cancer in the general population, there’s likely thousands of cases.

The lack of federal program data on women today mirrors gender-blindness issues in New York City’s surveys to collect information on survivors and first responders, which informed the screening for the very first WTCHP cohort. Out of five surveys sent out by the city, only one asked specifically about women aside from questions about pregnancy status — a 2011 survey that asked a few questions about their alcohol consumption and their periods.

Living with fear

“From the beginning, I never expected much would come out of it based on how we’ve been treated,” says Patricia Grande, 79, who worked in an office building at Ground Zero. “All the focus was on first responders, and that left out most women.”

Grande developed uterine cancer in 2011 and never received any help from the federal government. She wasn’t able to get into the WTCHP because the cancer wasn’t a covered condition and, unlike Malkentzos, she wasn’t a first responder.

In remission now for 10 years, Grande, who still lives in Manhattan, doesn’t go a day without fearing the cancer is back. The stress is made worse worrying about how she would pay for it.

“Once you’ve had cancer, especially under these conditions of being excluded, every pimple, every pain, every scratch is another form of cancer,” she says.

Meanwhile, external research was starting to pop up that backed her case. Multiple studies released between 2014 and 2017 established links between endocrine disrupting chemicals (EDCs) and cancer, including uterine cancer. EDCs include the asbestos, heavy metal, and gasoline combustion found in Ground Zero smoke and dust.

After multiple petitions, a CDC committee specifically created for 9/11 studies recommended in Nov. 2021 that the health program add uterine cancer based on scientific research. Public comments and peer reviews were solicited and submissions completed by June — all were in favor of adding it.

Yet uterine cancer patients are still waiting. Different departments within the Department of Health and Human Services, a federal agency, and the CDC need to sign off on the new rule, even though the latter is part of the former.

“The petition to add uterine cancer to the list of covered conditions was filed more than two years ago, yet a prolonged bureaucratic process, in which government agencies have missed deadline after deadline, has prevented women from receiving the healthcare they need and deserve,” says Rep. Mikie Sherrill, a Democrat from New Jersey, a state that’s home to many 9/11 survivors and first responders.

The Department of Health and Human Services did not respond to multiple requests for comment.

Stephanie Stephens, a CDC spokesperson, told The Fuller Project the agency is still in the process of reviewing public comments and peer reviews.

Malkentzos, the retired NYPD detective, says she’s less worried about her recurring cancer and more concerned about taking care of her family.

While the federal government drags its feet, NYPD, her former employer, did declare her uterine cancer to be 9/11 related. This would make her wife, Jackie, eligible for benefits if Malkentzos dies from it.

“When I go, I want to go because of the cancer,” she said. “That way at least Jackie will get my pension.”