They have educated half the Black doctors in the United States, almost all the Black judges and Vice President Kamala Harris. They are known for providing top-notch opportunities to generations of Black students since shortly after Reconstruction. But most public Historically Black Colleges and Universities (HBCUs) have been vastly underfunded.

For decades, when other universities refused to admit them, Black students attended HBCUs, which offered the best and often only opportunity for a higher education. Now, long after legal segregation ended, the 99 public and private institutions are modern meccas for Black scholars, athletes and artists. And many of them are growing.

Yet the 18 original HBCUs created by federal land grants have been underfunded by more than $12 billion since the 1990s. That is despite a federal law mandating that they receive state contributions equitable to those given to other land-grant schools.

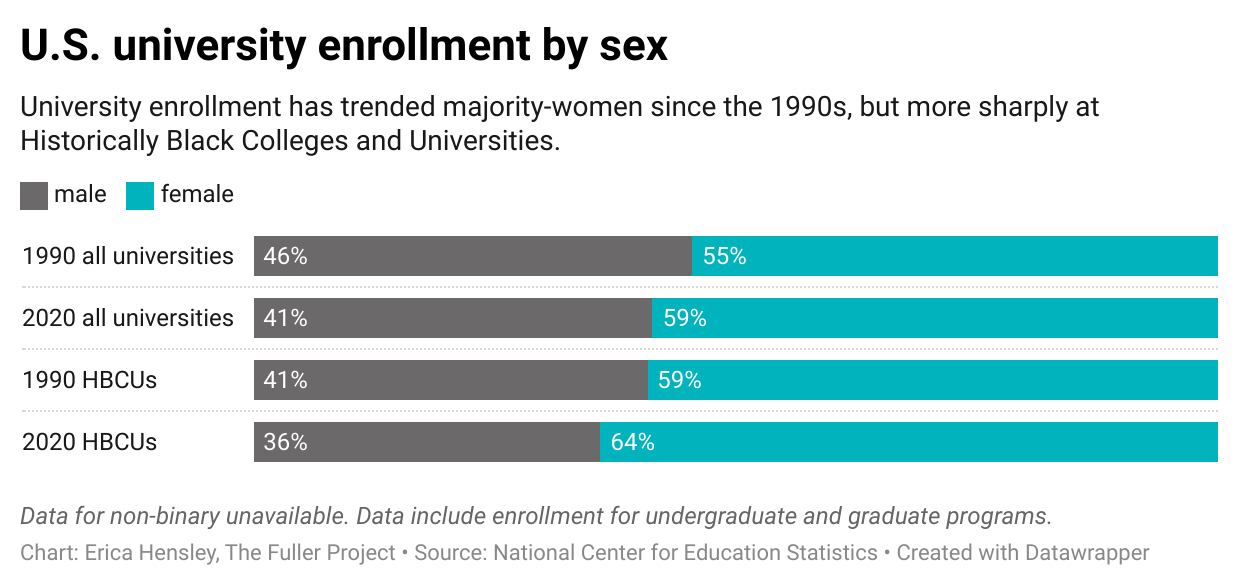

This disproportionately harms Black women, who greatly outnumber men at HBCUs. Since 1990, female students have represented the majority at American universities. But at HBCUs, the trend began much earlier: Black women have made up the majority of HBCU enrollment every year since 1976. In 2021, Black women earned 69% of all bachelor’s degrees granted by HBCUs; at all universities, women earned 58% of undergraduate degrees.

Their notable achievement has come at a price. Black women carry the most student loan debt of any demographic group, while also experiencing the highest pay gaps once they are in the workforce. In other words, they face a double whammy: higher student loans and lower salaries with which to pay them off.

Last year, the Biden administration sent letters to 16 governors reminding them of their obligation to provide HBCUs with additional finances and offering a plan to support debt repayment. Of all the states with land-grant HBCUs, only Ohio and Delaware fund them equitably.

The funding shortfalls mean that some HBCUs lack physical resources, like labs or housing, while others have had to cut back on grant and scholarship opportunities. Perhaps most problematic: overall, HBCUs spend just 57 % of what other schools spend on classroom learning, even though the majority of their undergraduates are first-generation students.

As Black History Month draws to an end, we sat down with Ashley Young, the education policy analyst at the Georgia Budget and Policy Institute, to talk about how underfunding HBCUs affects Black women. Georgia has ten HBCUs, the third most of any state, including the highly competitive Morehouse and Spelman Colleges.

As you note in your blog, HBCUs are modern beacons for Black resilience. Aside from being so important historically, how do they impact access to education, opportunity and, ultimately, the economy?

HBCUs have been such a linchpin for African Americans in the United States. When higher education was very out of reach for us in any other capacity, HBCUs have served as a pathway to Black joy and excellence — a way to build themselves up economically and have some sort of upward mobility, despite all of the other barriers around them. They have just been a place that as a Black person in this culture, we all feel at home.

The love and the energy around HBCUs is amazing — Black students are seeing the need for HBCUs and are gravitating a lot more towards them to really find affirming spaces. I’ve worked with some students who are second, third, fourth, and even fifth generation HBCU students. Many of their grandparents were involved in the Civil Rights Atlanta Student Movement — their ancestors went to college soon after slavery was abolished and these students carry those legacies behind them.

To me, the humanity part is more important than the economic draw — just providing spaces of belonging for African Americans in Georgia. But we do contribute to the state’s economic impact in a big way. HBCUs have always been a lasting beacon in our community that we want to continue to see flourish through responsible and equitable policy.

What does equitable policy look like for Black women who makeup two-thirds of graduates?

Black women holding the most student loan debt is a major crisis that needs attention. Even though the Biden administration just canceled some loan debt last week, which we love to see… it comes in waves. When we cancel student loan debt, we are helping Black women. When we don’t cancel student loan debt, as often or as much as it should be, we are disproportionately affecting Black women.

Thinking of that disproportionate share of the debt burden on Black women, how does that relate back to HBCU investment?

Statistically Black women must attain a bachelor’s degree just to earn as much as white men who have some college but no degree … we’re talking about 63 cents or so to a white man’s dollar. Black women borrowers are forced to borrow the highest amount of student loans to attend college and then suffer from wage discrimination during the repayment process. So we’re hit from the front and on the back end.

That is the case for Black women everywhere …The more that we invest in our HBCUs, the more we invest in Black women.